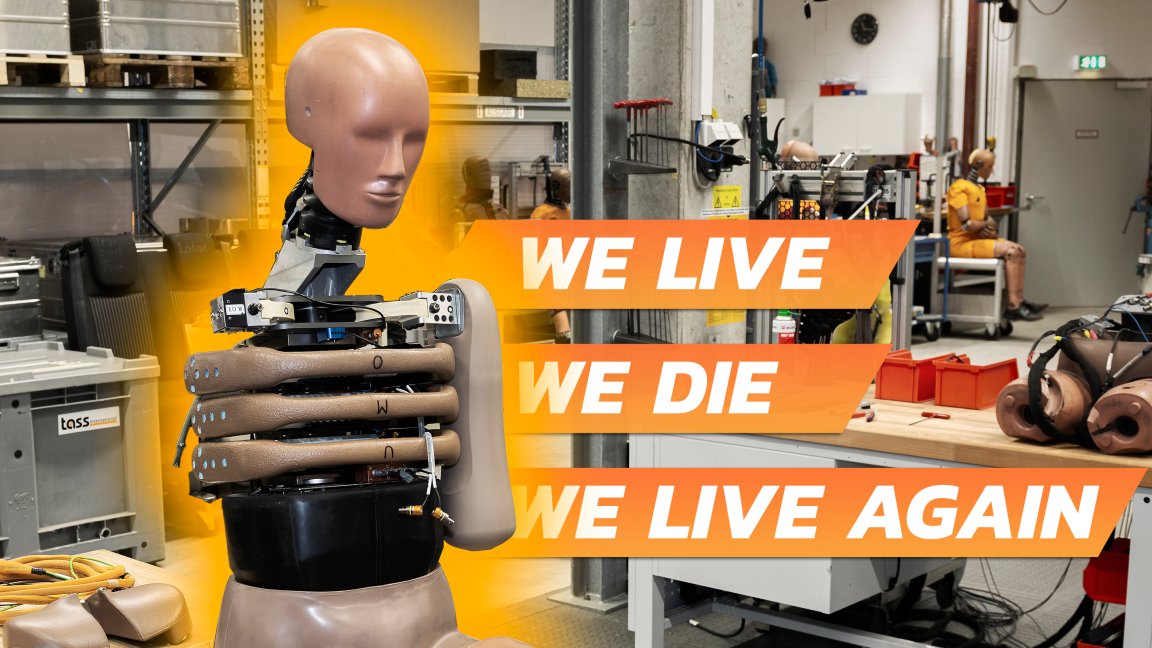

The first season of Westworld had scenes in a high-tech basement where humanoid robots were repaired after being “killed.” It was pretty cool, and a little creepy. Believe it or not, the crash-test dummy lab at Magna’s cavernous R&D facility in Sailauf, Germany looks very similar. Less sinister, though… unless you’re a million-dollar mannequin marked for death.

Some of Magna’s crash test dummies are, in fact, worth over a million bucks. And if you want to be fancy, you can call them Anthropomorphic Test Devices (but we won’t). Dummy or ATD, there’s a lot more to these human-shaped data-gathering tools than floppy arms and caution tape stripes. We got the opportunity to step into the company’s crash lab during a tour recently, and now you get the rare chance to peek inside the respawn point for the same crash dummies that have validated countless cars for crashworthiness.

Magna is not a name brand that casual car appreciators will necessarily know, but it’s one of the most prolific in the biz. It’s what’s known as a tier-one supplier; it performs a huge range of functions for car companies you do know and drive.

For example, Magna currently conducts the manufacture of the BMW Z4 and Toyota Supra, Mercedes G-Class, some Minis, some Jaguars, EV batteries, supercar transmissions, gasoline engines, cameras and collision-warning sensors, and more. The company also performs its own research and development of car parts, manages supply chains, and does a great deal of validation for cars at various stages of development, among other things.

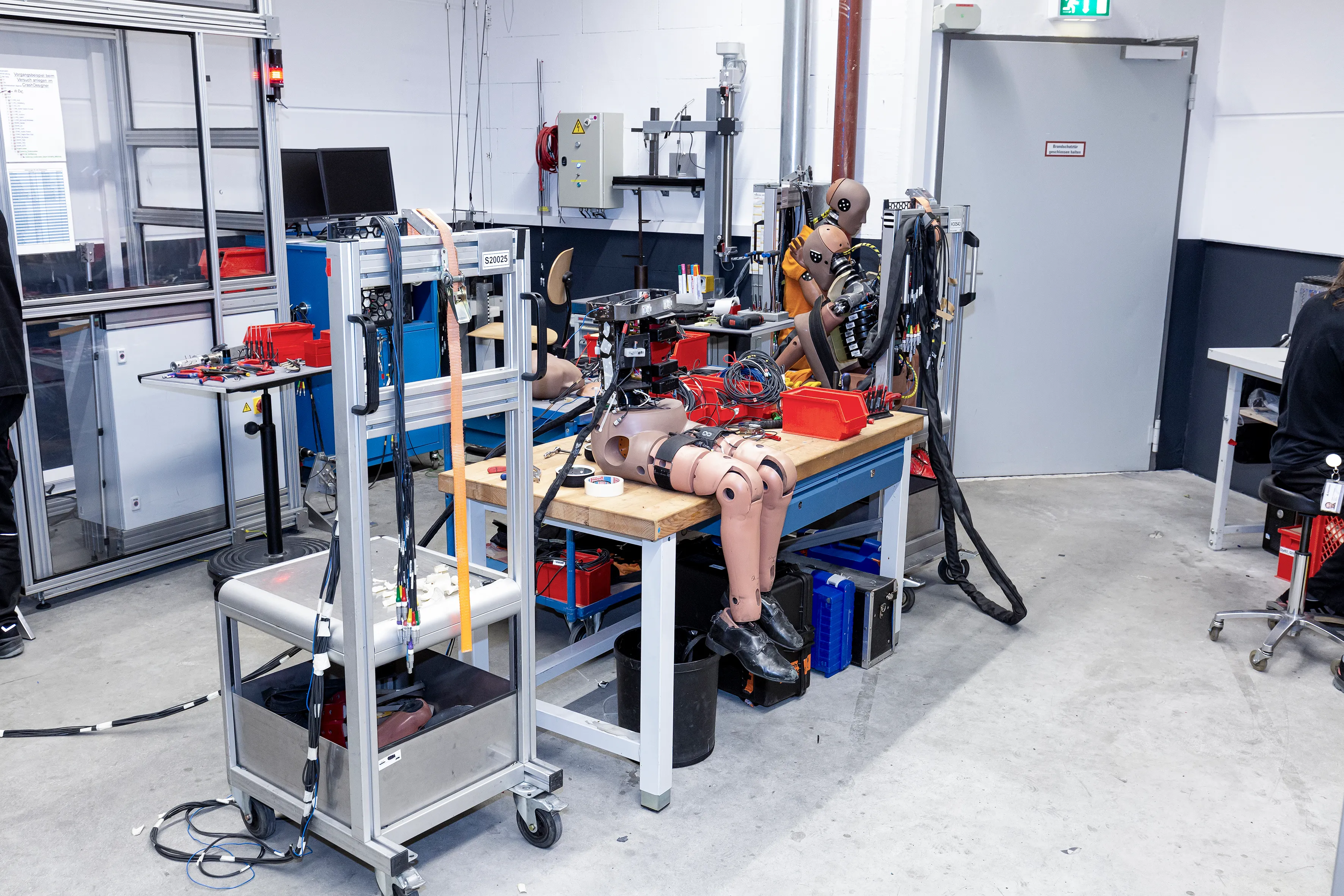

Crash testing is, of course, a critical part of that validation. And in a few huge buildings around Sailauf, which is sort of in the lower-middle area on a map of Germany, Magna does that by throwing cars at walls, ramming spikes through EV batteries, and torturing these heavily computerized dummies to determine how safe (or not) vehicles are.

Technically the outfit doing this testing is ACTS GmbH & Co. KG, (stands for “Advanced Car Technology Systems”), which is a subsidiary of Magna. Regardless, a lot of cars and crash dummies are smashed here in the name of science and safety. The crew at the lab told me it typically runs 600 dummy-crewed crash tests a year, which apparently translates to about 3,200 injury events for Magna’s dummies in the same amount of time.

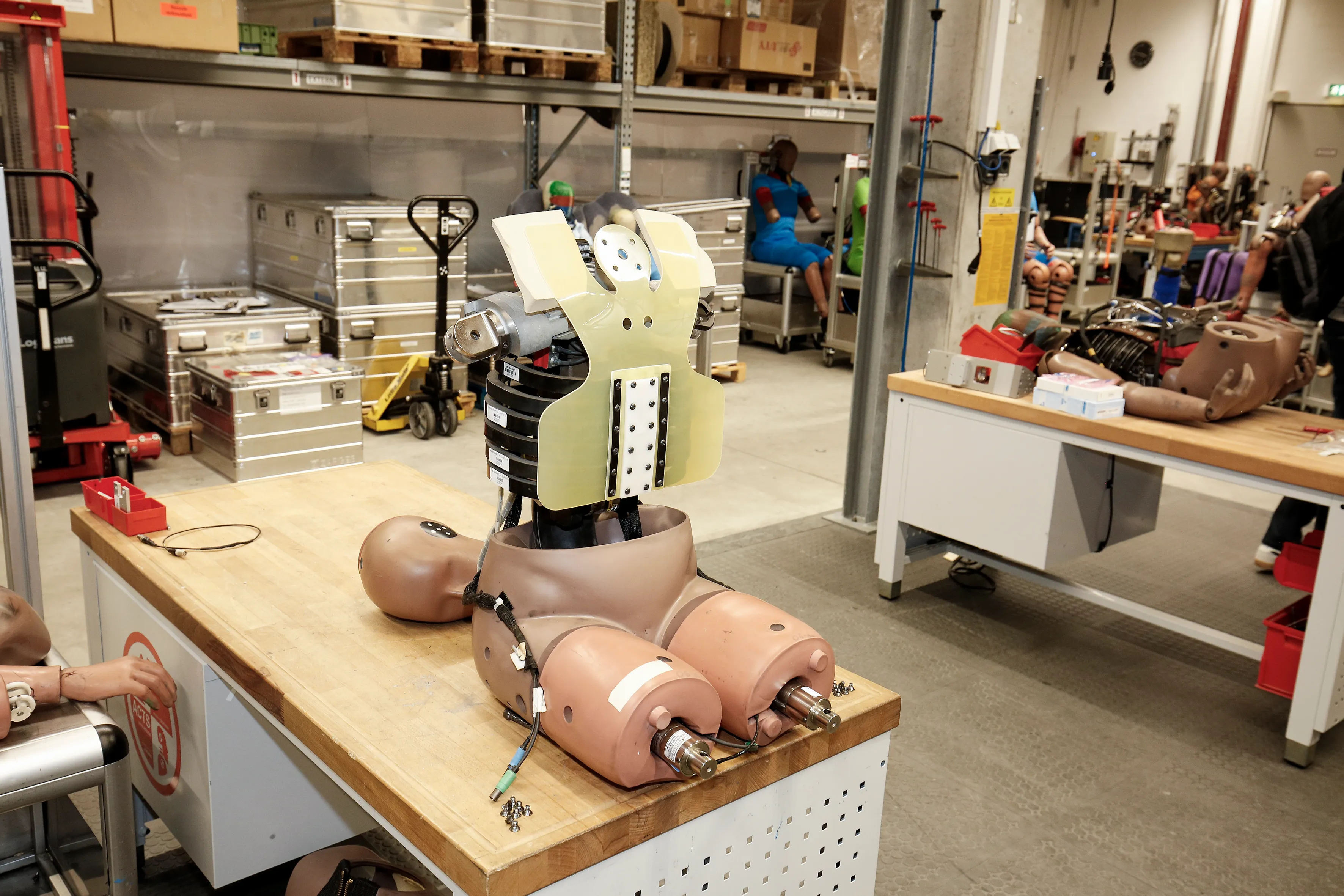

There were 25 dummies on the duty roster at Sailauf when I was down there, including simulated men, women, children, and some specialty pieces like standalone torsos and legs to measure the effects of injuries in specific scenarios. No pets yet, though.

For babies, I was interested to see what type of car seat is considered the gold standard. But as it turns out there’s no such unit—we were told that OEMs prescribe what baby seats should be crash-tested for youngsters. So if you’re curious on what seat your car’s maker recommends, check your owner’s manual, ask the parts desk at a dealership, or try Googling around with your year-make-model.

In some instances of crash research, human cadavers have been employed. I was grateful that that wasn’t the case at this facility, though. I don’t consider myself particularly squeamish but I would not be in a rush to look at actual bodies being deconstructed by vehicles colliding with concrete.

While a once-warm body would provide, er, visceral information on the effects of a crash, Magna’s dummies are a lot more effective at quantifying and recording their traumatic experiences.

Magna’s people said that crash dummies as we know them came into use in the 1960s. The ones in use at Sailauf today would be considered the “third-gen” of their design. And while several outfits make these dummies, it’s governments that set the crash-measurement standards to which they’re built.

One particularly weird-looking one—really the only dummy that didn’t look at least partially human—was a girthy column. It’s called a legform, so you can probably guess what it’s designed to simulate. It’s more than just a leg, though. With a raft of impact sensors between its “foot” and “pelvis,” it’s made to measure how much it’d hurt to be run into by a car.

Magna does two main tests with such a device to study pedestrian safety. The legform is tossed at the hood from a specific angle, and of course, it’s hit with a bumper.

The staff wheeled out an adult dummy that had been built in 2022. We were told it cost 800,000 euros before any sensors were mounted up to it. The raft of small speedometers and gyroscopes and accelerometers and other such things allows it to record 160 channels of activity (speed, force, ect) in a crash. Another tech said a full-sized dummy, as equipped, would be about 1,200,000 euros.

Dummies are rebuilt and recalibrated after every crash, and typically rebuilt completely after 10 to 20 accidents, depending on how rough of a life it’s had. One of Magna’s techs told me that the dummies could essentially live forever since they’re so modular and are rebuilt so often. You get into a Ship of Theseus situation pretty quickly when you start trying to calculate a crash-test dummy’s lifespan, though.

Quick aside for those of you who didn’t have a Greek mythology class or remember that one scene from that Avengers movie: Theseus was a guy with a ship, and like most of my cars, that ship was repaired so many times that, eventually, it had none of the original parts it left the factory with. So “Theseus’ Paradox” asks: Is it still the same ship, or is it now a new ship?

While scratching my head at that one and thinking about the War Boys chat from Fury Road (“We live! We die! We live again!”) I asked one of the technicians how much damage had been done to the humanoid torso he had partially dissected on his workbench. He kind of laughed and shrugged, gestured to a spiderweb of strange-looking materials, and essentially said that no single part on the desk was “under 1,000 euros.” Ouch indeed!

And of course, it’s not just bodies that have to be tested for crashworthiness—it’s the cars themselves, and more recently, EV batteries.

Magna’s main car-crashing lab at Sailauf looks like a spaceport from science fiction. A cold, concrete stadium-sized venue with colossal doors, intimidatingly strong robotic armatures, and intense lights is where cars are chucked into barriers at various angles, to be studied in slow-motion while somebody sweeps up broken glass.

The central “crash block,” a 100-ton monolith that has killed countless cars, rests in the middle of the room surrounded by cameras. As cars bounce off it, the results are recorded at a rate of 5,000 frames per second. That gives engineers a very precise look at exactly what happens to their vehicle design at every stage of its demise. Sadly, I wasn’t allowed to get any pictures of it.

Electric cars present one particularly interesting new factor in crash safety: The giant battery slung under the passengers. While EVs get smashed and crashed into the kill block like everything else, EV batteries are currently being torture-tested on their own too.

Magna runs a range of tests on batteries, including 10,000 power cycles and simulations of years of use. Batteries are crushed by immensely powerful squeezers with 250 kilonewtons, or more than 50,000 pounds of force for observation. But the most exciting battery crucible is what’s referred to as “the nail test.” In the nail test, an EV battery is placed into a special containment box and spiked with a 6-millimeter nail. That forces the battery to short-circuit, and inevitably, catch fire. Engineers watch this process through a protected camera and take notes.

One of Magna’s people mentioned that the burn rate of EV batteries was inconsistent. I guess running the same test with the same battery sometimes yielded a quick fire while other times it took longer. I suppose that’s why these situations are still being studied.

We weren’t allowed to take many pictures, because a few prototype items from OEMs were in various states of dismantlement around the facility. But I can show one last interesting detail from my trip to Magna’s Sailauf facilities: Its EV battery fire exhaust system.

A big battery burning makes a lot of noxious smoke, and that’s got to go somewhere. Before it makes it to the atmosphere, emissions from a battery burn go through water, like a bong, and then are washed again through a charcoal filter. The exhaust rig looked like it might have taken up as much square footage as the burn box itself.

Unfortunately, that’s all I can really share about Magna’s safety and crash-testing operation in Bavaria. Working with multiple, sometimes rival, automakers and developing numerous prototypes requires a high level of security and vagueness in answers to questions about future vehicles.

However, I did come away with an elevated appreciation for the complexity of crash testing. The crash dummies I met weren’t quite as charismatic as Vince and Larry, but I’m glad there are good robots going to work at the smash factory day in and day out to help make our cars safer.