Good morning and welcome back to Speed Lines, The Drive’s a.m. roundup of what matters in the world of transportation. It’s May 18, and that means today marks the cautious, tepid reopening of many of America’s automotive factories. Let’s dive right into all of that.

The Restart Begins

After being idled since March, more than 50 Big Three automotive plants—in Detroit, Chicago, New York, Missouri, Ohio and more—are opening their doors today and allowing workers back in. It won’t be full steam ahead for many reasons we’re about to discuss, but this is the restart day for Ford, General Motors and Fiat Chrysler in North America. (Here’s a pretty comprehensive list of who’s back.) In previous weeks, Toyota, Honda, BMW, Mercedes-Benz and more have restarted their U.S. plants as well; now it’s time for the American automakers to do the same.

This is a big deal for obvious reasons. The global auto industry has been battered by the pandemic and its subsequent stay-at-home orders and economic downturn, and while some buyers have taken advantage of big deals on trucks and SUVs, sales and profits for all automakers have been abysmal. Dealer supplies are beginning to run low for trucks, especially. And factory workers, salespeople and everyone else whose livelihood depends on this industry have bills to pay.

But this restart is also a major test of whether large-scale American manufacturing can be done safely, without reinfections, worker deaths and supply chain disruptions. As a result, this will be “a slow and arduous process,” as the Wall Street Journal put it today.

GM says it will take at least four weeks to return to full production, and its output will be dependent on buyer demand. Ford’s operations chief Jim Farley said Thursday he isn’t sure when the company’s U.S. factories will resume full output.

Automakers in all are expected to produce fewer than nine million vehicles in the U.S. this year, the lowest output since 2011, according to industry research firm LMC Automotive.

Some car companies are taking pains to reassure staff that protection is paramount. GM last week sent care packages to all of its nearly 100,000 factory and office U.S. employees, complete with face masks, return-to-work information and a letter from Chief Executive Mary Barra.

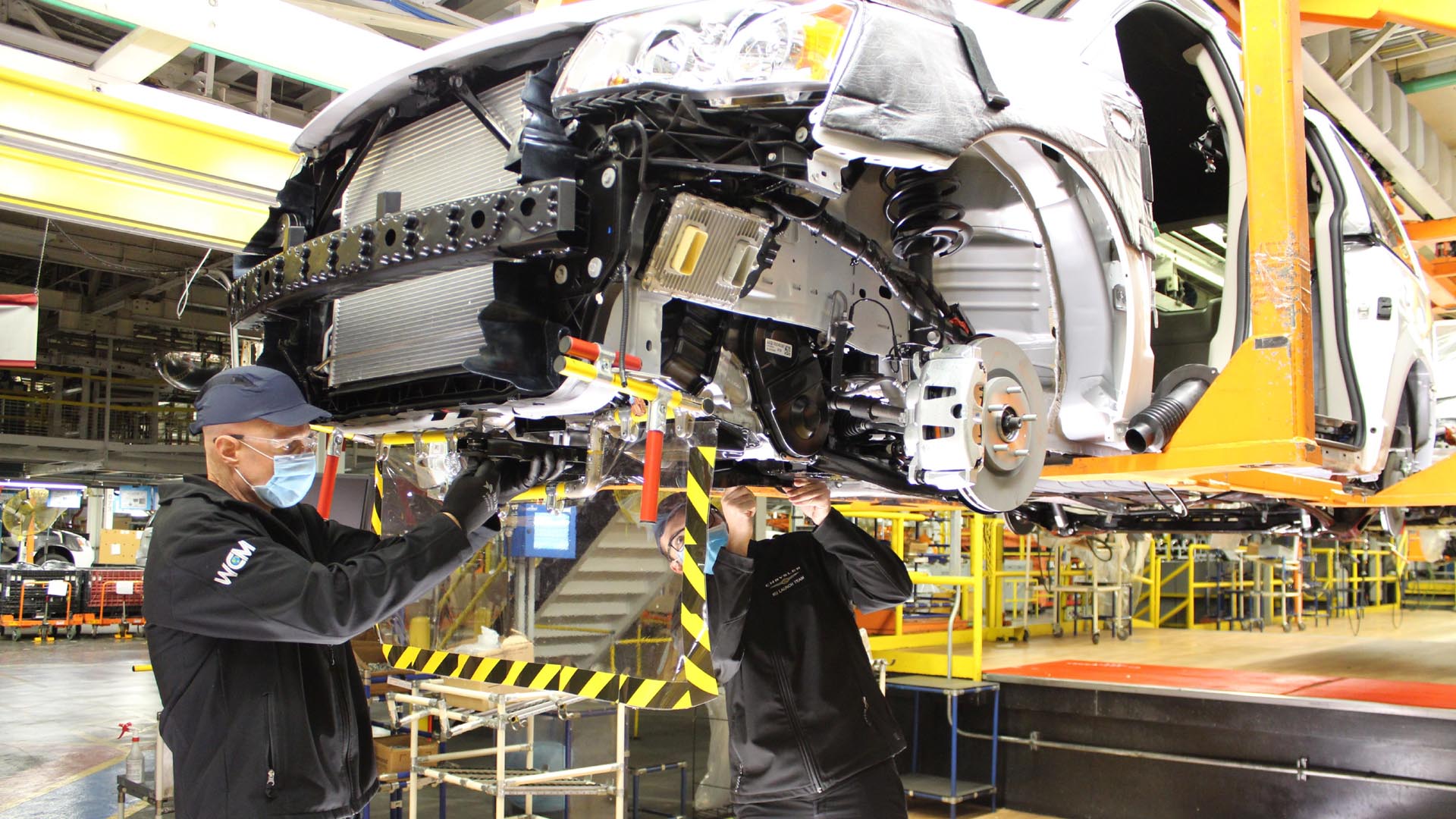

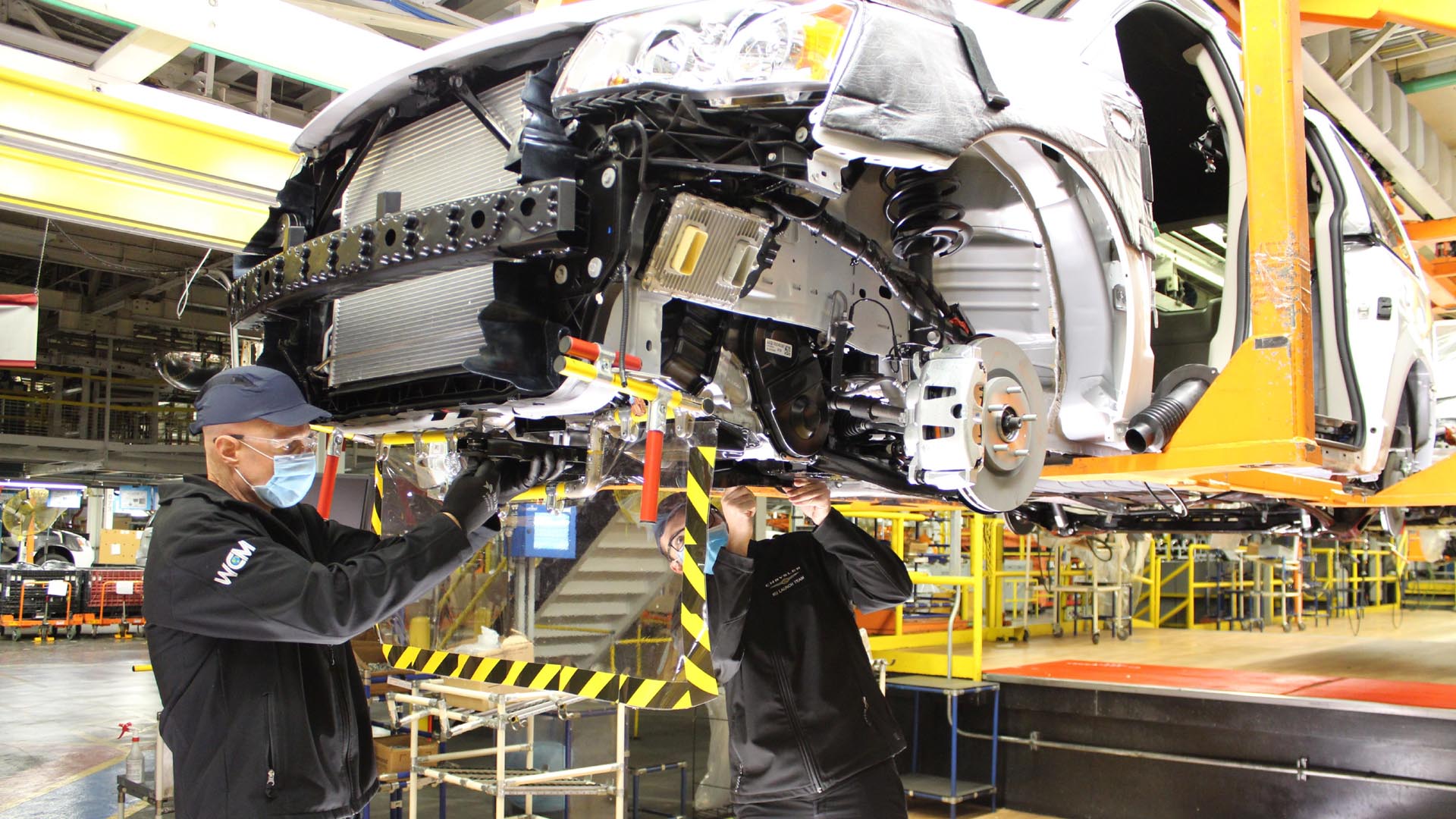

Those workers will return to a markedly different atmosphere than the one they left. FCA, for example, has a rundown of everything it’s doing: daily cleanings, daily temperature checks, mandatory masks and goggles, plastic partitions on the assembly lines and in break rooms to separate workers, some 17,000 workstations modified for distancing, thermal imaging cameras to detect fevers and equipment packages mailed to 47,000 employees. GM and Ford are, of course, taking similar measures.

It’s all very aggressive, and a lot of it is gleaned from precautions taken at Asian factories when that region was the epicenter for the virus earlier this year. Still, it’s a scary proposition for workers.

How Do Workers Feel?

One UAW Local president says “Some people are looking forward to coming back and some people are concerned. It’s a balance between the two,” according to the Detroit Free Press. But I can’t imagine there are many people who are doing this without at least some trepidation. As another story from the paper notes, the Detroit area, to use just one example, has been hit especially hard by the pandemic. It’s one of the worst U.S. regions for it after New York. And the industry itself has seen numerous workers die of COVID-19 in recent months.

So while factory workers have bills to pay the same as anyone, many are understandably nervous:

The rest said it was too soon or talked about the loss of life from COVID-19. At this plant alone, where the popular, older version of the Ram 1500 pickup is built, the toll has been tragic, with four dead, although it’s not known where any of them contracted the virus.

Jay Peebles of Roseville, who installs seats, worried about his 4-month-old daughter, Jasmine.

“I just think I should be home with my family, my wife, with my child. I don’t think building a truck is going to save lives right now, you know what I mean? But we’ve got to make money so …” Peebles said.

“(My wife) don’t like that I’m back here already this soon, when we’ve lost people at this exact plant. Multiple people. I knew a few of them,” he said, noting that he’s lost people in his family, too, grandparents.

Auto industry officials point to the success they’ve had instituting these measures in China and South Korea. But cleanings and screenings had better run like a military operation for this to work.

The Supplier Problem

Finally, I’ll reiterate that this “restart” won’t be an overnight move back to 100 percent production capacity. Besides the slowness needed to ensure worker safety, and shaky consumer demand for new cars as unemployment skyrockets, there’s also the fact that the entire supply chain has been disrupted for months. Many supplier companies lack materials and orders to call back their workers, so plants will be left without parts needed to make cars. And there’s the fact that Mexico, whose factories make some 40 percent of car parts imported to the U.S., hasn’t reopened yet.

As that WSJ story I linked to above notes, at least one plant—a Daimler plant in Alabama—will have to halt production this week again over issues with international supplier companies. The interconnected, globalized model of building modern cars is great for cutting costs, but in this case, its complexity is more a liability than anything else.

On Our Radar

The missing links to grading Harley-Davidson’s EV pivot (TechCrunch)

Self-Driving Ubers of the Future Will Deliver Stuff, Not People (OneZero)

Mexico prepares to resume economic activity as coronavirus cases continue to rise (Reuters)

Read These To Seem Smart And Interesting

New Yorkers Are Thinking About Getting Cars Because of COVID-19 (Vice)

All the Tiny Moments That Add Up to Make ‘Top Gun’ Perfect (The Ringer)

Doordash and Pizza Arbitrage (Margins)

Your Turn

Is it too soon for factory workers to get back to making cars? What should these plants—and the companies that own them—be doing that they aren’t doing?