Think all cars look more or less alike? Thank government for that, and then show a little gratitude, because that aesthetic uniformity has saved hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lives.

The same regulations that helped automotive-related deaths on American roads drop 40 percent from their 1970 levels have also bred a certin sameness. Car design, once a venue for wild personal expression, is now a game of variations on a theme. A combination of aerodynamics requirements, fuel-economy mandates, crash-test standards and even airbags and computer sensors have conspired to create anonymity on dealer lots. Add in bottom-line pressures from corporate taskmasters and you end up with a parade of beige, mass-produced envelopes that can expand or contract to fit two to seven people. Some have roofs, others don’t. Yawn.

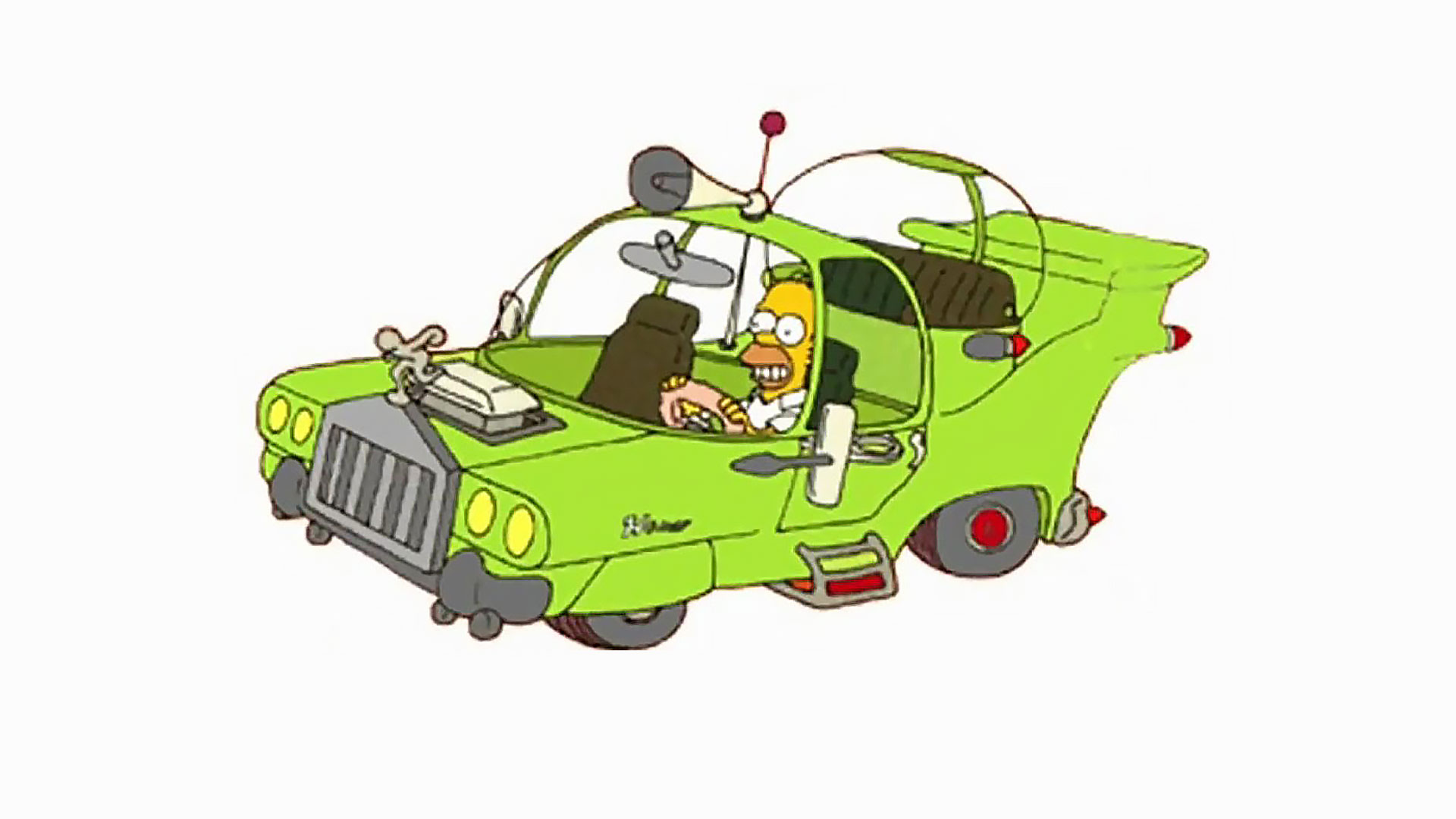

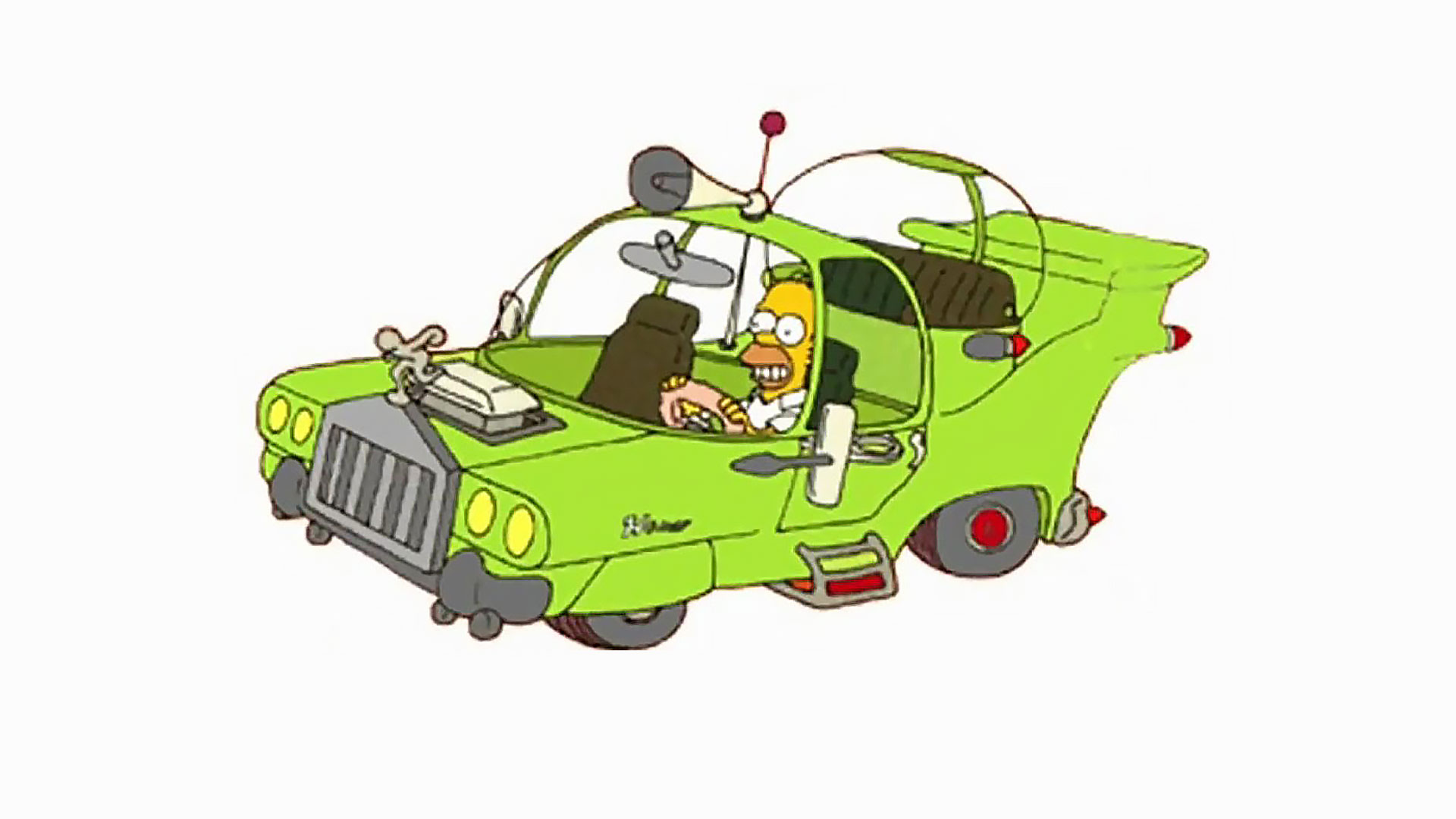

But what if a car designer answered to no one? Not a regulator, not an aerodynamicist, not a bean counter… nobody. Would tailfins make a comeback? How about boattail speedsters? What about Talbot-Lago’s famous Teardrop? Would the stylist go Google Car cute or custom-Jeep butch? Would we get The Homer?

The Drive caught up with Alfonso Albaisa, executive design director for Infiniti, to get his take on a pie-in-sky question.

“Not all production cars can be concept cars, but what really ties designer’s hands down is the cost of production of some of the more inventive vehicles,” he said at the 2016 Detroit Auto Show. “There are good and bad things about the situation that we have today. The cars are a lot of fun to design because they have so many more capabilities.”

RELATED: Infiniti Design Chief Alfonso Albaisa Cheats Death on the High Seas

Back-up cameras, parking sensors, navigation—these “black boxes,” as Albaisa calls them, take up space in the cabin and the body of the car, and designers have to work around them. From an aesthete’s perspective, they’re necessary evils. “Customers don’t care that we have to include all these sensors and the computers that process the information they gather, to make their systems work. They just want them to work, and be invisible,” he says.

Albaisa argues, however, that the premium market is getting some of its design flexibility—and differentiation—back. Some of that may come from a re-embracing of hand labor. “When I was at Nissan we designed the Murano completely on the computer and it came out well, but because I missed the days of clay modeling, everyone in the Infiniti studio now works with clay,” he says. “I brought it back because I just love the irregularity of the hand.”

There’s an appreciation for imperfection here that feels very… unregulated. “I’ve always been drawn to the more romantic vehicles out there,” Albaisa says as he begins sketching with a ballpoint pen. Broad, light strokes slowly appear on the blank sheet. “You know I knew designers who could use a wide-tipped marker and create the subtlest lines with them. When I graduated college I could finally do that,” he says as his hand glides across the page, shapes subtly coalescing into a form.

Albaisa moved to the Miami suburb of Coconut Grove as a young child after his family left Cuba. His father was an architect, and every day after school Albaisa would walk (or as he told it “run to avoid a giant Great Dane that lurked nearby”) to his father’s office to play until it was time to go home. “I would carve cars and boats out of balsa wood and put them in the Miami skyline model that my dad had in the lobby of his office building. I remember the way the leaves and the clouds filtered the sun. It was this big, glassed-in, coral entryway. My father used to discover the little toys I’d left there and yell at me for leaving them in his models.” As Albaisa tells it, one day in 1971, a black Jaguar E-type rumbled by, capturing his attention and his heart. “From that point on, I stopped carving boats and started drawing cars over and over and over. My dad was happy that he stopped finding toys in his models.”

As his hand moves faster over the drawing, Albaisa says he doesn’t know what’s guiding his wrist. He just lets it run.

“I’m still into the romanticism and the elegance of a car that drives by. That first time you see a car is magical. I don’t know why, we as humans are like that, but we react to beautiful movement. I love silhouettes that feel like they aren’t made by a machine. If we didn’t have the pressure of crash and economy and investment, I’d go back to a time when you could feel the fingerprint of the artist. A time when the signature of the car was its posture and its sound was its herald. In the future maybe we can go back to that, only this time, the car will roll silently by in hybrid, autonomous mode. Something beautiful that could go from a roaring tiger to a complete dove and still move people emotionally.”

Consider us moved.