Q: I binge watched 900 hours of the Barrett-Jackson Auction on Velocity this past weekend. Considering the insanity of the prices, should I be investing in collector cars? – Ricardo Cabeza, Downey, CA

A: First, congratulations on surviving the inane, all-cars-well-bought, all-prices-reasonable, all-obvious-commentary coverage of Barrett-Jackson. I, too, cannot resist watching guys wearing Hawaiian shirts and oversized Panerais bidding on muscle cars while drinking mimosas. It’s mesmerizing in the same way as watching a Labradoodle sniff his own rectum.

But collecting isn’t merely a horrible, destructive and retirement-threatening investment: It’s the worst thing you can do with a car. Permit me to screed on.

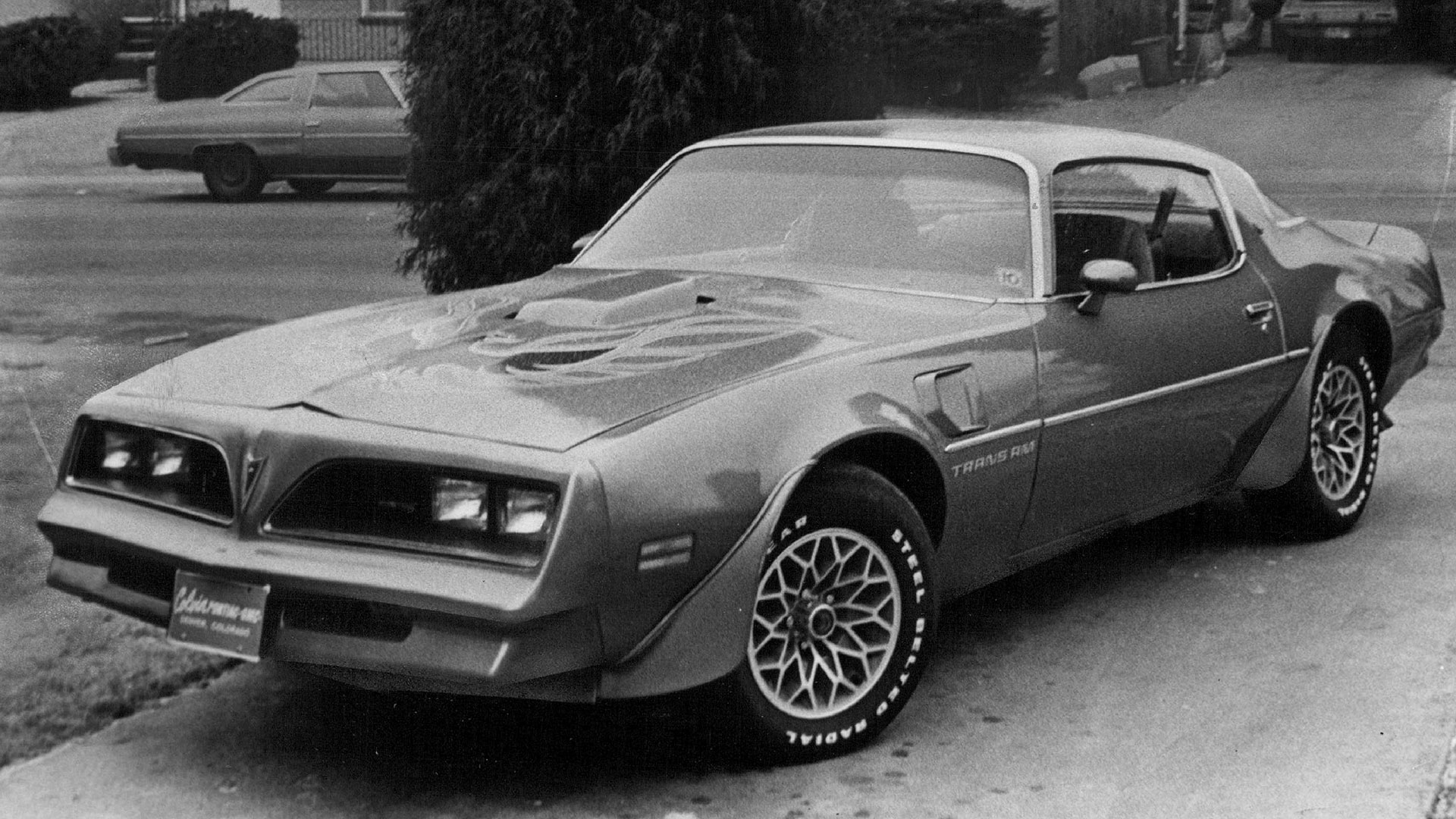

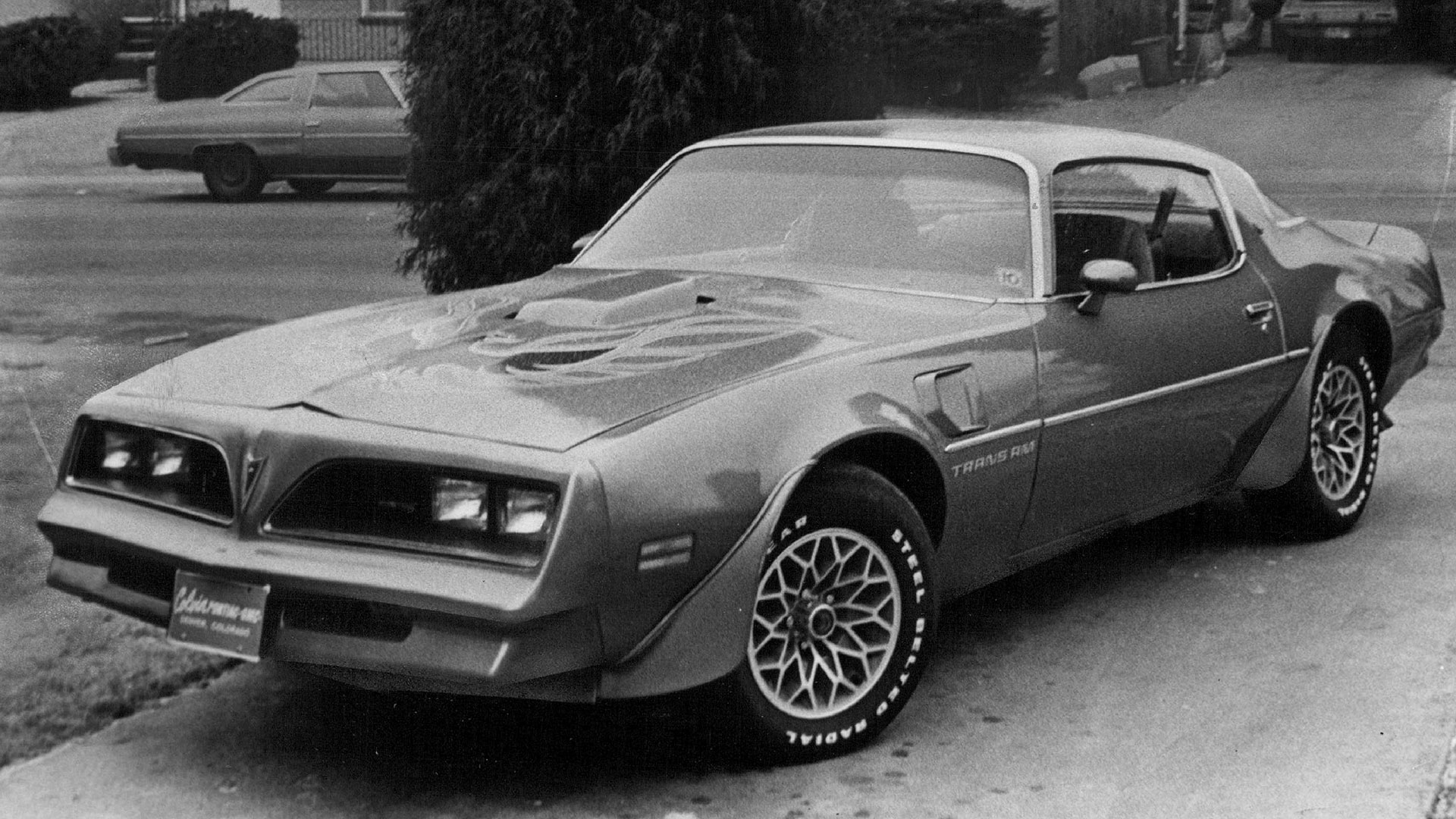

There were plenty of insane purchases at Barrett-Jackson last weekend. For instance, NASCAR team owner and car mega-dealer Rick Hendrick paid $110,000 for a 1979 Peterbilt that had portrayed Optimus Prime in the first Transformers movie. And some car museum in Florida paid $550,000 for a 1977 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am that Burt Reynolds owned—but which had not been used in filming Smokey and the Bandit. But there was one auction that particularly pointed up the absurdity of collecting cars.

Lot No. 763.1, a 1979 Trans Am 10th Anniversary Edition showing a mere 7.9-miles on its odometer. That’s an average of a little over 2/10ths of a mile for each of its nearly 37 years. That sold for $170,000, which, after paying Barrett-Jackson its 10-percent vigorish, totaled up to $187,000. That’s almost $200k for a car with cart springs and a massive 6.6-liter lump of Pontiac V8 that can only muster 220 horsepower. A lousy car by any reasonable modern standard.

According to Barrett-Jackson, the car was bought new on March 29, 1979 by a farmer who paid $15,000—a $4,177 markup over the original $10,822 sticker, and the equivalent of $48,970 in today’s dollars. And then he parked it and never drove it. For a 6.79 percent annual return on investment.

By 2016 standards, when many interest rates are virtually zero, 6.79-percent sounds pretty awesome. But, in 1979, the ten-year United States Treasury bonds were paying 9.10-percent with virtually no risk. Plus T-Bills don’t need a garage to be parked in, never leak any oil, don’t require insurance, and the farmer wouldn’t have had to worry about mice getting inside them and eating all the wiring. Continually reinvesting in further bond issues—boring, safe, Treasury bonds—would’ve essentially duplicated the Trans Am’s appreciation to $170,000 in 2016.

Of course if the farmer had waited until 1980 and put his $15,000 into Apple (AAPL) stock when it went public at $22 a share, then held onto it, he’d have (after four stock splits) about 38,182 shares of the most valuable company on Earth with an off-peak value of $3.71 million.

But what’s awful about these preserved-in-amber unicorns, like the farmer’s Trans Am, is that they’re never driven. They’ve never been to a prom or a drive-in or even an office building. No one has ever taken them on a long trip to get over some trauma, or wound them out for a little impromptu stoplight-to-stoplight fun. All they’ve ever done is sit in a room accumulating dust instead of history.

Ultimately, any car’s value is purely extrinsic; it’s what we see and do and experience that makes it worth more. That farmer’s Trans Am is a mummified representation of it’s most uninteresting moment: Sitting in a showroom. That it has been disinterred and found a sucker who finds $187,000 worth of value on that is kind of, well, sad. Because the only thing that can happen to this car now is that it will be moved into its new owner’s collection, embalmed and put on display again. It’s not a car any more; it’s the equivalent of Lenin’s corpse.

Oh, and it’s bound to go down in value, too. Not just because the collector car market goes bust pretty regularly, but because the Trans Am 10th AE will mean virtually nothing to the generations that were born in the Eighties, Nineties and beyond. Show most high school freshman a photo of the car now, and they’ll shrug their shoulders. When they reach buying maturity, they won’t be climbing over each other to relive someone else’s childhood in 2053.

Cars should be consumed. Driven, used up, and recycled or restored. Old racecars should still be racing—thankfully, many are. And old Trans Ams should at least still be a date night car for people trying maximize their Medicare benefits. Old cars should still be making personal history for their owners.

Ah, whatever. In a hundred years, if this old Pontiac survives, the undead zombies that rule the future won’t know what they’re looking at… and won’t care.