Automotive treasures aren’t just $100 million lost Bugattis, though those are nice. Sometimes even a piece of paper can be similarly exciting. Recently, the great-grandson of one Dr. N.B. Tooker, a physician in the U.S.’s War Department, came across a trove of receipts from the 1910s detailing his ancestor’s new car purchases and maintenance over a century ago and shared them with The Drive.

“I came across them in my family’s house, which was owned by my great grandfather,” says Tyler, Tooker’s great-grandson. “They laid in a dovetailed wooden box, practically untouched since he put them there in the early ’20s.” The large box of receipts allow us to trace Dr. Tooker’s growth as a proto-enthusiast, following his first new car, fanatical maintenance, a later trade-in to a more experimental model, and finally some in-period modifications that’ll sound familiar to a 21st century car nut.

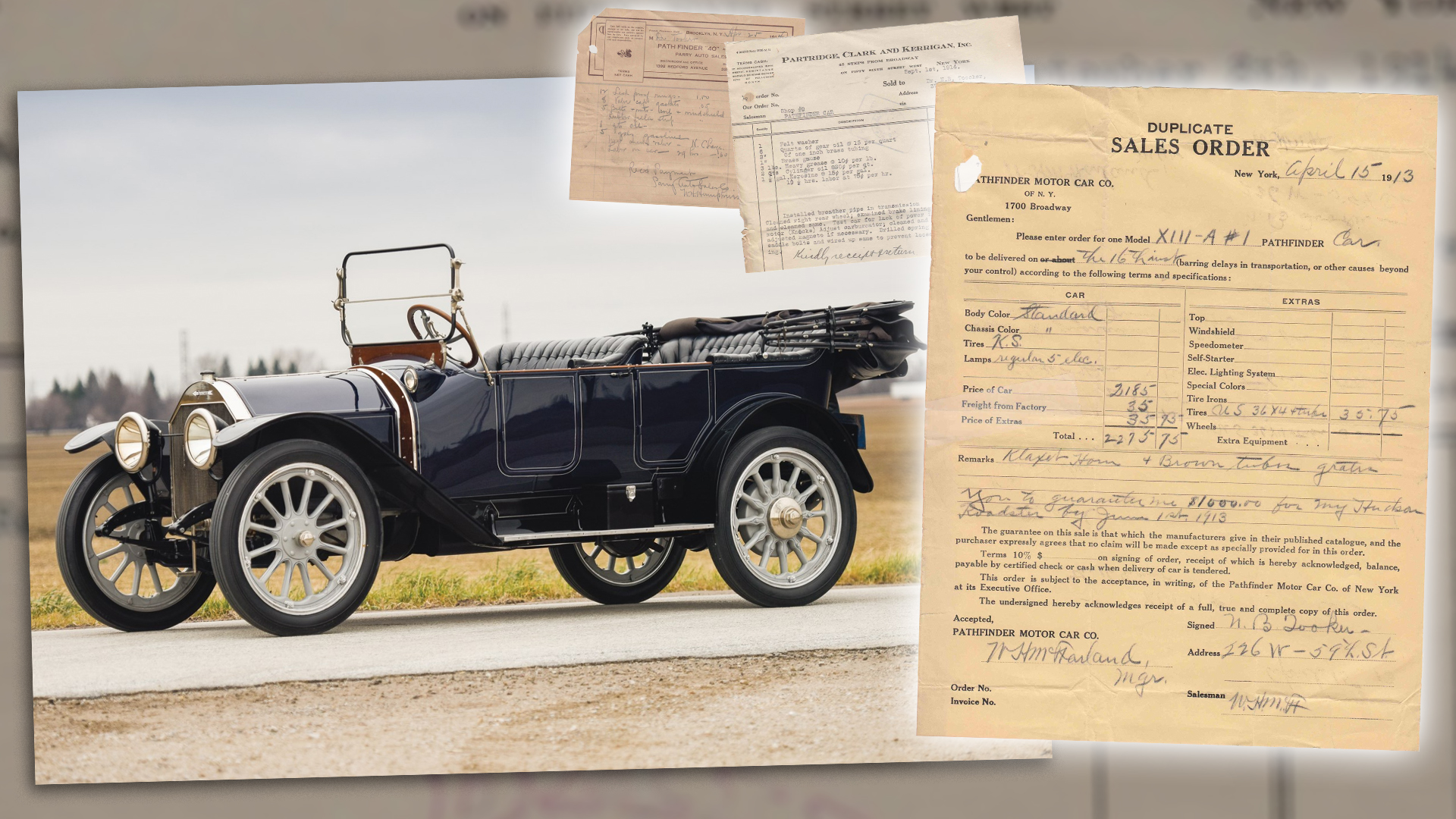

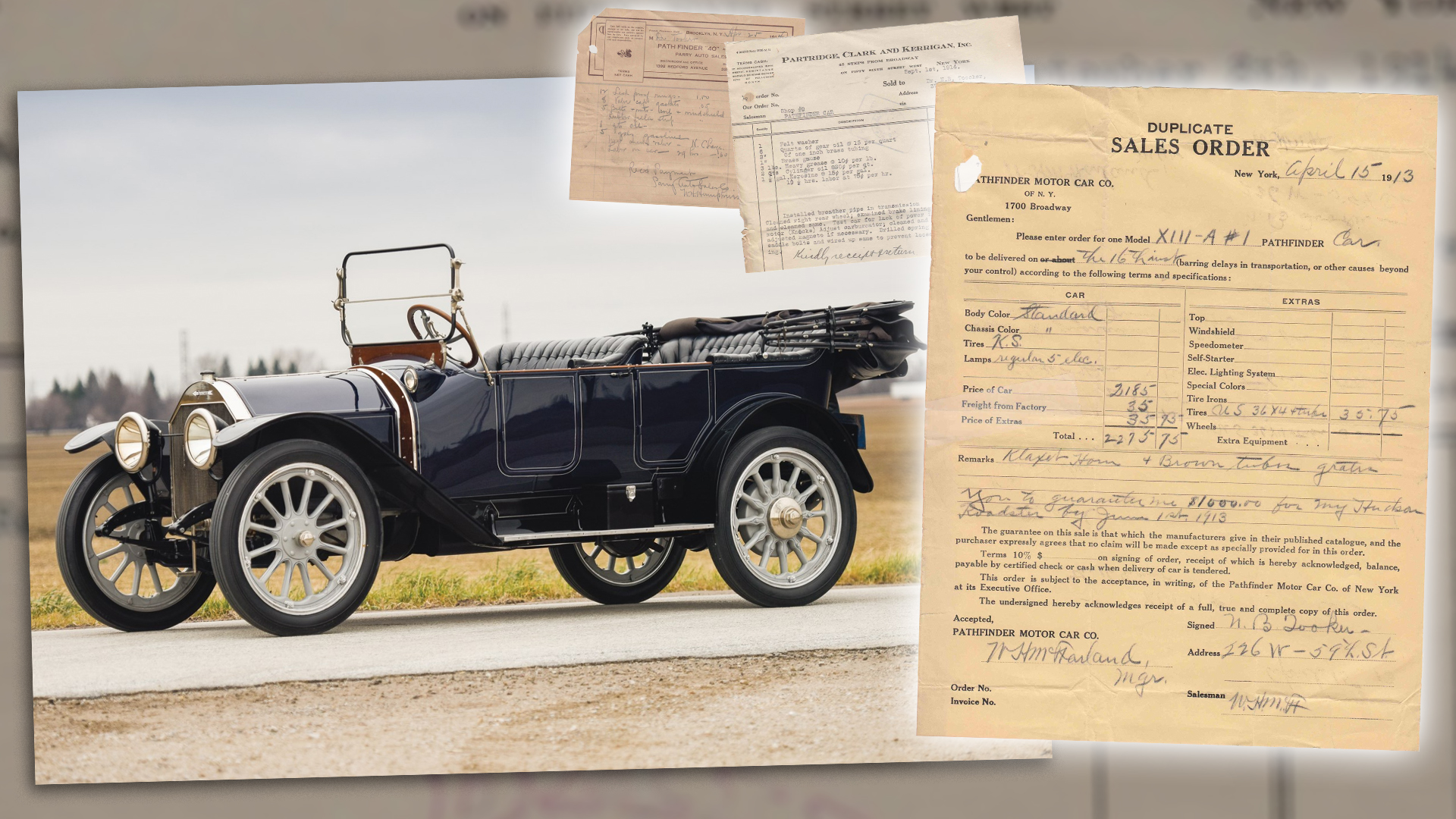

One of the earliest receipts is from buying a 1913 Pathfinder Series X111-A for $2,275.75 on April 15, 1913 in New York City, where Tooker lived. He would’ve been in his early 30s at the time, and adjusted for inflation, the car set him back over $58,000. Pathfinder Motor Car Company was birthed from the failed Parry Auto Company in 1912, and it was known for producing Brass-Era automobiles with superb reliability. It routinely tested itself with cross-country treks, similar to modern-day Cannonballers. But it only lasted until 1917 when World War I kneecapped Pathfinder’s chief market: Russia.

During his two-year stint with the Pathfinder, Dr. Tooker looked after it by getting the car serviced regularly. Work included leak-proof rings, new valve caps, belts, nuts, coils, oil, new shackle bolts, axle greasing, and felt washers. Labor for one receipt was 0.75 cents an hour, another was 0.60 cents. One routine maintenance bill was just $39.65, which still translates to $995.64 in today’s money.

In 1915, he traded in the Pathfinder for an $800 credit toward a new Franklin Motor Car Co. Touring Series 7 that ended up costing him a mere $1,375.00. It’s fascinating to imagine the transaction happening along the same broad contours as a trade-in at a dealership in 2019: a little wheeling and dealing before someone finally gives in. That company has an interesting history; Herbert H. Franklin started it in 1902, and unlike his competitors of the era, Franklin believed his cars should be air-cooled for better reliability and less weight.

It was actually known as “The Doctor’s Car” because its cold-weather reliability in a time before antifreeze made it popular with physicians responding to urgent calls in the winter. It was also one of the few vehicles available with comfortable four-corner full-elliptic springs. Makes sense that Dr. Tooker decided to trade up.

Early Franklins used wooden frames, later cars used steel and aluminum; its air-cooled six-cylinder engines were also made from aluminum, and for a time Franklin Motor Car Co. was the largest consumer of aluminum in the world. The company folded in the mid-1930s, and after World War II none other than Preston Tucker purchased the company to use Franklin’s later designs for a flat-six engine in the famous Tucker 48.

Tooker’s car enthusiasm really blossomed in with the Franklin Touring Series 7, as after purchasing the car the good doctor had it repainted, restriped, and upgraded a more accurate Stewart-Warner Speedometer—the company is still in business some 100 years later—which he paid $50 for.

As for how Tooker afforded two new cars in three years in the early 1910s, a time when most Americans still hadn’t even driven an automobile, his profession afforded him certain advantages.

“He worked for the government as a doctor in the War Department of Health and Training [through] the 1910s-20s. Money wasn’t a problem for him, from what I was told,” Tyler says. Along with the automotive receipts, Tyler said that a number of other athletic receipts—Tooker was a football player at Princeton—from the time period were also included in the wooden box. It was at the university in 1905 that he took part in one of the first public demonstrations of Jiu-Jitsu in America, sparring with the martial art’s founder Mitsuyo Maeda. Just a random fact to drive home that people used to be a lot more interesting.

Unfortunately, Tooker’s automotive story ends there, with just these now over hundred-year-old receipts to tell it and no one left with firsthand knowledge. “No one knows whatever happened to his prized cars,” says Tyler. “They were most likely sold prior to the ‘40s. Not many [people], if anyone, is around that would have met or known him.”

We’ll never know where the cars ended up, whether Tyler’s great-grandfather bought cooler pre-war or post-war cars, or if he wanted a rematch with Maeda. Like the lost Bugatti Atlantique, history has buried those answers. Yet, Dr. Tooker’s love affair lives on with the discovery of these receipts and we’re given the opportunity to peek at a very different era for car enthusiasm and the automotive industry. What else is waiting to be discovered?

Got a tip? Send us a note: tips@thedrive.com