Even if you’ve continued working through this seemingly never-ending pandemic, there’s a great chance you’ve found yourself with more free time since there’s hardly anywhere to go outside of your home. Boston-based data scientist Devin Gaffney unfortunately found himself in an underemployed situation but decided to make the most of his newfound spare time. He built an exceptionally accurate data modeling tool, specifically for the popular car auction site, Bring a Trailer.

Gaffney explained to The Drive that he started the project in mid-April after looking at a listing for a 1967 MGB GT, which was to replace his 1986 Saab 900. While discussing the auction with a friend, he found out that another had recently sold for much less, which got him thinking of ways to get the most information and score the best deal. He got to work and despite his penchant for cars that break, his models do not.

To start, Gaffney wrote a data collection system in a programming language called Ruby that scours Bring a Trailer auctions and dumps the information—including auction times, bids, and comments—into a database. He uses Ruby to then call out to another programming language named Python to build the actual models.

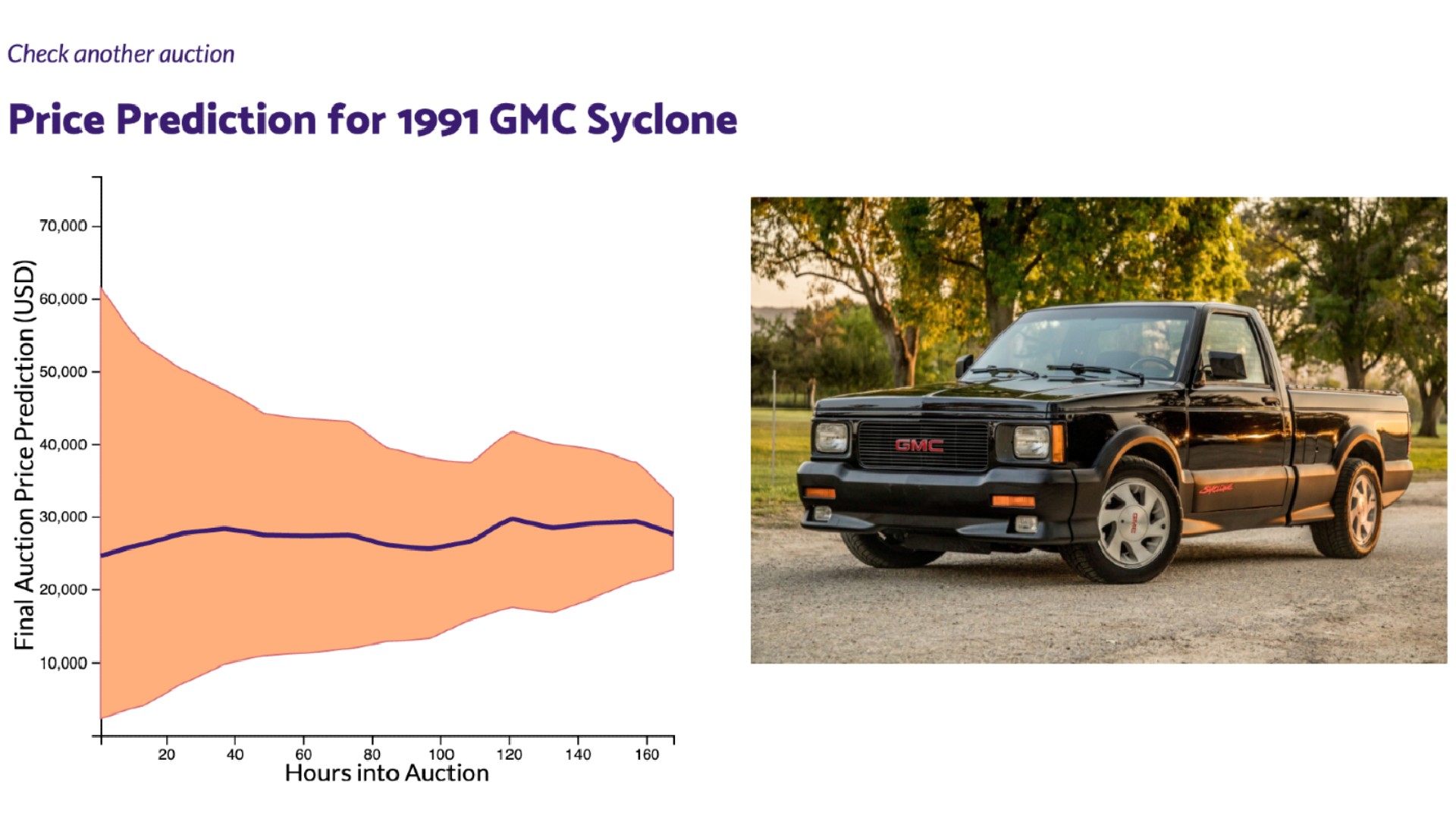

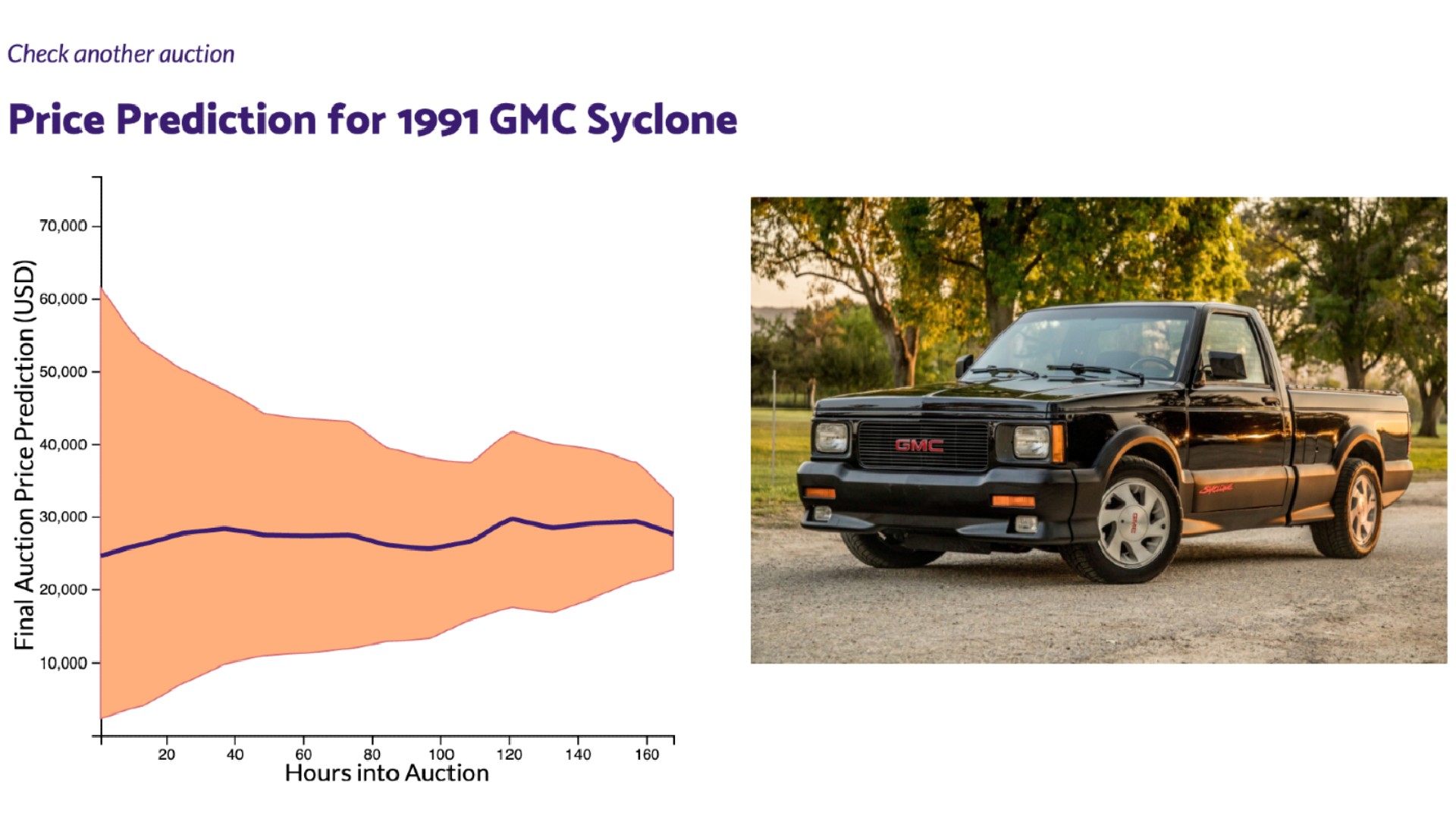

Gaffney said that his models take snapshots every 12 hours from the moment an auction starts to the moment it finishes. Each snapshot uses historical data from past auctions and compares it to the current auction at that point in time. There may be some cases where incomplete data exists, so the model was created to accommodate the uncertainty.

The tool measures the typical amount of error in each model, like how far off each 12-hour “guess” is, and uses that information to build in an upper and lower bound on the final price prediction. Gaffney says that this has made the predictions quite accurate, and notes that it has been exceedingly rare for an auction to finish outside of the set boundaries.

Because all of that isn’t ambitious enough, he has an email service where users can sign up to receive inventory analyses on specific vehicles. This includes a calculation of the rough odds that another vehicle of the same make or model will surface for auction again in the next 90 days and measures the likelihood that at least one of the new auctions will close at a lower price point than the most recent sale.

The chart above shows one of Gaffney’s models and the actual sale price versus the model’s predicted sale price. It was taken from the end of the auction, where the prediction is at its most accurate. The tight grouping in a linear pattern is a good output for the model because it shows that the predictions of each sale were quite close to the actual hammer price. The further outside of that loosely diagonal line a data point falls, the less accurate the final guess.

Of course, there are plenty more specifics involved in creating such a spot-on tool. To get a full grasp of the mechanics behind Gaffney’s project, he has made his notes available online.

As for what’s next, Gaffney says he’s working on building out the models’ predictive abilities, which will help it fill in the gaps of missing or incomplete auction data.

On the topic of his Saab, it’s still up for sale—the old fashioned way—though he mentions he’s currently hunting for his next bad idea.

Got a tip? Send us a note: tips@thedrive.com