In a darkened cave somewhere north of San Francisco, Audi engineers quietly showed off technology currently outlawed in the United States. The forbidden fruit? Headlights. High-tech marvels of optical engineering that can project precision light patterns onto the road ahead, illuminating the terrain cleanly and uniformly while deftly avoiding shining bright beams into the eyes of oncoming drivers. During a demonstration using a handheld light in front of the car—conducted at a winery (hence, the cave) during the launch of the newly redesigned Audi A7—the Audi’s beam dipped and pivoted while masking the individual who was acting as a simulated vehicle.

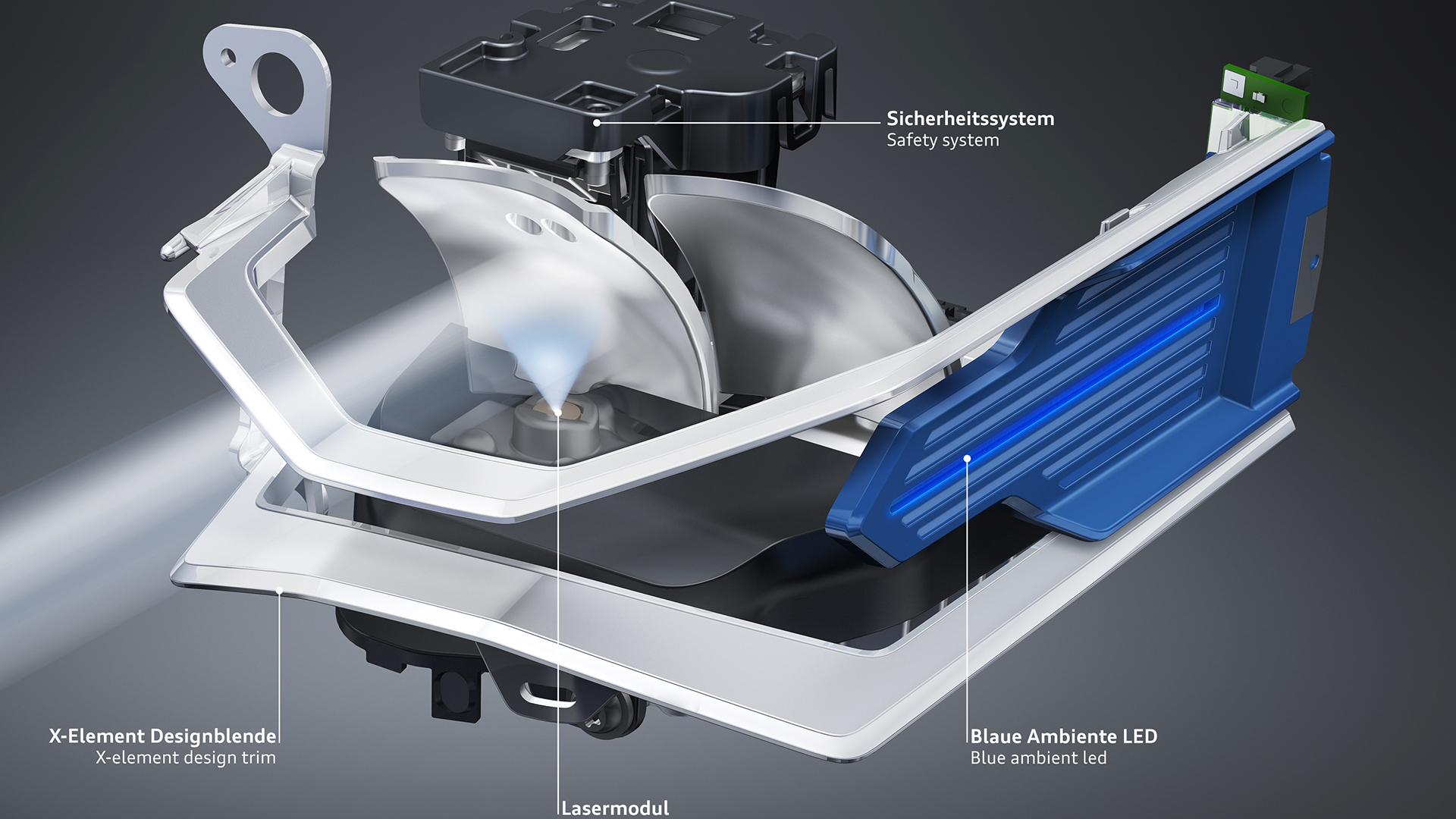

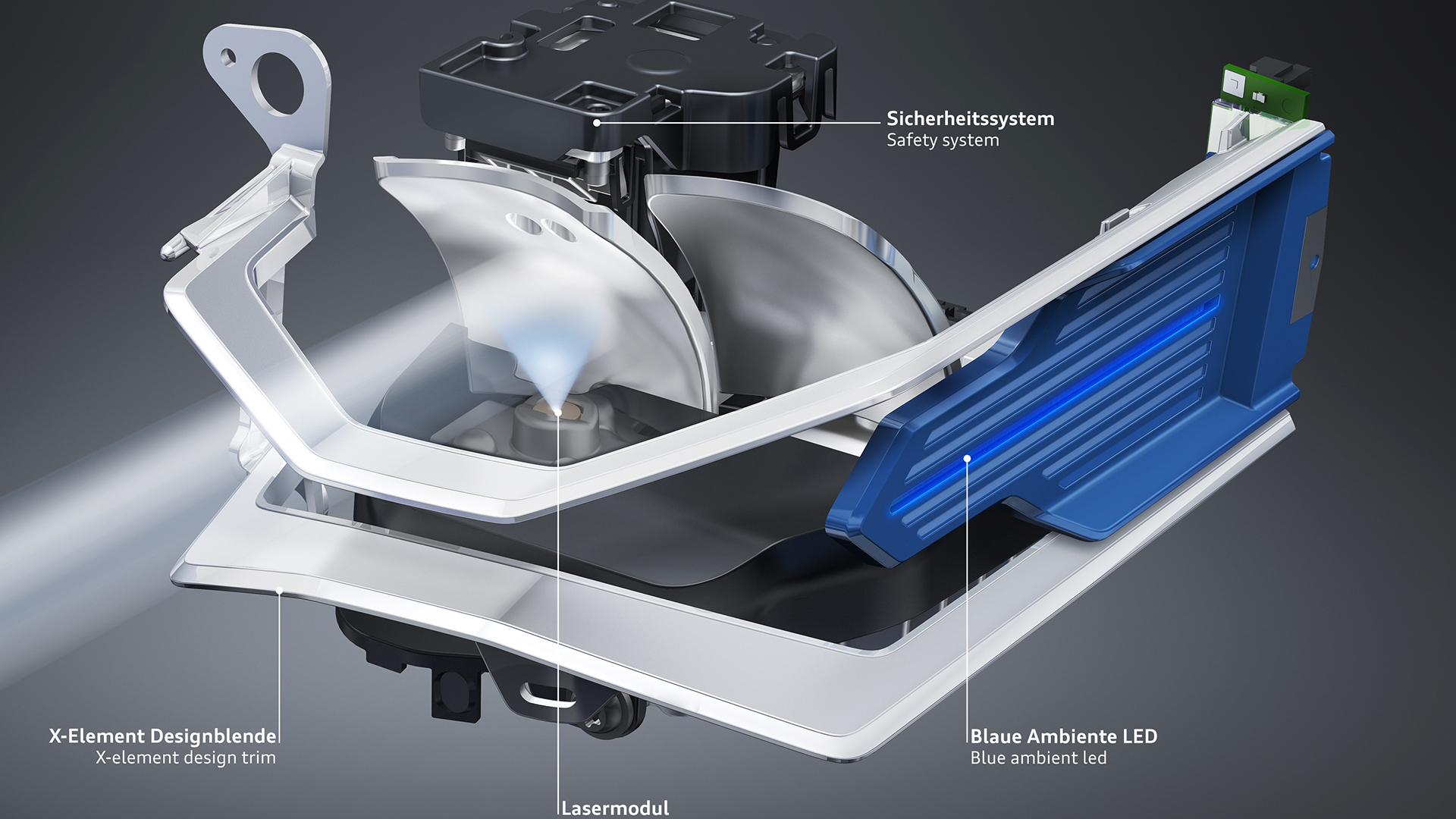

The technology—dubbed “HD Matrix-design Headlights with Audi Laser Light“—uses an LED matrix to executes the dance described above, with a laser spotlight coming on to double the range as needed. The Matrix HD system can be purchased for certain U.S. vehicles—namely the new A6, A7, A8, and Q8—but not used to its full dynamic capability, for the simple reason that regulators haven’t approved it. (There’s still a benefit to buying them, namely, the quality of the light and its ability to adjust its aim with your steering.) The law presently requires separate light sources for the low and high beam, but Audi’s idealized system would be able to integrate them into a single light source, enabling the dynamic shift between low and high beams on the fly. If and when the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration does approve the tech, owners who’ve purchased the light can have the feature activated with a simple software patch. If that doesn’t happen…well, those owners will never know the thrill of the lights they paid for.

The fact that a carmaker allows features to exist, untapped, in its vehicles is nothing new. In fact, it’s almost becoming fashionable. Tesla, for instance, has been installing hardware systems that enable a variety of features long before the systems are either ready for prime time or even legal, activating them via over-the-air software updates when the time is right. These include everything from a dashcam feature (using the car’s existing forward-facing camera) to track driving modes

to increasingly advanced Autopilot capabilities.

Other capabilities are more mundane, but reflect regional variations in thinking. Brake lights, for instance, can be set in Europe to pulse rapidly during emergency braking, but that feature is disabled in the U.S., where it’s illegal.

According to auto industry analyst Jeremy Carlson with IHS Markit, much of this has to do with the simple fact that cars are manufactured for a variety of global markets. “The homologation and approvals process introduces complexities into the automotive manufacturing, especially when you’re designing a vehicle at a global scale,” Carlson said. As a result, cars tend to be hard-wired for things they may or may not be able to do based on their geographic location.

“Every single market has its own regulator requirements, and it’s becoming much more apparent that the technology is moving quite quickly while regulators in certain areas are not,” Carlson said.

But there are other reasons cars are being infused with capabilities that aren’t usable. Carlson notes that Tesla’s strategy hasn’t been just to install the hardware and wait for features to be legal, but for the company to take the time necessary to fully bake the features before activating them. The company installs the hardware and then hones the software, even using data drawn from vehicles on the road to help bolster the R&D process, thus allowing both new cars and existing ones to adopt the features when they’re ready.

Having the hardware present and ready also helps move the ball forward for both individual manufacturers and the industry as a whole—and by extension, of course, the consumer. “It’s helpful that we have an industry that’s leading regulation, in a way,” Carlson said. “It’s one thing to say that this is what we’d like to do—having fully autonomous driving by 2025, say—and we need regulators to help us, and another to say this is what’s presently available in production vehicles and here’s what could be available. It’s a different question, and it’s more tangible for regulators when they can see and experience possible new features.”

But even though it’s de rigeur to preload capabilities into cars right now with the hope or expectation they’ll be deployable within a reasonable amount of time, these systems are still expensive, and it’s not always a foregone conclusion that they will become usable. “There’s always a risk there that you’re asking someone to pay for an option without certainty that you’ll be able to turn it on in the future,” Carlson said.

Though there have been signs of hope from NHTSA regarding permitting alternative headlight strategies that will allow Audi’s Matrix system to fully shine, nothing has been inked yet, nor has any timeline been declared. In-depth semi-autonomous capability is an equally iffy proposition, even though basic capabilities are fully legal. Audi’s new A8—its flagship sedan—comes loaded to the gills with sensors and processors, including the first laser-powered lidar system in a production vehicle and a powerful Nvidia processor, that could enable advanced semi-autonomous capability—but it may not be able to fully tap that hardware before the next generation of the vehicle comes around. Sure, the price for this gear is invisibly baked into the price of the car, but buyers are still paying for it at the end of the day.

But the bottom line, too, is that this hardware has to be integrated into the vehicle and driving experience at some point, and the process for reaching full capability rolls out gradually. In another example, carmakers have begun to switch from 24 GHz radar systems to 77 GHz units; this enables higher-resolution scanning for objects in the vehicles’ vicinity, allowing for classification and tracking with higher confidence. Onboard systems aren’t really able to use that power yet, but upgrading the hardware allows carmakers to add features in the future without having to introduce new hardware. Similarly, systems like Audi’s onboard supercomputer and the 48-volt electrical systems that are starting to appear in high-end luxury cars—which help power a slew of advanced features, even if they’re not always tapped—effectively future-proof the cars against the often years-long development process for any given model.

As for whether we’re overpaying for our technology because of this, Carlson doesn’t think so. “In general—and using the A8’s computer as an example—it does tend to feel like the systems are matched well enough to the capabilities of the vehicle,” Carlson said. “Automakers aren’t going to invest in significant extra technology that nobody will benefit from.”

Indeed, the systems may be expensive, but they’re still being used. They could just be used for a lot more as the years—and the rules—roll along.