Over the last few years cobalt has emerged as one of the most critical materials powering the shift to electric vehicles, and as automakers have announced ever-more ambitious EV plans the price of cobalt seemed likely to keep climbing indefinitely. Then, suddenly, something happened: between November of 2018 and February of 2019, the price of the rare metal dropped 40%. Since the beginning of February two major cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Glencore’s Mutanda and ERG’s Boss Mining, have laid off thousands of workers as the once-scorching cobalt market ground to a sudden halt. So what happened?

To find out, I rang up my friends and trusted advisors on all things battery supply chain-related, Benchmark Minerals. Benchmark’s cobalt maven Caspar Rawles patiently explained that something of a “perfect storm” has hit the cobalt market over the past year or so, some of which is specific to cobalt itself and some of which points to a more general cooling of the electric car battery arms race. “A whole load of factors have come together at the same time to create this weird market dynamic,” Rawles says. To understand this complex mix of factors, let’s quickly review some of the key characteristics of the cobalt supply chain and market.

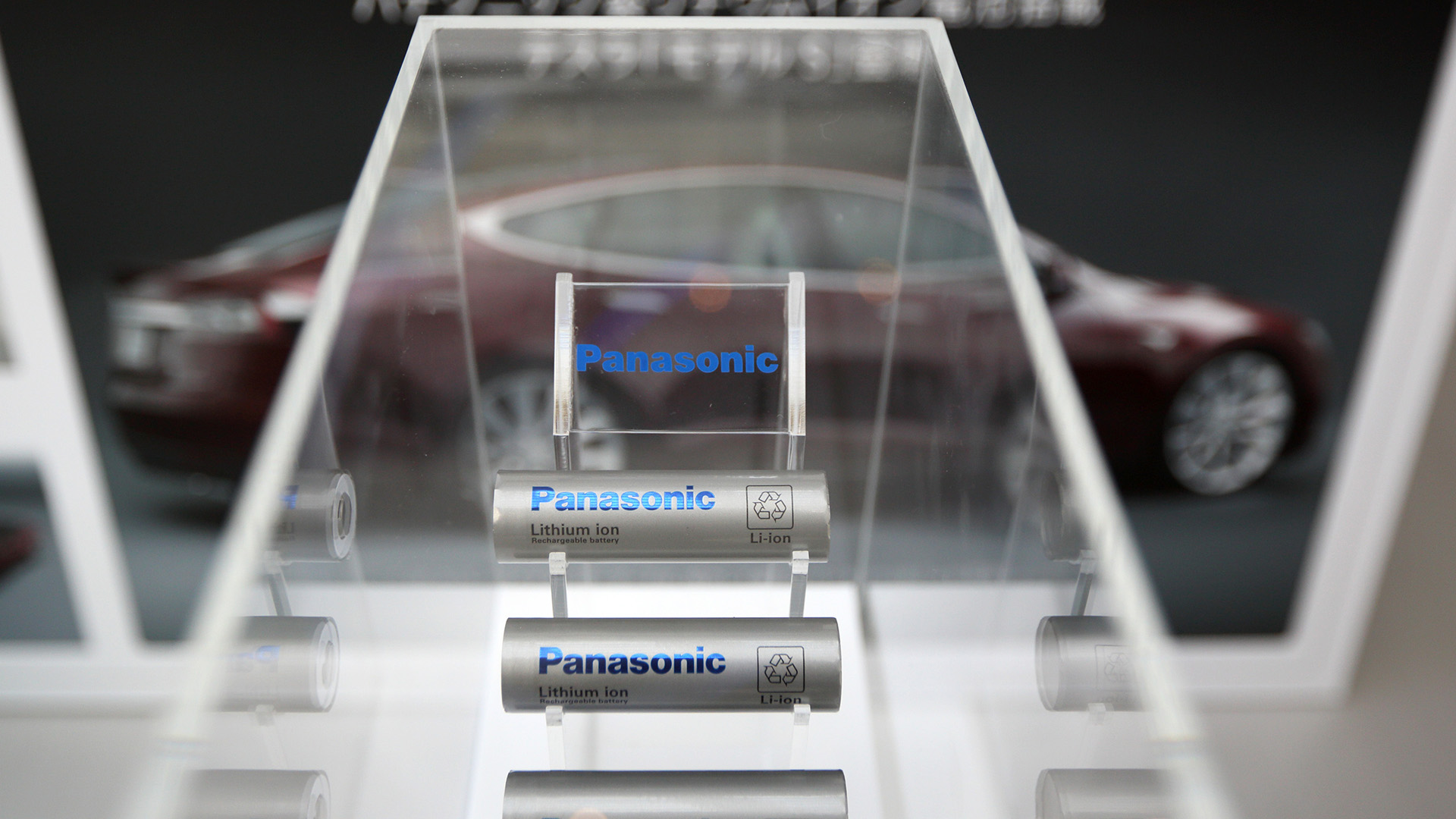

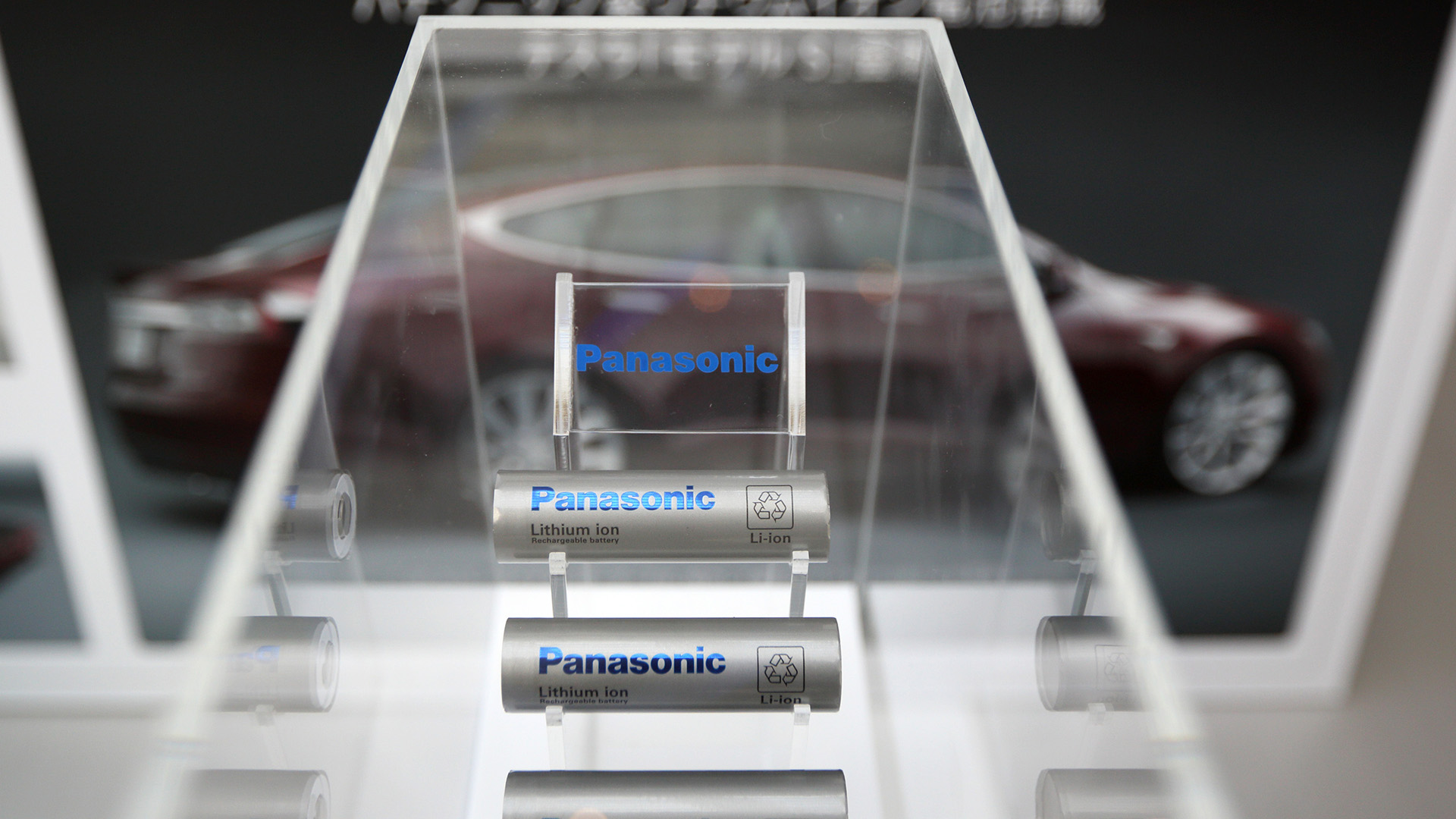

First, cobalt has traditionally been mined as a by-product of copper and nickel and as investments in electric vehicles has grown, demand for cobalt come up against limited supply. Used in lithium-ion battery cathodes, cobalt plays a crucial role in the high-performance cell chemistries used in EV batteries by stabilizing the cathode structure and allowing cells to be charged and discharged at higher rates without overheating or generating large amounts of oxygen which can create a fire risk. Cobalt is mined as ores and refined into a variety of products depending on the form it is mined in, including cobalt concentrate (a minimally processed 6-10% concentrate), cobalt hydroxide (a crystalline 20-40% feedstock produced by primary processing of ores, typically at the mine site), cobalt sulfate (a 20%+ refined product used in cell production), and cobalt metal (the traditional refined commodity) among others.

The cobalt market is heavily dependent on two countries: some 60% of the global cobalt supply (and growing) originates in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and almost all of it is manufactured into lithium-ion cells in China. This makes the cobalt market extremely sensitive to economic trends in China and political instability in the DRC, both of which have contributed heavily to the boom and resulting bust in the global cobalt market. The dramatic increase in electric car plans in response to rising regulatory requirements in China and Europe has also helped fuel the upward trajectory, and now the bear market suggests that the EV revolution may come more slowly than some anticipated.

Benchmark’s latest “megafactory” assessment, showing announced investments in factories with annual capacity of more than 1 GWh, makes cobalt’s bull run easy to understand. After modest expansions of 39 GWh and 31 GWh in 2014 and 2015, megafactory investments exploded with 149 GWh announced in 2016, 253 GWh in 2017 and a staggering 428.3 GWh in 2018. China is expected to hang onto its roughly 65% of megafactory capacity, but more importantly the processing supply chain that turns raw or minimally-processed cobalt into battery-grade materials is almost all located in China. These investments will create capacity of more than 1 TWh by 2028, requiring an increase in battery-grade cobalt supply from 50,000 tons per year currently to more than 200,000 tons per year.

According to Rawles, this boom in battery production investment and seemingly constrained supply caused a a lot of the typical symptoms of a commodity bubble in China. “When the prices were running up in 2017, there was an element of speculation that was helping drive the price,” Rawles says. “There was also a belief in China that demand would ride more quickly than was realistic. The Chinese were also buying more than they needed because they were stockpiling it and it was going up in value every month so they were making paper profits… which ended up being part of their undoing in 2018.”

During the 2017 China International Nickel & Cobalt Conference, where the coming year’s supply contract prices are negotiated, the Glencore dropped a bomb. The major player in DRC-sourced cobalt hydroxide boosted its asking price for the unrefined product from about 75% of the refined metal price to as much as 90%. With the price of cobalt metal and the percentage paid for hydroxide both going up, Chinese refiners also started to get hit by tightening credit and a wave of deleveraging. “Even though they were kind of making money on the face of it, in terms of what they had bought and processed themselves, the price was going up so quickly that when they went to buy more it was further out of reach” Rawles explains.

Meanwhile, Glencore was also about to create a massive new source of cobalt at its Katanga copper mine in the DRC, which had been halted since 2015 for a massive infrastructure and capacity-boosting project. Katanga was initially supposed to bring “in the mid to high teens” of thousands of tons of cobalt hydroxide annually, with a lifetime average of about 30,000 tons per year, significantly reducing pressure on tight global supplies. Another new mine, ERG’s RTR project, and a new refining plant, Chemaf’s Mutoshi plant, were both supposed to add an additional 15,000 tons per year to the DRC’s cobalt supply. “So you had this picture of 60,000 tons per year, theoretically, of cobalt coming onto the market in 2019,” Rawles says.

This combination of unsustainably high prices and massive new supplies could only spell one outcome. “At the end of Q1 2018, you saw sentiment turn in China,” Rawles says. “Everyone said ‘production’s not ramping up as we thought, we don’t think EVs are going to happen as quickly, we can’t by the cobalt, we’re losing money.’ All of a sudden it went from everybody buying maximum volumes to people just starting to consume domestic stocks and inventories and buy pretty much nothing from the miners.”

But, Rawles cautions, actual demand for cobalt hasn’t gone away. In fact, Benchmark saw demand rising between 10 and 15 percent between 2017 and 2018. He also says the push toward low-cobalt battery chemistries, like the so-called NMC 8-1-1 (named for its cathode composition of 80% nickel, 10% manganese and 10% cobalt), has “subsided” over the past year due to technical challenges and safety concerns, as well as low cobalt prices. The lower prices may actually be an opportunity for automakers to lock in favorable prices long-term, helping improve the razor-thin (at best) margins on electric vehicles. Even so, Rawles says there is likely to be consolidation in the Chinese battery supply chain as well as bankruptcies of smaller players, driven by high R&D costs to keep pace with cell quality and production process improvements and government policy aimed at weeding out weaker firms.

Volatility in cobalt prices is also unlikely to go away. Glencore announced a $5.6 billion restructuring of Katanga last year, it is under investigation by the US Department of Justice, and has already paid $20 million in fines in Canada for failures to disclose related risks and seen individual officers fined as well. A new mining code backed by then-president Laurent Kabila raised taxes on cobalt from 3% to 5%, and the new president Felix Tshisekedi, who was elected in December, is still seen by miners as an unknown quantity. Meanwhile, Katanga’s planned 30,000 tons per year still hasn’t arrived and cobalt operations there were halted in November due to uranium contamination… or possibly annual supply contract negotiations.

Even with low prices for the moment, the persistent corruption and human rights issues in the DRC and aggressive moves by major players like Glencore have some in the auto industry continuing to look for a way out of cobalt dependence. “Cobalt is still a gotcha,” said Micheal Austin, VP of BYD North America at last November’s Benchmark Minerals Week. “Realize that cobalt is cocaine right now and there’s a new cartel forming.”