“Working at Motorola in the 1990s was like working at Google today,” said Chris Pratt, the software engineer who worked on the company’s secret electric Chevy Corvette conversion at the time. Today, it can be hard to picture just how powerful Motorola was at the close of the 20th century. The telecommunications giant built the radio Neil Armstrong took to the moon, developed the microprocessors that helped make personal computers possible, and literally invented the cell phone.

In short, it made things that changed the world—and it could’ve done so one more time.

[Editor’s note: This is Part II of a three-part series laying out the never-before-told story of Motorola’s amazing electric Corvette project. Part I can be found here, and Part III is here.]

All the former Motorola employees I interviewed spoke highly of the company’s wealth of talent in the early 1990s and the incredible experience of being at the center of it all. The original story of the electric Corvette’s rediscovery last year went viral among Motorola alumni, bringing back fond memories of sunnier days. Employees past and present reminisced on the life, times, and outlandish projects that the company was constantly working on, projects that are slowly getting lost to time and the ever-looming threat of internet link rot.

Motorola’s attempt to build an electric sports car, a project so secret only a handful of employees outside the core team knew it existed, was just one of many big ideas being tested out back then. But when you think about what could’ve happened—with the auto industry, with the planet—if Motorola realized the promise of the EV Corvette and threw its considerable resources at leading the way on electric cars, the what-ifs are almost overwhelming.

Back in 1993, after years of plotting their move, Motorola engineers Sanjar Ghaem and Ken Gerbetz successfully convinced upper management to give them $25,000 to build an electric car. It was ostensibly to be a showcase for various Motorola technologies, though in the backs of the minds, they knew this was a rare chance to prove EVs could work at a place with the means to do something about it. As technology director for the Motorola Automotive group, Ghaem handpicked a team of professional tinkerers and dreamers at the company to work on it: engineers Bob Gerbetz (Ken’s brother), Chris Pratt, and Edward Li.

And the head honchos were also intrigued by the EX-11, the electric race car Ghaem and the Gerbetz brothers had created to prove the viability of the concept. Built for pocket change on a compressed timeline with limited manpower, the car beat Toyota, upset GM, and threw in a new EV top speed record for good measure at an exhibition race that year. Money was unlocked for a follow-up for that one too, and now it was time for this skunkworks crew to see what they could do.

The Electric Corvette and the EX-12

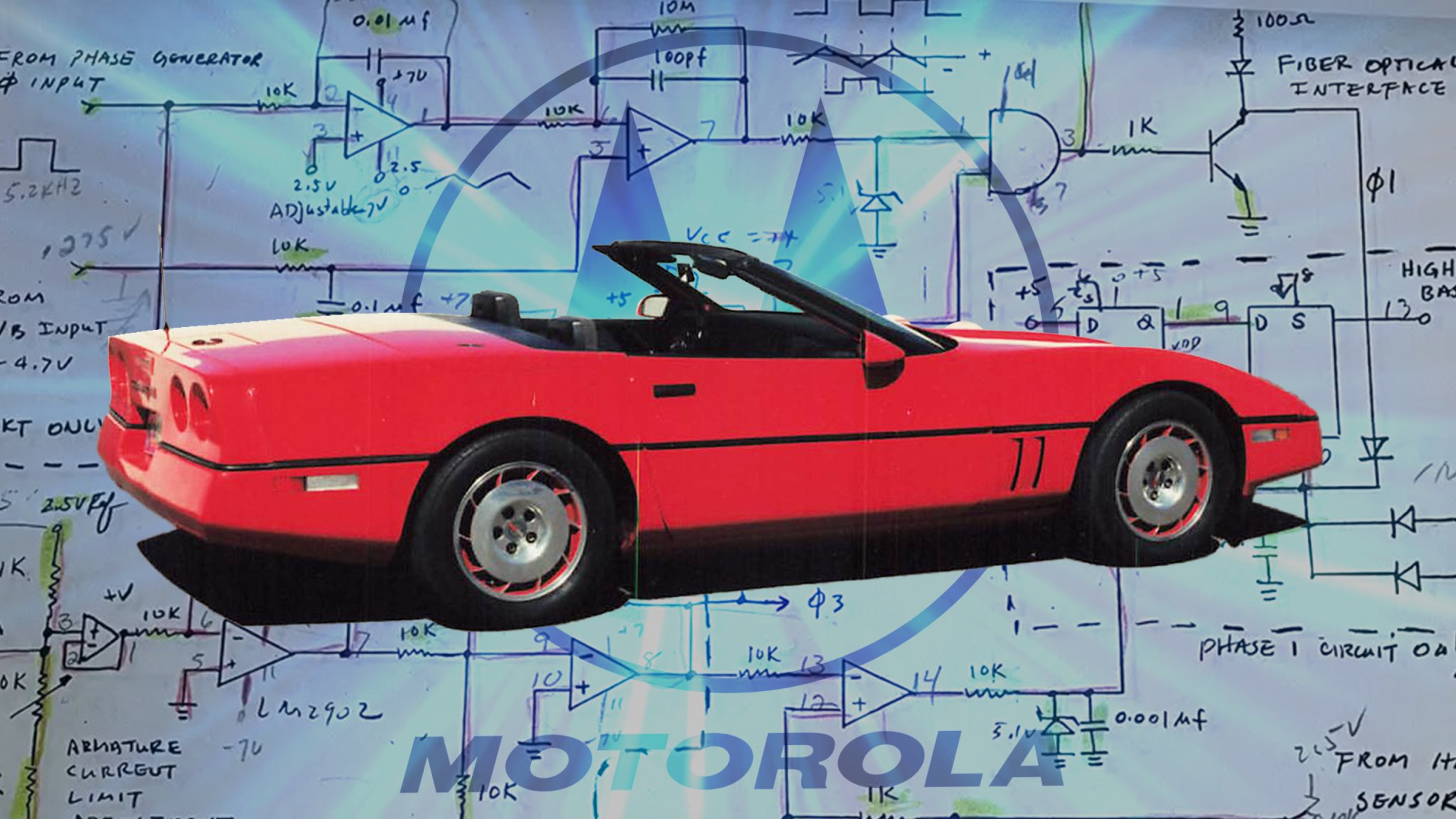

Previously, Ghaem and Gerbetz thought a hybrid muscle car sounded cool. But real decisions had to be made now that a budget was in hand, and the muscle car concept was cast aside for a full-electric C4 Chevrolet Corvette. It was Ghaem’s idea. “I had a ‘63 Corvette that I had for years and years, and I thought a nice Corvette convertible would be great,” he said.

As with the EX-11, Ken Gerbetz made it happen. He got back with Tom Brawner, who found a non-running red 1987 Chevrolet Corvette convertible, perfect for Motorola’s project. The engine was removed and the car was prepped for conversion by Don Karner, Brawner and his crew in Arizona. Back in the Chicagoland area, Ghaem’s team, led by Bob Gerbetz on the ground, got to work designing and engineering all the bespoke motors, controllers, and necessary EV equipment.

By necessity, the Corvette would share a lot of its design with the electric race car project that Motorola executives had also greenlit, now called the EX-12. The Corvette would act as a test bed for Motorola motor, motor controller, and battery tech, as the two vehicles were developing somewhat simultaneously.

This time, the EX-12 would still use a Lola Indy chassis but this time covered in unique closed-wheel bodywork, once again designed by Don Karner and Tom Brawner. According to an Autoweek report from the late, great Tim Considine, everything behind the rear bulkhead of the EX-12 was new. The Lola chassis now had a custom subframe and two new bulkheads to make up for the lack of engine and transmission and maintain rigidity.

Meanwhile, the Corvette’s conversion was meant to be as seamless and stealthy as possible. And because it was meant to serve as a test bed, the batteries needed to be accessible. According to Ghaem, the rear fascia of the Corvette can slide out, taillights and all, revealing part of the Corvette’s batteries for easy swapping, not dissimilar to the EX-11 and EX-12 race cars. The rest of the batteries are sandwiched between the front fender and frame rails, easily removed when the Corvette’s clamshell hood was open.

The powertrain on both cars was designed mostly by Bob Gerbetz. “We made three copies of everything, three motors, three sets of controllers. One set went to the EX-12 racing program, one set for a Chevy S-10 used for battery research, and the third set went into the Corvette,” he told me. Gerbetz’s job was complicated, designing and writing algorithms to make all the motor controller stuff work.

“Ed Li designed the power electronics and did most of the analog design, and Chris Pratt designed the microprocessor board and did the programming,” he added. The five were further aided by a few others: the Gerbetz brothers’ dad, who helped build the motors; lab tech Edison Ramirez, who Bob Gerbetz called “outstanding”; engineer Fred Ostrem, who designed the boxes to house all the electronic components under the hood; and early EV guru Shunjiro Ohba, who lent his shop space to the team for motor and component testing. And that was it.

Bob Gerbetz’s motor was strong, improving greatly from the borrowed and refreshed GE motor from the EX-11. Cumulatively, the EX-12 and Corvette had a combined system voltage of 336 volts, which fed an 800 amp motor controller. The motor would spin to 10,000 rpm and deliver 157 horsepower continuously, peaking at 272 horsepower when hooked up to lead-acid batteries provided by Exide.

The team didn’t really like Exide’s batteries; the output wasn’t that impressive, and they were holding the vehicle back. So someone sourced a set of Nickel-cadmium (Ni-Cad) batteries that were originally meant to start aircraft, which pushed the motor’s total output to over 400 horsepower, Gerbetz said. With the Ni-Cad batteries, the EX-12 “took off like a scalded dog,” in the words of test driver Billy Roe.

But because Exide was a sponsor of the EX-12 program, they were obliged to use the less competitive lead acid batteries. Still, even with the lower-output packs, the EX-12 was fast, able to reach 160 mph. It was such a rocket that even in its less-than-ideal state, its mere existence was once again a threat to GM.

According to Bob Gerbetz, Don Karner had been invited to showcase the EX-12 on an exhibition lap during the 1994 CART Grand Prix of Cleveland. “Don Karner and Tom Brawner showed up in Cleveland with the EX-12, but GM was doing a demo with a fleet of their Impact EVs and told the promoter of that event that they didn’t want the EX-12 doing a demo because it’s a very fast car,” he claimed. “So the promoter asked GM for $50,000 to keep the EX-12 from driving around the course and they agreed. So, the EX-12 was no longer part of the show.” I haven’t been able to verify this, but it definitely sounds plausible given the pre-existing tensions with GM over the prior EX-11 versus Impact concept showdown.

The Corvette Is a Smashing Success. And Yet…

At the same time, the Corvette was coming together in a few short months, swappable batteries and all. Bob Gerbetz initially wanted the Corvette to use a unique AC synchronous motor, but due to time and budget constraints, the Corvette would use the same DC motor used in the EX-12, mounted in the engine bay ahead of the stock “Doug Nash 4+3” manual transmission. “The motor can actually be modified and converted to an AC synchronous motor with a bit of redesign and fabrication of some new hardware,” he said.

In all, the Corvette gained about 700 pounds in its conversion to electric, bringing the total curb weight to 3,800 pounds. Like the competition version of the EX-12, the Corvette ran the inferior lead-acid batteries from Exide. The result may have been heavy, but the instant torque from the electric motor meant that it matched or bettered the performance of the malaise-era 240-horsepower V8 engine. The team had ordered a second set of aircraft-grade Ni-Cad batteries, meaning the Corvette would no doubt be capable of the claimed 400+ horsepower. Unfortunately, those wouldn’t show up until it was too late.

Still, it was a dream to drive. Range was maybe about 50 miles max with those lead-acid batteries—not much by today’s standards, but still a great starting point 30 years ago for something built in a few months. “It was a really nice car, really nice, smooth acceleration. You didn’t have to shift gears or anything, it had enough power that you could start in any gear and it would spin the wheels,” Ghaem recalled.

To the team, the project was a smashing success. The car drove great, charged well (if slowly), and the swappable batteries made it a practical design. They’d learned so much and felt empowered to do even more research; EV motor controllers appeared to be the way forward, and the group seemed to have Motorola’s blessing. Everyone felt like they were working on cutting-edge technology that could define the future of cars. “Basically, it was five guys with a vision. We had a blast,” Ken Gerbetz said.

As they completed the Corvette, the group eventually resurrected the old hybrid muscle car idea, starting the initial planning stages of what would be an even bigger technological showcase: a 500-horsepower hybrid system in the body of a Ford Mustang.

“The hybrid Mustang was to be a current model year (1994 or 1995) conversion starting with a glider, basically a car with no powertrain. We were working on a 500-horsepower motor and controller and engine controller for a small 50-hp range engine with a combination of Ni-Cad and thin metal film lead-acid batteries for the battery pack,” Bob Gerbetz said. “The thin film batteries were good for peak power and the Ni-Cads good for storing energy and decent for power. We built the brains of the AC controller and were going to do some lab testing at 40 hp on a smaller motor and work on the overall vehicle controls.”

Unfortunately, that hybrid Mustang never made it off the drawing board. Despite how far they’d come, everything was about to fall apart.

Got a tip about another long-lost prototype? Get in touch here: tips@thedrive.com