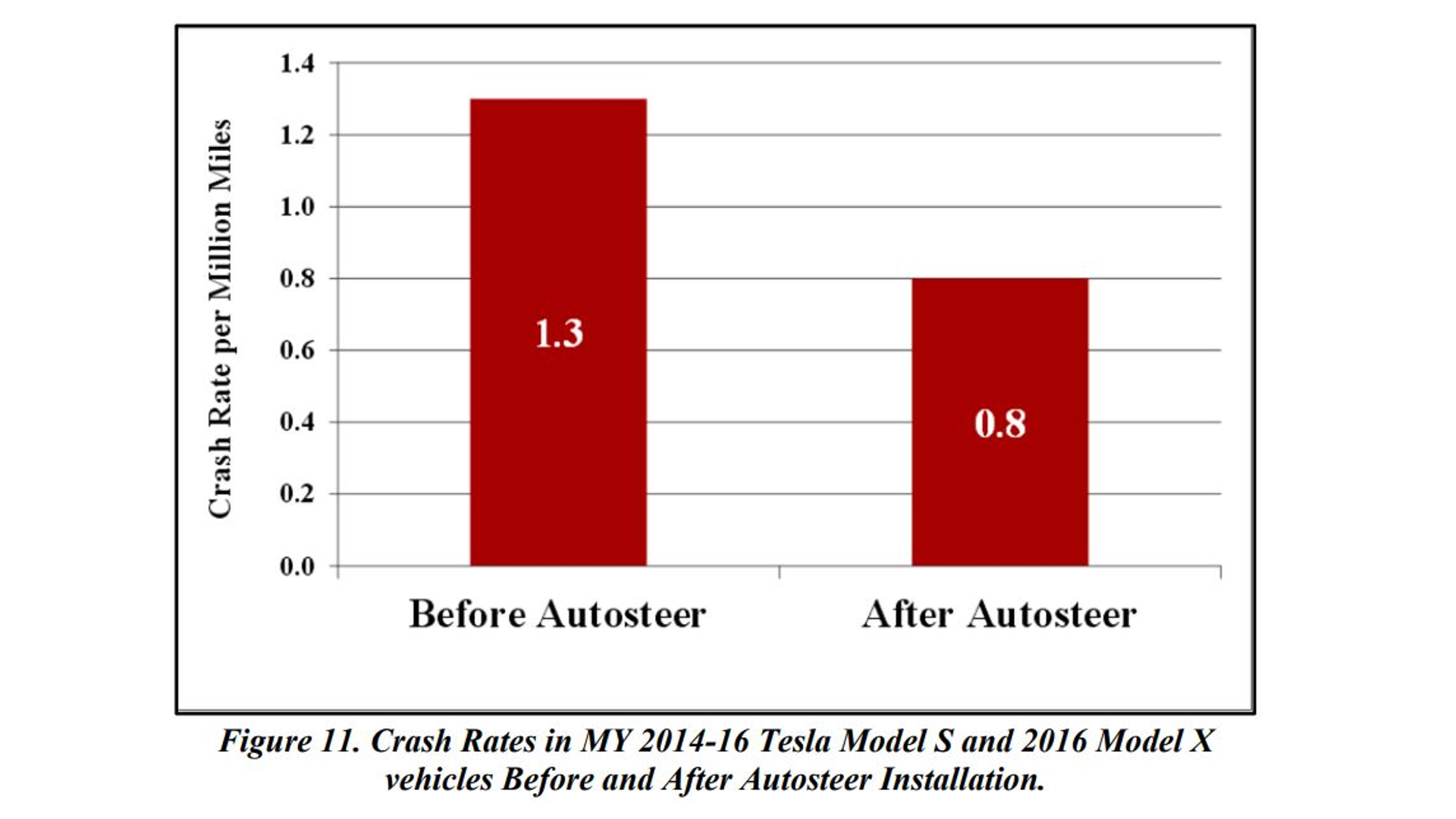

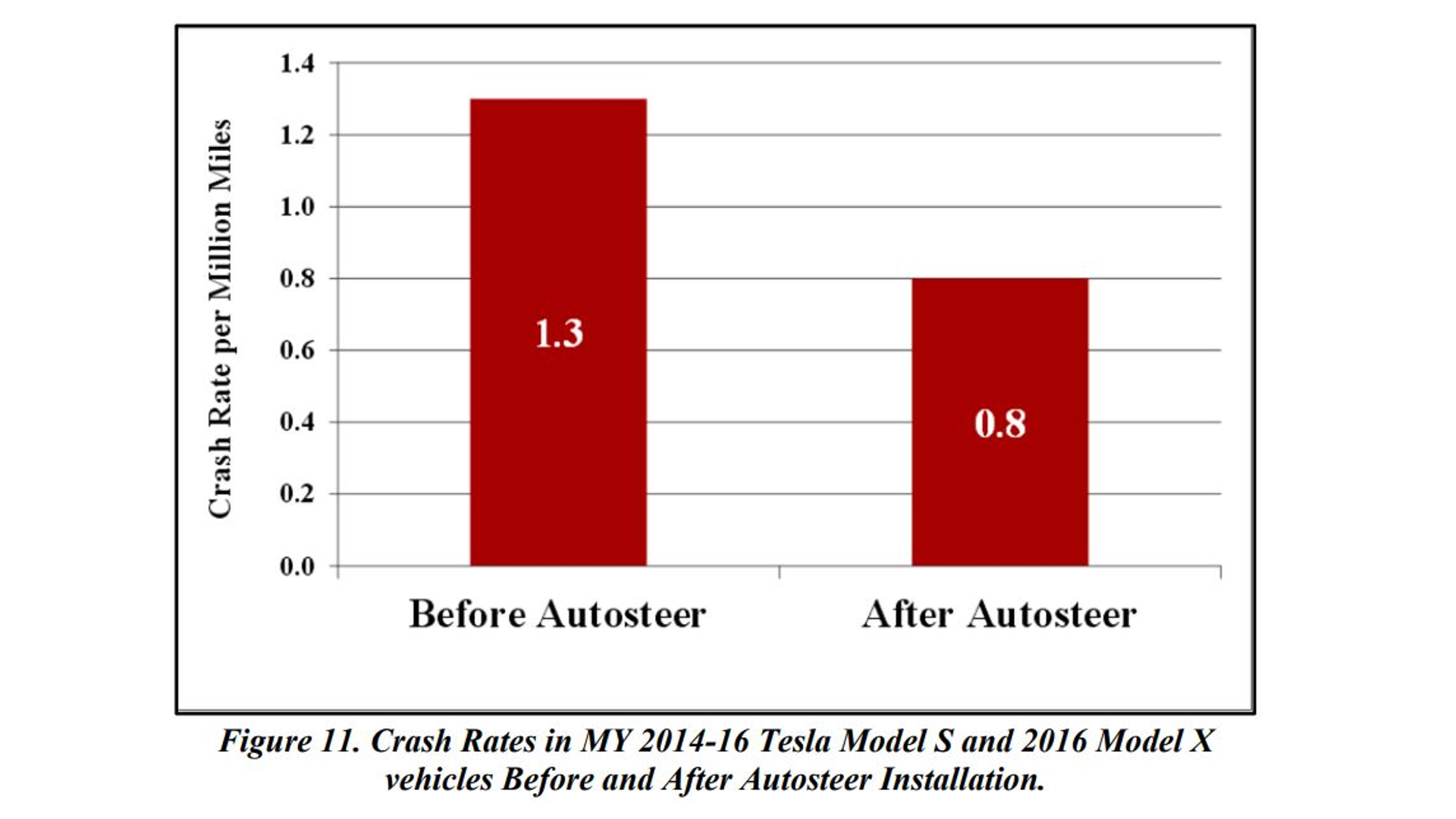

Two years ago, mounting concerns about the safety of Tesla’s Autopilot system were reaching a peak. In the wake of the fatal Josh Brown crash, in which a Model S drove directly into a truck at high speed while on Autopilot, serious questions were being asked about the design and marketing of a system whose hands-free operation blurred perceptions of the line between autonomous drive and driver assistance systems. Then, on the last full day of the Obama Administration, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) came out with a report [PDF] that claimed that “the Tesla vehicles crash rate dropped by almost 40 percent after Autosteer installation.” With that one finding, NHTSA singlehandedly dismissed the public’s concerns about Autopilot and eliminated any momentum toward regulatory action.

I was immediately skeptical of NHTSA’s finding since it did not seem to control for the effects of Automated Emergency Braking (AEB) and Forward Collision Warning (FCW), which the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) had found to reduce frontal collisions by 40%. Randy Whitfield, of company called Quality Control Systems, had questions of his own about NHTSA’s Autopilot study, and submitted a FOIA request for the underlying data which was denied. Whitfield sued the agency in response, and in November of 2018 NHTSA finally released the data. Now, thanks to Whitfield’s legal wranglings and subsequent analysis [PDF], we know that NHTSA’s finding was based on bad data and worse analysis. The 40% crash reduction claim that Tesla has repeatedly used to defend itself, after subsequent fatal Autopilot crashes, has now been definitively debunked.

This situation raises a number of questions, each more disturbing than the next, and many of which we still don’t have the answers to. While we work to obtain answers to some of the broader questions, we can at least explain how NHTSA got this analysis so badly wrong.

During Whitfield’s FOIA lawsuit, NHTSA revealed that it had sent an information request letter to Tesla in the course of investigating the Josh Brown crash. NHTSA had asked Tesla for “The

mileage Autosteer software was installed on the vehicle,” in response to which Tesla sent data documenting “Previous Mileage before Autosteer Install” and the “Next Mileage after Autosteer Install” as well as data for airbag activated crashes. This was the data that NHTSA used to obtain its 40% crash reduction finding, in a process the agency describes as “examining the sums of the miles driven prior to Autosteer activation, miles driven after Autosteer activation, airbag deployment events prior to Autosteer activation and airbag deployment events after Autosteer activation for all of the subject vehicles.”

What Whitfield found was that only 5,714 vehicles of the 43,781 vehicles studied actually had full, verifiable data that could support NHTSA’s findings. When Whitfield performed the same analysis that NHTSA had on this cohort for which complete mileage data before and after Autosteer installation was available, he found that it pointed to a 59% increase in airbag deployment after Autosteer was installed. Even then, without knowing the exact mileage at which the airbag-deploying crash took place makes it difficult to come up with specific data about the relative safety of the system. But, using statistical regression, Whitfield determined that the installation of Autosteer was not associated with a decreased risk of an airbag deployment crash, when controlling for exposure mileage. His analysis actually found that “Autosteer is actually associated with an increase in the odds ratio of airbag deployment by more than a factor of 2.4.”

According to Whitfield’s analysis, NHTSA seems to have applied a separate calculation of exposure mileage for the 14,791 vehicles where “Previous Mileage before Autosteer Install” and the “Next Mileage after Autosteer Install” were both unreported. He shows that all the mileage for these vehicles is applied to “Next Mileage after Autosteer Install” but that three airbag deployments were counted before Autosteer was installed, fundamentally skewing the data in favor of finding a reduction in post-Autosteer installation crashes.

When Whitfield looked at the 8,881 vehicles for which there was a gap between the “Previous Mileage before Autosteer Install” and the “Next Mileage after Autosteer Install” he found that the gap was 2.6 times as large as the total exposure mileage before Autosteer installation and eight percent smaller than post-Autosteer installation mileage. By comparing this gap with the cumulative mileage before and after Autosteer installation,he found evidence that there had been “a considerable undercount of actual exposure mileage before Autosteer installation” resulting in “a differential bias that inflates the calculated crash risk ‘before Autosteer’ to a greater degree than the calculated risk ‘after Autosteer.’”

When Whitfield looked at the 14,260 vehicles where the exact mileage at Autosteer installation wasn’t reported, but “Next Mileage after Autosteer Install” was reported, he found that NHTSA included no exposure miles at all in the crash rate calculation even though there were 15 airbag deployments for those zero miles. Obviously counting 15 deployments over zero miles for nearly a third of the entire population studied fundamentally threw off the ultimate crash rate in a way that made it more likely to find a post-install reduction.

Ultimately, Whitfield convincingly demonstrates that NHTSA’s analysis is fundamentally flawed in ways that made a favorable finding for Tesla more likely. Though its statistical regression on the small group of vehicles for which the data is complete suggests that airbag-deploying crashes go up after Autosteer is installed, the small size of that sample and and questions about the overall accuracy of the dataset hardly make it definitive. Because vehicles are taken off the road after airbag deployment, the impact of systems like AEB and FCW weren’t controlled for, and some vehicles may have been scrapped before Autopilot became available, he concludes that this data “is not necessarily the best choice on which to stake a risk analysis about Autosteer.”

But, as Whitfield notes in the conclusion, the most disturbing aspect of this situation is the amount of “resources both NHTSA and Tesla were willing to commit to prevent public scrutiny… based on a fear of competitive harm to Tesla. NHTSA was never transparent about either the methodology it used to obtain its 40% reduction finding, or the data underlying it, and if Whitfield hadn’t tenaciously persisted in suing NHTSA the truth might never have come to light. This raises a fundamental question that NHTSA must answer: why was it more concerned about competitive harm to Tesla than it was about transparency to the public whose taxes provide its budget, and whom it ostensibly serves? Without addressing that question, we will never know whether NHTSA was simply incompetent in this instance, or if it (or one or more of its staffers) actually colluded with Tesla to present misleading data about Autopilot safety.

We know that Tesla repeatedly puts out

easily-debunked statistics and conceals its data in a system with as little transparency and accountability as possible, in an attempt to make Autopilot seem safe. We also know that Tesla originally called Autosteer a “convenience feature” and only started presenting it as a “safety feature” around the time of the Josh Brown crash. If NHTSA wasn’t aware of Tesla’s repeated attempts to manipulate public perceptions of Autopilot using bad statistics, it should have been.

Whitfield notes that this revelation has not prompted NHTSA to re-open any investigation into Autopilot, which implies that the agency is still stonewalling. Given that the NTSB investigation into the same Josh Brown crash concluded that Autopilot had two fundamental design issues which contributed to Brown’s death, the lack of sufficient driver attention monitoring and the lack of hard operational design domain limits, NHTSA’s combination of inaction and what can at its most generously be called incompetence, is especially galling.

Regulating automated driving systems is not easy, and there is no doubt that mistakes have been and will continue to be made. But ignoring thorough investigations like NTSB’s, engaging in worthless and misleading studies like the “40%” analysis and working to prevent transparency around such findings collectively constitute a state of affairs that can only be described as a crisis.

NHTSA, or its Inspector General, needs to not only provide answers about what happened here, it needs to take concrete steps to rebuild public trust. The issue of automated driving safety is too important for anything less.