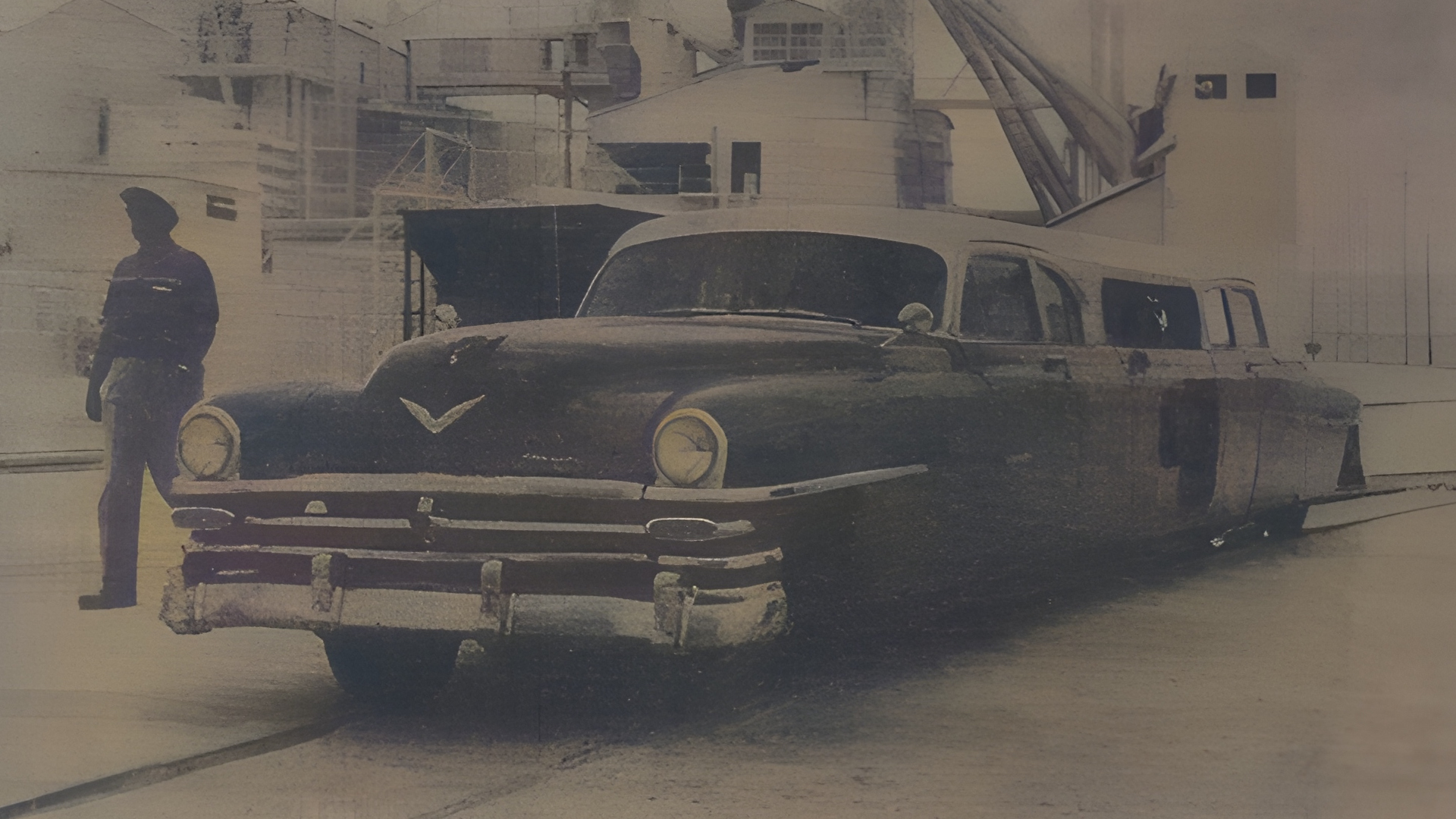

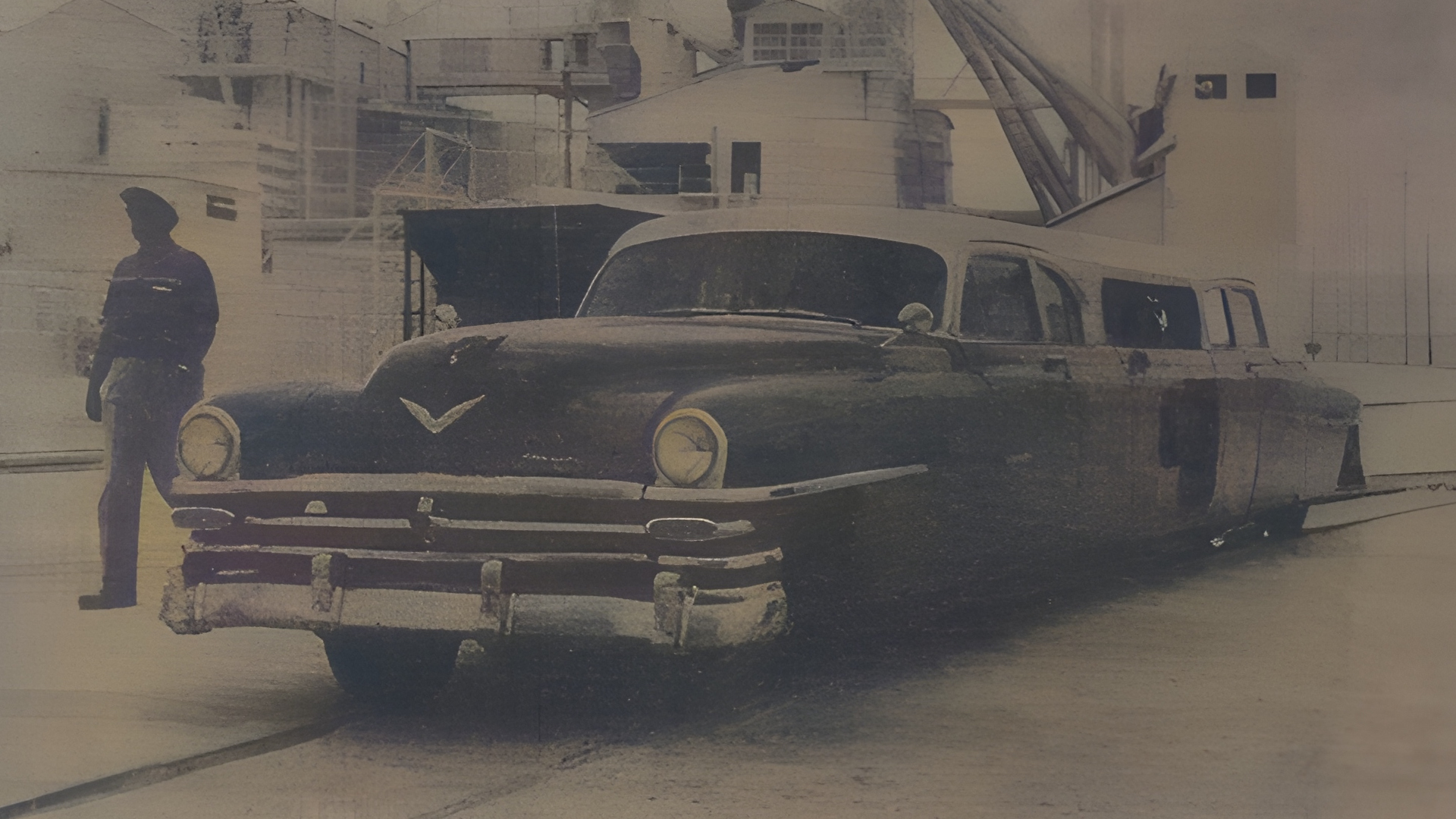

Late last year, I compiled the most complete account of an obscure historic rail vehicle known as the Blue Goose. This Chrysler-on-rails was a mining shuttle that by all accounts was too dang fast for its own good. Well, we didn’t know the half of it, because I’ve spoken to the son of the man that built it, and it turns out this bird flew a lot faster than we previously knew.

First though, let’s recap what we know about this hydra of a Chrysler. It’s a pair of 1953 Chrysler New Yorker Club Coupes that were joined at their rears to transport miners for U.S. Gypsum. Officially, the machine topped out at a respectable 40 mph, and was used for around 15 years before being retired—and either preserved or scrapped.

There were many gaps in its history though, such as details of its construction and true capabilities. I’ve since learned that some of the info from the limited sources available was inaccurate. This I know thanks to Phil Terry, son of Keith Terry, the man who designed the Blue Goose in the first place. Phil provided period newspaper clippings, a letter written by his father, and personal anecdotes to fill in otherwise lost details of the vehicle’s past.

Keith Terry was the head of plant engineering at U.S. Gypsum’s drywall facility at Plaster City, California where the Blue Goose originated. Daily operations during the mid-1950s required sending mining crews 26 miles to the gypsum quarry in the Fish Mountains in a fleet of Jeeps and trucks, which followed the railroad tracks used to haul down the rock. The desert environment was harsh though, and vehicles regularly became stuck in windblown sand, or got inhospitably hot in the summer.

At some point, USG realized it could eliminate these problems by just transporting its miners the way it moved material: on the rails. But because there were no off-the-shelf solutions to the problem, our buddy Keith was assigned to find a solution.

Keith started with the aforementioned Chryslers, for which he fabricated a frame from steel I-beams and C-channels. In its center was an early Chrysler Industrial Hemi engine, which I speculate to be an original 392. Power output was apparently double what was previously believed, or around 320 horsepower. That’d be a lot to put down for a mere 6,000-pound rail vehicle with conventional steel wheels, which is why the Blue Goose didn’t use such. Instead, Keith bought in custom-built flanged wheels that fit Michelin truck tires, keeping the Blue Goose on the rails while also improving traction.

As previously reported, it had dual cabins with their own separate sets of control. Together, they sat between 12 and 14 crewmen in relative comfort, with soft seating, a radio, and most importantly of all, air conditioning. Such luxury cost around $10,000 according to an article in the Imperial Valley Press, equivalent to about $111,000 today.

As of that article, which ran in 1956 or 1957, the Blue Goose wasn’t yet known by that name. As a miner remarked, “we have several names for it actually, but you wouldn’t be able to print them.” The reporter that got that line was taken for a ride by Keith, who pushed the vehicle to 80 mph. Keith seemed to later regret that, writing to the reporter’s father that he had promised plant management he wouldn’t take it above 60. But he did, and maybe much higher—past 100 mph, estimated using mileposts along the line.

In the end, speed was the Blue Goose’s undoing, as Phil Terry recalled.

“When the miners were returning home at the end of the day, they would get in a hurry and run it too fast through the curves on that narrow-gauge track,” Phil told me. “As a result, it derailed a couple of times, so USG decided to take it out of service.

“My dad took me for a ride several times. It was lots of fun for a little kid.”

Again, what happened to the bird after its grounding is unclear. One account says it was scrapped, another has it surviving until at least the early 2010s. Sadly, Phil Terry doesn’t know either. Perhaps someone who does will come forward, and share this strange machine’s fate. It’d be a delight to know it’s still out there, even if it’s been gathering dust for a decade. Still, the mystery lends this contraption another layer of mystique—on top of its unknowable true top speed.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: james@thedrive.com