You might recall that back in 2015, Domino’s made a big deal out of turning a fleet of Chevy Spark hatchbacks into the ultimate pizza delivery vehicle. The Domino’s DXP, as it was called, might seem like a frivolous project steeped in some not-so-clever marketing, but a recent thread on Twitter by the lead designer on the project proves otherwise. As with all design projects—especially good design projects—there’s a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes that the end-user will never know. More often than not, it’s absolutely mind-numbing (this is coming from someone with a degree in industrial design) but in this case, it’s actually pretty cool. The business of pizza delivery, as it turns out, is one where even thirty seconds can make a huge difference.

Nicolas de Peyer—the former project lead for Local Motors (yes, the people who make the Rally Fighter)—explains how, and why they needed to find that thirty seconds in the long twitter thread, but I’ll summarize it here for you. Twitter isn’t really a great place to delve into intricacies of designing a pizza delivery vehicle.

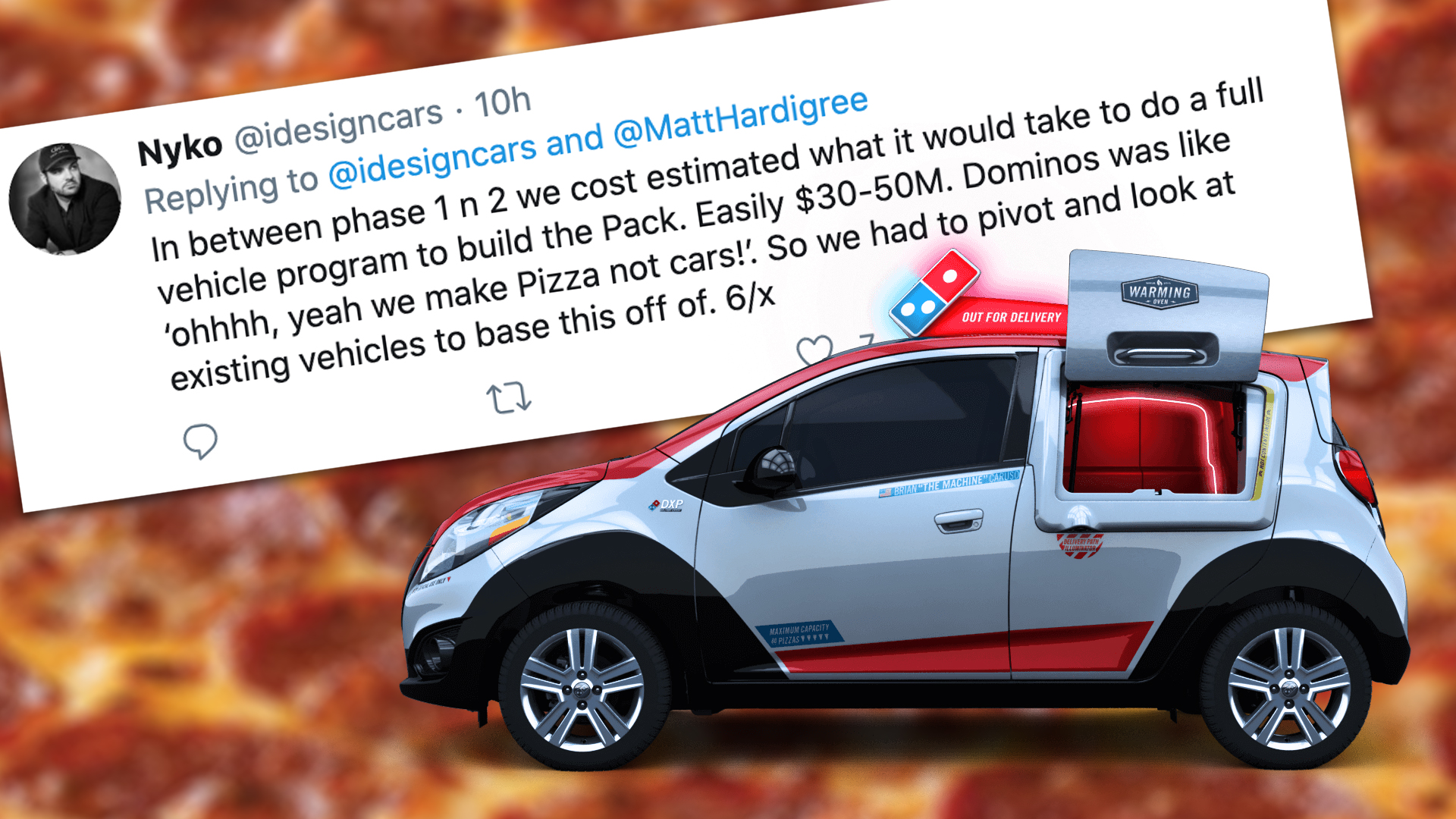

The first thing you need to create a custom pizza delivery vehicle is, of course, a car. But the design team didn’t just land on the Chevy Spark immediately. At first, Domino’s wanted to design a completely bespoke vehicle, and Local Motors dutifully launched a design contest for the public.

Ten finalists were picked out of around 300 serious entries, and the eventual winner—the Domino’s Pack, as seen below—was sketched out by Anej Kostrevc, a talented designer from Slovenia. It looks like a very intense golf cart.

But Domino’s was completely unaware of the costs associated with doing an ambitious ground-up project like building the Pack. Local Motors determined that producing it would cost anywhere from $30 to $50 million, which is a lot of pizza. Domino’s immediately scrapped the Pack and followed Local Motors’ original suggestion of finding the right existing vehicle to convert. To quote de Peyer, “Dominos was like ‘ohhhh, yeah we make pizza not cars!”

A pivot due to a client suddenly understanding their cost constraints is very typical of a design project. Luckily the team wasn’t very far down the road on the Pack when the plans had to change. And that pivot to an existing model was deliberate and informed, not just a decision based on whatever beater they could get for the cheapest. In fact, several cars were considered for modification into the ideal pizza delivery machine.

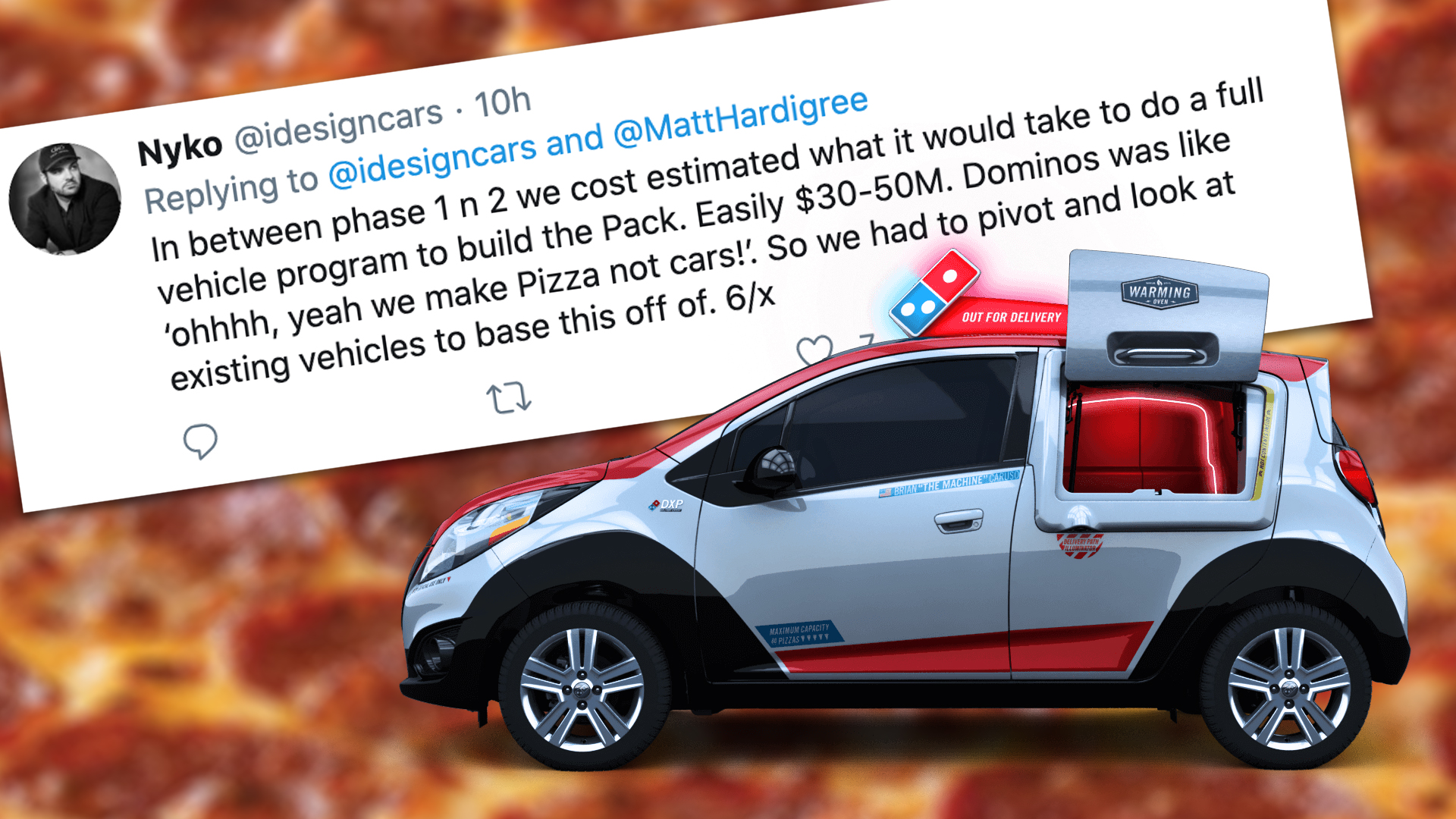

de Peyer says that the Chevy Spark won out “due to [its] great efficiency, good price, good service network, ease of parking, and enough room for most deliveries.” But of course, just choosing the vehicle was the tip of the iceberg. The Pack design from earlier was still in the mix, and the design team had to figure out how to adapt the Chevy Spark into a something resembling Domino’s favorite concept.

But then—and this is typically the most eye-opening part of the design process—actual humans got involved. Domino’s provided a few consultants to advise Local Motors, including one of their delivery drivers who understood the practical needs for the design. And after he was in the picture, everything changed.

Delivering pizzas is an incredibly taxing and demanding job that doesn’t pay well, one made all the more difficult by the fact that, as Ken informed de Peyer, “Normal cars suck for pizza delivery. Seats are designed to hold butts, not pizza. Doors are designed for people. Loading in a heatwave bag with soda, securing it, and keeping it secure took time. Every driver had jerry rigged systems to keep pizza safe and level.”

Setting up those ad-hoc pizza holders unnecessary time. de Peyer realized that the ultimate pizza delivery vehicle is not one that looks like a prop from The Fifth Element, but one that’s completely built around making the life of the driver easier—and making them more money.

Saving just thirty seconds per delivery would allow the average Domino’s driver to complete between 1-4 extra deliveries in a shift. Extrapolate those extra tips over the course of a year, and delivery drivers stood to make at least an extra $3,000 if they had a more suitable tool for their job. This would also encourage drivers to forgo the gas+mileage reimbursements that come with using their own cars, which seem like a good deal upfront but tend to fall short of actually compensating for mechanical wear and tear.

To save that vital thirty seconds the aesthetics of the vehicle were not really relevant, it was about the functionality and the ergonomics.

And ergonomics is often a word that gets thrown around and abused. Somehow it’s ended up meaning keyboards and mice that perfectly conform to the shape of the human hand. Or finger-shaped indentations on the handle of a drill. In reality, the translation of the word ergonomics from Latin is “work study.” Ergonomics is the science of making people work more efficiently. If my design history classes serve me right, it started with specially shaped shovel handles used by factory workers that prevented back injuries. This allowed the factory owners to make more money, of course.

Also informing the DXP’s design were Domino’s Head Chef, the company’s CMO, a Franchise owner, a project manager, and an outside consultant who had lead GM’s EV-1 project. But really, the car’s eventual setup comes down to the input our hero Ken, man of the people. The pain point had been located: shortening the time-consuming process of securing pizzas and two-liter soda bottles for transport.

That focus is how the final design ended up incorporating the iconic pizza oven door in place of the spark’s rear driver side window, which pulled double duty as a marketing stunt and a functional piece of equipment that could warm pizzas to 140 degrees. Inside, every seat but the driver’s was removed and replaced with various easy-access storage solutions. In total the DNX ended up being able to hold 45 pizzas and a dozen large bottles of soda.

The public might’ve smirked, but delivery drivers liked it. It saved the time it said it would, fulfilling the design brief to the tee. The only complaint leveled at the vehicle was that the special pizza door on the side of the car sometimes didn’t seal quite right, but I would say that’s an acceptable flew for a custom vehicle of such a short production run.

Reading this Twitter thread I keep reminding myself that all of this design work was done simply to ensure pizza was delivered properly. The amount of man-hours that go into something as simple as that is truly unbelievable, and we all take it for granted. That’s often for good reason, the design process can be arduous and frustrating—especially when engineers get involved—but it’s great when a background story like this pops up. It helps us all understand the almost entirely invisible workings of an industry that is often unappreciated.

Got a tip? Send us a note: tips@thedrive.com