My Uncle Stuart died a few weeks ago. He was 70 years old and had been suffering from serious health issues, but not at a velocity that indicated we’d lose him that soon. It was, and will continue to be for some time, a shock.

Stuart was my Mom’s older brother, the oldest of five kids. His name is my middle name because of the special relationship Mom and Stu had; about the same 43 years ago when it was written on my birth certificate as it was just over a week ago, before his heart stopped. She would say, “We’re twins, but one year apart.”

My Mom was one of just a handful of people who even half-understood her brother, who was, and I’m searching for a more nuanced or artful way to say this, a pain in the ass. He was a huge man, handsome, and with an impressive beard and (frequently but not always) a short-cropped mohawk. He tucked flannel shirts into belted jeans or work pants, lest you get some kind of “biker” image.

His footwear of choice was a pair of fringed Minnetonka moccasins. Stuart was there for the early ’80s transition of “hard rock” to “heavy metal” (I vividly remember visiting his house as a young kid and being floored by some Iron Maiden albums next to his stereo). He was a loner and grumpy, incredibly hard-working, quick-smart, and funny as hell when you caught him in the right mood. There was no one like him.

When I was a little boy, going to my Grandma’s house for big family gatherings was something I loved, in large part because of Stu and my other three uncles (Ross, Dean, and Tyce). My brother and I were the only grandkids/nephews for years, so we got the lion’s share of attention, toys, and teasing. Stu would lie on the floor in the den after dinner, make me walk on his bad back, and call me “Beefasaurus”—I was a big kid—and pretend that I was crushing him. The uncles would give me models of WWII fighter planes for gifts, and then insist on “helping” me put them together. They’d all go out to the driveway to smoke cigarettes and crack jokes, and I’d tag along to listen, and pretend to understand and feel cool.

Always, there was a conversation about who was driving what. Cars and vans, and especially trucks were in the mix back then, and all are still painted into the background of every memory I can call to mind, from every era of my life. I as grew older that meant taking a lot of good-humored shit from Stuart, especially, about driving a string of Japanese and European cars. (Easier to make jokes about my Saab 9000 than my freshly minted socialist sensibilities, I suppose.)

And when I started writing about cars and driving everything new, it meant lots of download sessions with all of the uncles about what was interesting, what was bad, what was worth a damn. Showing up in the latest GM pickup (or an F-150 just to stir the pot) was frequently the move when I grabbed keys and headed to holiday gatherings. And inevitably, questions about whatever new thing I rolled up in transitioned to stories about the cars in the collective family history.

Quietly a GM Family

Like a lot of us, my relationships with vehicles and people are weirdly intertwined.

Growing up in Michigan and writing about cars for a living, I spent the better part of the last two decades talking trucks (especially Chevy trucks) with my uncles. So driving a Chevy back home to remember Stu felt right on every level. The new Silverado RST, weirdly appropriate in fully blacked-out trim, felt right for the occasion. The cars and car stories from the maternal side of my family—Michigan-born and raised, almost without exception—were assembled on a General Motors production line.

My Mom’s first car was a 1969 Camaro RS that she bought from Stu—well, Grandpa bought it for her and she paid him back. And while she occasionally strayed from the GM fold over the years, the hands-down-best car of my childhood was her 1984 Pontiac Fiero. (A car so beloved I actually owned it for a spell, despite knowing its considerable flaws.) For the last decade, she’s been back in modern Camaros as daily drivers.

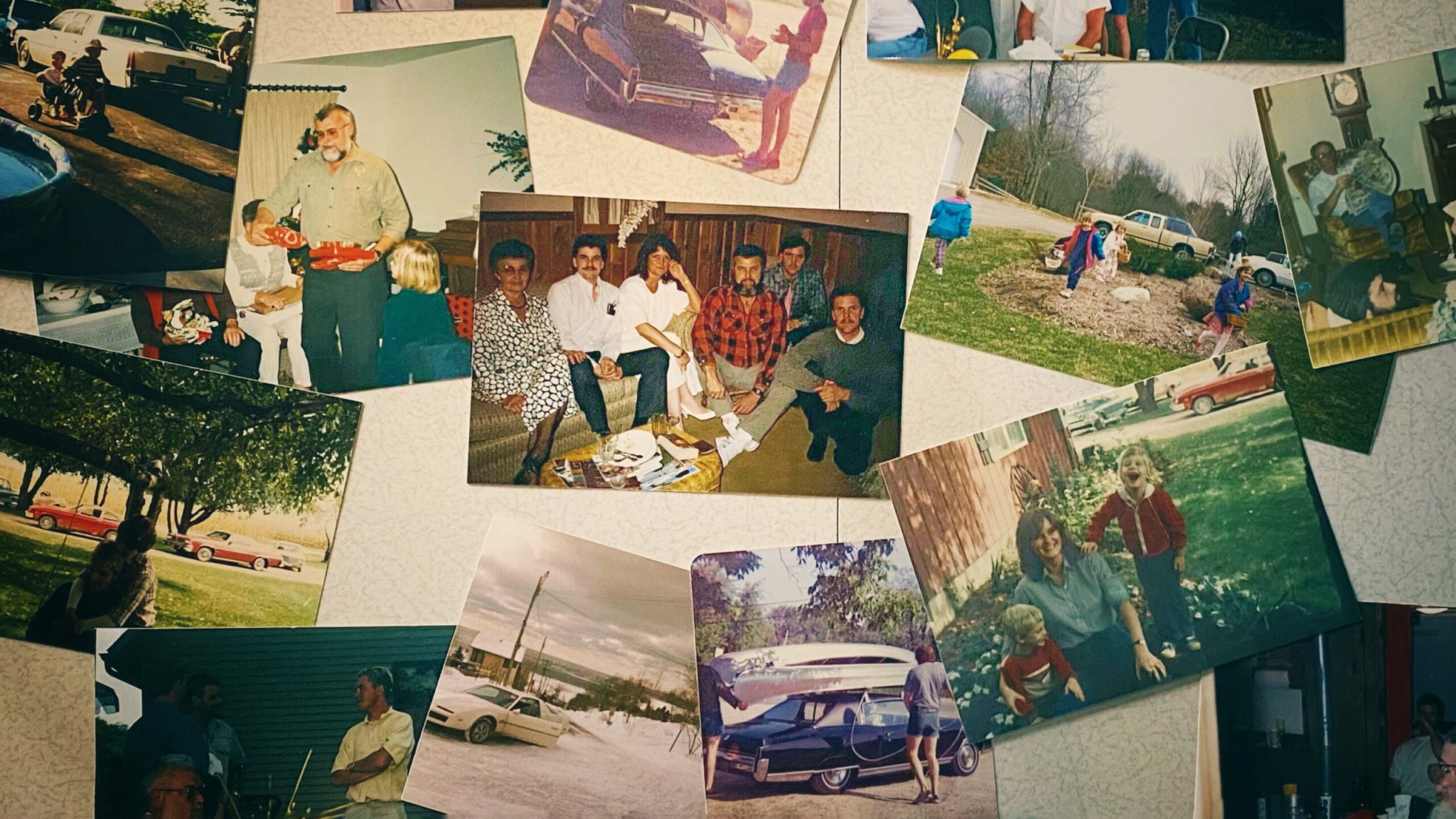

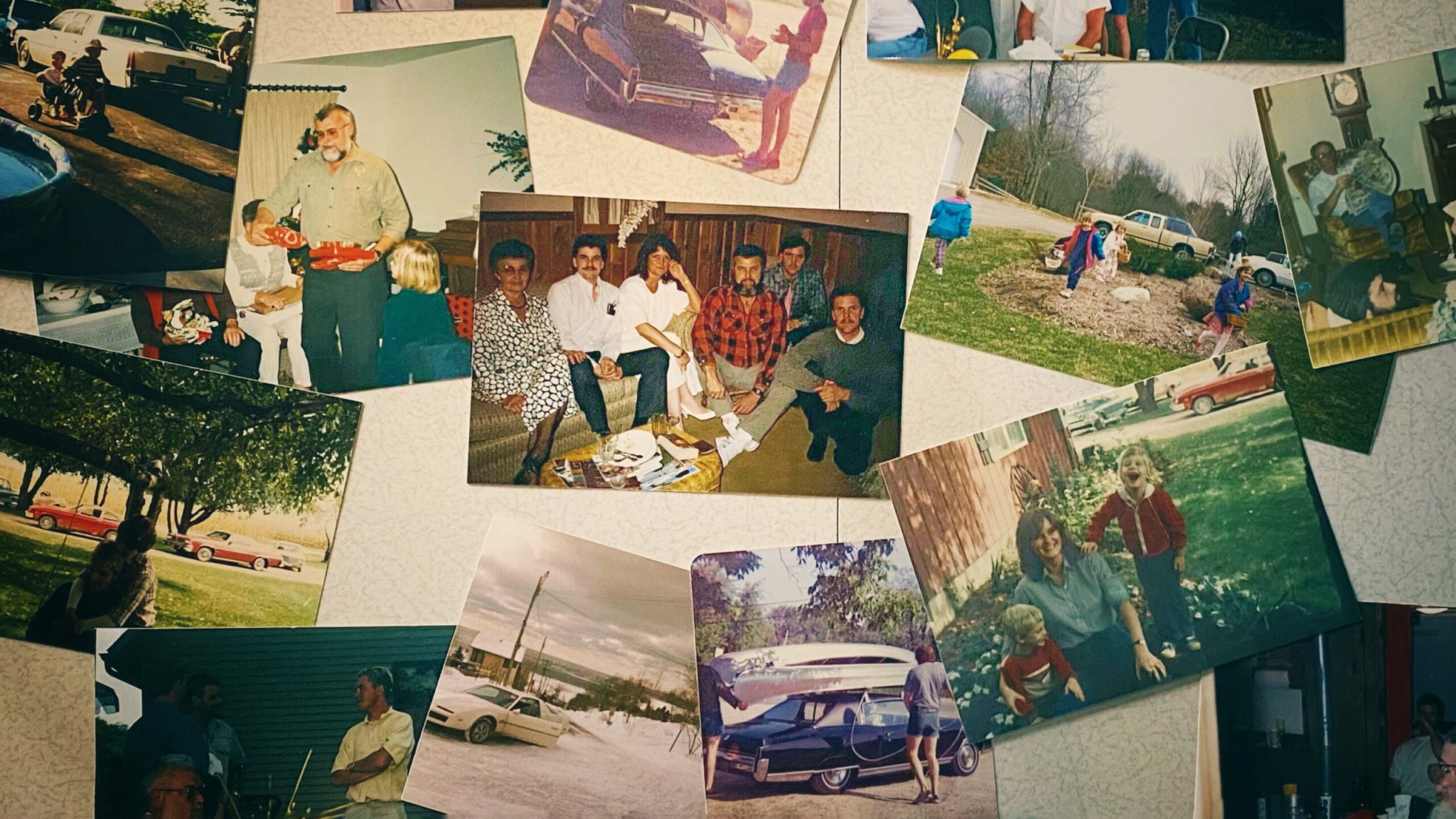

Over the years, family gatherings have been similarly populated with Chevy metal. Shuffling through old photo albums, I’ll recognize Corvairs, Chevy IIs and Novas, Monte Carlos, Impalas, and Vegas. At some point, sedans in the driveway turned to masses of minivans: GMC Safaris, Pontiac Trans Ports, and our family’s unkillable Chevy Lumina. A string of white Cadillac sedans was parked in my Grandma’s garage through the ’90s and early aughts (remind me to tell you the one about how she took her first CTS back to the dealer when she realized it wasn’t front-wheel drive), then a couple of Buicks, and then we pulled her license at 90 and she’s still pissed.

And I’m sure every generation of each Chevy and GMC pickup has been represented at one time or another. My all-time favorite truck is and forever will be a Chevy Square Body (that’s a third-gen GM C/K pickup, for the uninitiated). My Grandpa Adrian, who passed in 1986, drove a silver ’80 or ‘81 C100 that I remember so well I can close my eyes and smell the hot vinyl seats and whisper of cherry pipe tobacco.

The cars mattered. Stuart and my mom and their brothers took huge pride in owning them. But they didn’t matter in a bumper sticker kind of way. I grew up with a lot of people who would drive a Chevy the same way they’d wave an American flag. This was quieter. A family habit. The thing that is known to be “what we do.”

For Stuart, driving a Chevy was a way of life, to be sure. That Camaro he sold to my Mom was followed by a 1971 Monte Carlo in Tuxedo Black with a black vinyl wrapped roof and a cream leather interior. (This car is nigh onto legendary in my family—the jealously it inspired in Stu’s siblings almost palpable whenever they recall it—and yet the only photo we could dig up shows it being loaded with canoes for a trip to the river.) Many bow ties would follow.

His last Chevy was a late first-generation (I’m unsure of the model year) Colorado, red over black, with the uncelebrated 3.7-liter five-cylinder under the hood. A modest vehicle to say the least, but Stuart treated it like an heirloom. Another strong family trait (latent in me until my mid-30s) is a focus on car care that borders on the obsessive; I never saw Stu’s Colorado in any condition but spit-shine clean.

He was pretty proud of that truck. I remember him parking it next to my mother’s Camaro on a Sunday a million years ago, and telling me to “write a story about that” with a wheezy chuckle. (Two red Chevys in front of a barn in Michigan seemed like a hook, I guess.) His Colorado was the last thing we talked about—him loudly defending the merits of the five-banger, “I’ve had zero trouble with it!” as if that were an accolade—at my Grandma’s 90th birthday party.

In solitude, these snippets of conversation, those blurry memories and yellowed photos of backyards and driveways on summer days for decades, don’t mean much. We passed the time. We talked, in a landscape increasingly fraught with ideological differences, about the cars we had, and the car memories we have in common. Each story is small, any one car unimportant, but in the aggregate, they’re about everything we share.

For Me, It’s Complicated

Uncle Stu would have laughed at and loved the Silverado RST. Sixty-some grand for a pickup would’ve offended his sensibilities as an old Dutchman—we’re notoriously cheap. But the triple black spec, high-gloss wheels, and the menacing rumble at idle from the 6.2-liter V8 would have given us plenty to chew through.

But being back behind the wheel of a new Silverado, thinking and writing about family, felt especially loaded this week. Until two months ago I was employed by ad agency Campbell Ewald, GM as my main client, and editing the Chevy owners magazine, New Roads, was my biggest responsibility.

As editor of New Roads magazine, I had a lot of reason to think about families not unlike my own, but evangelistic about the brand in a way that took me by surprise. I read letters from owners with vast and often obscure collections of vintage models; heard from families generations deep in Chevy truck ownership; weirdly saw innumerable pictures of cars and trucks lined up in driveways. People loved to get all the cars together for the automotive version of an awkward family photo. (Pro tip: a magazine editor is extremely unlikely to run your tiny photo of six trucks lined up in the driveway guys, please stop trying to make this a thing.)

Goofy or not, the stories of cars are the stories of people. As you’d expect from a 110-year-old American company with millions and millions of cars sold, the stories I heard (and sometimes retold) were as varied and complicated as the country itself. Sometimes touching, sometimes reverent, sometimes jingoistic, sometimes actually hateful. Rarely did reality align perfectly with whatever the current corporate narrative was. And rarely did our magazine correctly reflect the cohort of owners it was mailed to. Life and truck ownership are messy that way.

Still, it was clear the cars mattered. People moved their families across the country, brought babies home from the hospital, brought their kids to college, made fortunes, scraped through hard times, buried loved ones, all with a Chevrolet in the frame.

Most of us don’t own very many cars throughout our lives, so their entries and exits make good bookmarks. Time machines in yellow bow ties.

I don’t know if Stuart would’ve ever said it out loud, but I’m sure he understood that magic. That each Chevy he owned, each family vehicle he remembered, bundled emotion and memory in mechanical form. That driving a truck can reflexively feel like family.

Got a tip? Email tips@thedrive.com.