The next time you dig out The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift to once again revel in its drifting magnificence, send up a little thank you to the universe for Toshi Hayama. Because of his familiarity with the scene and his vast knowledge of drifting, Hayama was hired to oversee the film’s authenticity to the culture.

Back when Tokyo Drift was in pre-production, Hayama was the then-main emcee for the D1 Grand Prix professional drifting series. He had appeared on the Discovery Channel’s drifting documentary and worked as a content creator for the tuner magazine JDM Insider. But he was about to make an even more permanent mark on the scene: Through a network of business and personal connections, Hayama was tapped to be a technical consultant for the third Fast & Furious movie.

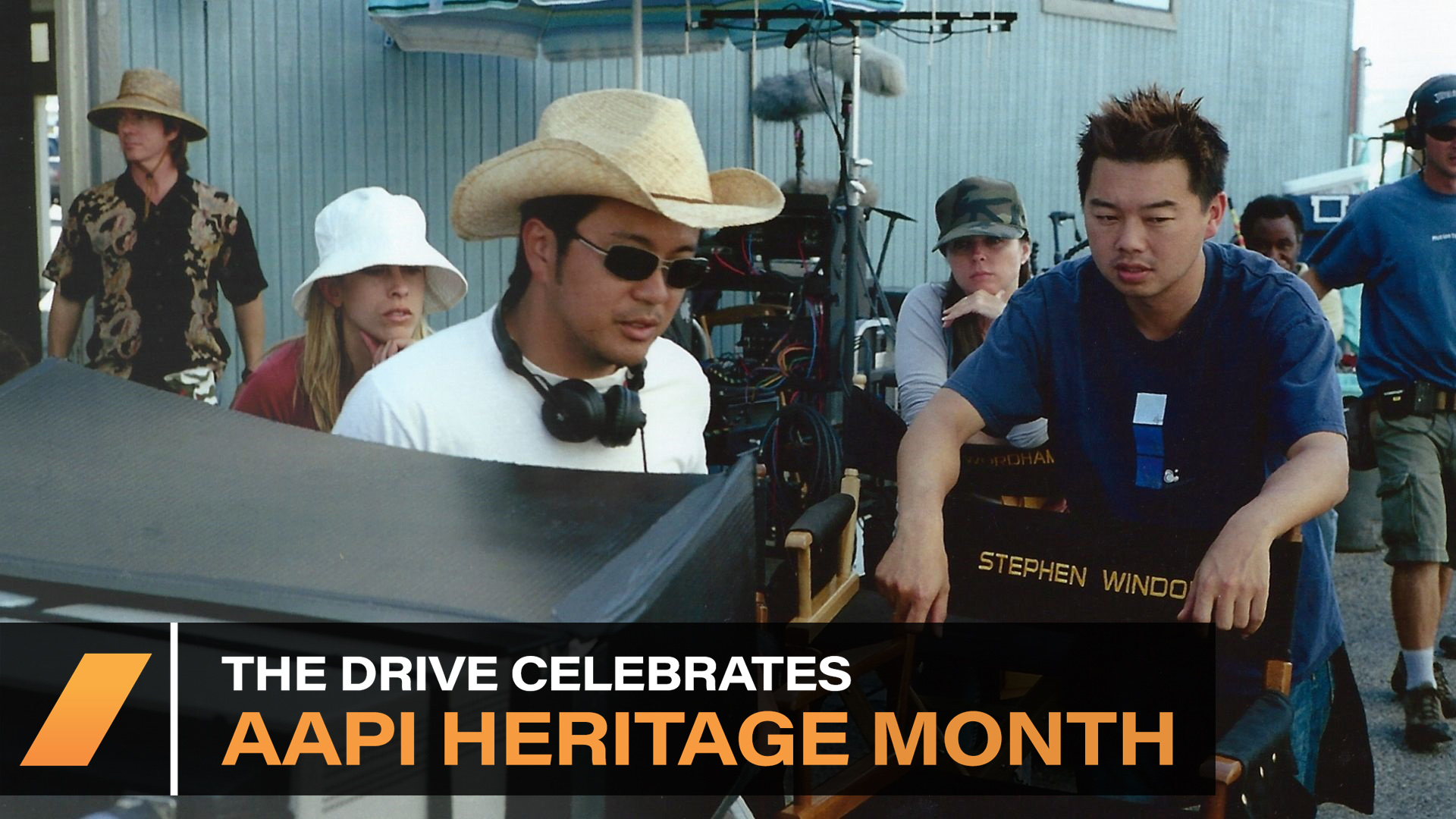

Hayama’s company, Apex Integration already had the top championship drifting team in Japan by the time he started working with Tokyo Drift director Justin Lin. In addition to being the official emcee of D1 Grand Prix, Hayama was also working with Keiichi Tsuchiya—the real life Drift King who appeared in a Tokyo Drift cameo—and was also known for his street racing videos with JDM Insider. Around the same time, Lin was already known for his debut film Better Luck Tomorrow. One of the main actors in that movie was Roger Fan, a former classmate of Hayama’s at boarding school. Fan was already in Lin’s inner circle, so he put in a good word for Hayama.

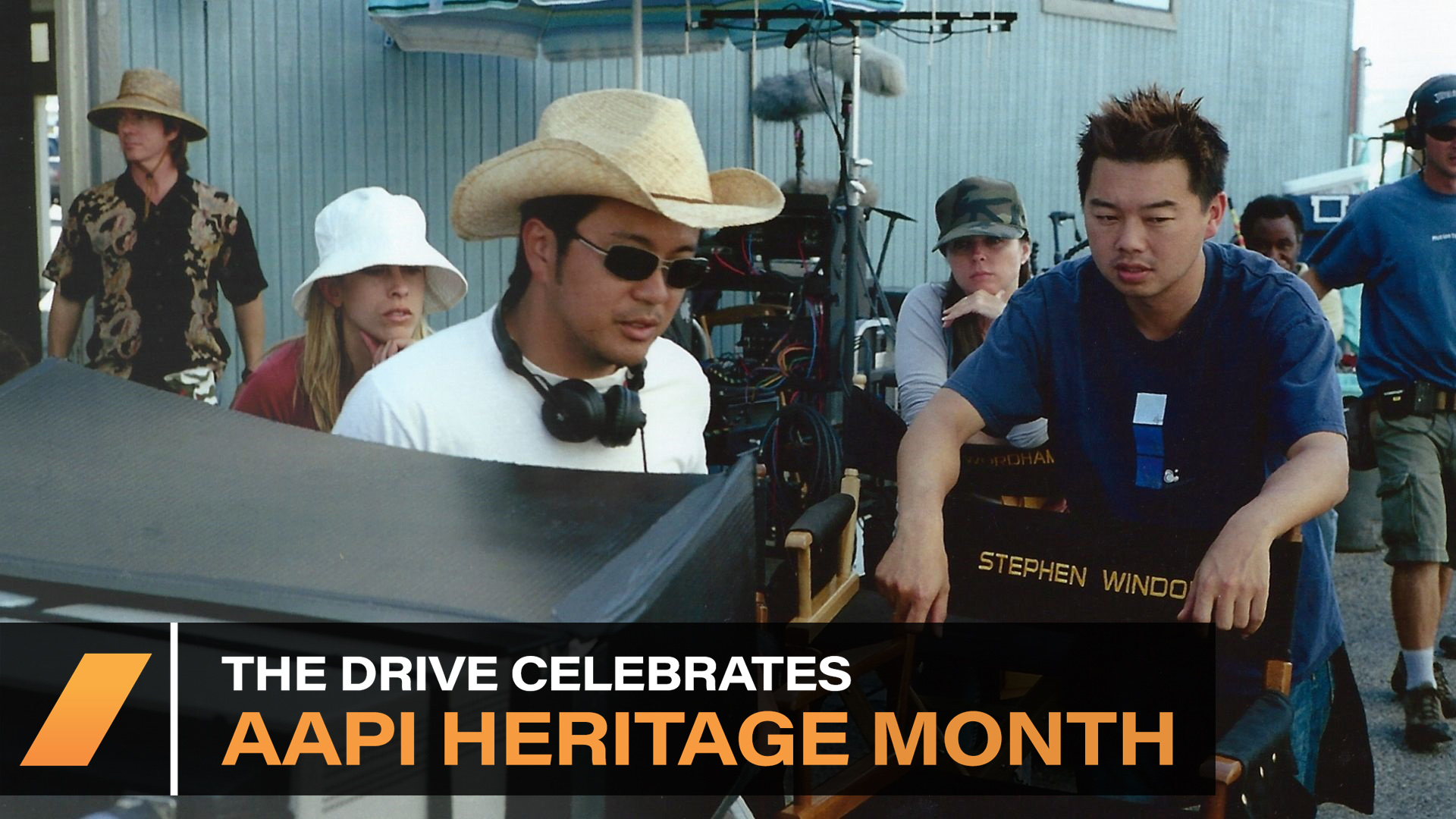

[May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Here at The Drive, we’re celebrating it by lifting up and highlighting AAPI voices in the automotive space. Our hope is that in driving visibility, we can help make the car community an even more welcoming space—to convince those who perhaps have not always felt like they belonged that they absolutely do belong here. Diversity in perspectives and backgrounds only strengthens the group as a whole. It is why representation matters.]

“That referral was a badge of trust, which in Hollywood is extremely important,” Hayama tells me in a recent interview. “It was also important because we were in uncharted territory with a franchise that was originally supposed to go straight to video. No one knew how this would turn out, so we were always fighting the accepted norms to create something that would last.”

Once he was on set, Hayama was tasked with correcting any inaccuracies in the script and worked hand-in-hand with director Justin Lin to ensure the movie was true to the real world of drifting. Harnessing Hayama’s expertise, Lin was able to create authentic action sequences, including the parking lot and canyon scenes. You might not be able to pick them out of a lineup, but Hayama’s legs and feet were featured as body doubles for many of the pedal and shifting sequences.

Tokyo Drift was Lin’s first blockbuster movie, and he brought in trusted friends and crew to ensure he could focus on the storytelling. Having that endorsement from Fan cemented Hayama’s position in the inner production circle, giving him access to much more than being a traditional technical consultant could and the freedom to move around.

“From day one, my job was to bring authenticity and credibility to the movie,” Hayama says. “The script I first received was full of errors, the hero cars had ridiculous setups, and the racing sequences were not all complete. I asked to tone down the design of the cars, as well as give input on realistic yet unique and original vehicle setups. The point of Tokyo Drift was not to make a documentary, so it had to be larger than real life. With that being said, I pushed very hard every day to ensure that real drifters and real cars with real engines were used, with the least amount of CG effects. Justin [Lin] was really open to this, and he was the one who nudged me into doing a cameo in the parking lot garage and airplane scenes.”

The movie also used pro drifters like Rhys Millen, Samuel Hübinette, and Tanner Foust as stunt drivers—friends of Hayama’s who had been working in Hollywood already. Together, they added a huge level of credibility. Hayama was the backup and confidante for the director, giving Lin the support he’d need to make big decisions without looking like a fool or sellout in front of the emerging drifting community.

“There were many instances in which the movie could’ve very well gone the wrong way, but to his credit, Justin pushed and negotiated very hard on our behalf for certain things that he could not compromise on,” Hayama says. “Some of these included the cars, stunts, and shooting locations; cost was always a factor and he really pushed for as much authentic Japan as possible. He paid respect in the community where it was due, and I think that contributed a lot to the movie’s cult-like success. Tokyo Drift did not win any Academy Awards, but the reason why it grows on you is because in the end, it’s great driving with real drivers and real life references.”

The movie also withstands the test of time because, at its core, it’s a story about fitting in and finding your community. Like many before—and, indeed, after—him, Hayama was able to find kinship through his love for cars. Not fitting in easily with the town he grew up in is where that love first took root.

Hayama’s parents met at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, moved to Japan, and then back to Newport Beach, California, after he was born. He says he was a foreign kid in a surfer town; he was one of just a few Asians at his school right after the end of the Vietnam War. Teenage years are hard enough, and Hayama had the added challenge of being what he calls, “the weak, skinny kid.” He didn’t have an affinity for the sports many of the kids in his school were into, but luckily, he found kinship in the band and skateboard communities. In the meantime, his true passion was fueled by gasoline.

By the time he was 15, he was tired of taking the bus 20 minutes down the Pacific Coast Highway to school and begged his parents for his permit. On the day of his 16th birthday, Hayama’s parents let him take over his dad’s Toyota MR2.

“I took off and I was free,” he tells me. From there, Hayama experimented with street racing in the early ’90s, joining an Asian-American fraternity at the University of California, Irvine that had a strong connection to the local scene that inspired the first Fast & Furious movie.

“We’d meet at Denny’s in Gardena, near Compton, and you’d see 100 to 200 cars coming in at once,” Hayama says.

Hollywood and the intense world of drifting and drifting stunts may have been a standout moment, but outside of that, Hayama’s been able to turn his passion for cars into what will hopefully be a lifelong career in the automotive world.

After graduating from college, Hayama started a parts aftermarket company in his living room, selling exhaust systems and fuel management systems. Originally, he thought it would be a great way to get parts for his own car. At that time, he owned the equivalent of an Eagle Talon/Mitsubishi Eclipse and one of the first federalized Skyline R34s. But the company kept growing, so he was able to build a racing team while his company achieved millions of dollars in sales.

During that process, Hayama hosted Japanese engineers from his company and learned how to translate for meetings, which surprised him because, “My Japanese was terrible when I was going to Japanese school as a kid,” Hayama laughs.

A call from a friend changed his direction several years ago. Lexus was launching the RC and needed a translator for media events. Hayama figured it would be a one-time gig and then he’d move on. But as it turned out, he had a knack for translating, and Lexus executives kept inviting him back.

“Running the Japanese tuning parts business for ten years and working in motorsports with the mechanics really honed my technical jargon down to the frequencies, ohms, and engine materials,” Hayama says. “To work with Lexus and Toyota, I had to combine the technical jargon with regulatory terms, brand-specific terms, and OEM-specific terms. Catching up on that side was a little bit harder than I expected; coming from the enthusiast side, I figured car stuff is car stuff, but it’s so much more than that.”

Motor shows were the most difficult, he says, because he didn’t have enough time to create a comfortable, personal relationship with the chief engineer. Hayama would only have about 20 minutes max to warm up and always had “two or three worried PR people” watching his every move.

“It was very difficult to make sure that I could hit all the points that they wanted with almost no preparation,” Hayama says. “I was saying what they said, but my words would be the ones that triggered a response from the journalist, so word choice was particularly important, especially for sensitive topics where something could get misconstrued. Nuance is really important to me. In my brain, translation is like using a router; I listen and pick up three keywords for every sentence, and then I reiterate what is said in Americanized English. I might miss a few words, but I make sure I never miss the point and the way the speaker is saying it without diluting the core message.”

It was in this setting at the Lexus LS launch several years ago, hosted at the Skywalker Ranch in California, that I met him. During the presentations, it was Hayama’s job to take questions from the media, translate them for Lexus executives from Japan, and then relay the answers back to the crowd. It’s a job that requires concentration and poise. And a great deal of trust.

“Being an aftermarket guy and now working in the OEM side, getting to drive and review camouflaged vehicle prototypes is a dream come true,” Hayama says. “I feel like it’s my job to be that specialty tool to allow the true message of the engineers, design team, and everyone who works so hard to build these cars, to get out into the world. It’d be nice if my example could inspire other young kids with dreams to make a career out of something they love.”

Right now, Hayama is back in Tokyo with his family, and they are planning to come back to California in the near future. He’ll probably be on the road with Toyota and Lexus again, helping American media and audiences better understand the minds behind the designs. Meanwhile, look for Hayama’s cameo appearances during your next Tokyo Drift binge. It’s because of him that the movie’s drifting scenes are credible and believable.

Got a tip? Send the writer a note: kristin.shaw@thedrive.com