Over the weekend, Roborace revealed its newest autonomous electric race car at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona—and it’s a carbon fiber, hourglass-shaped futurist’s wet dream.

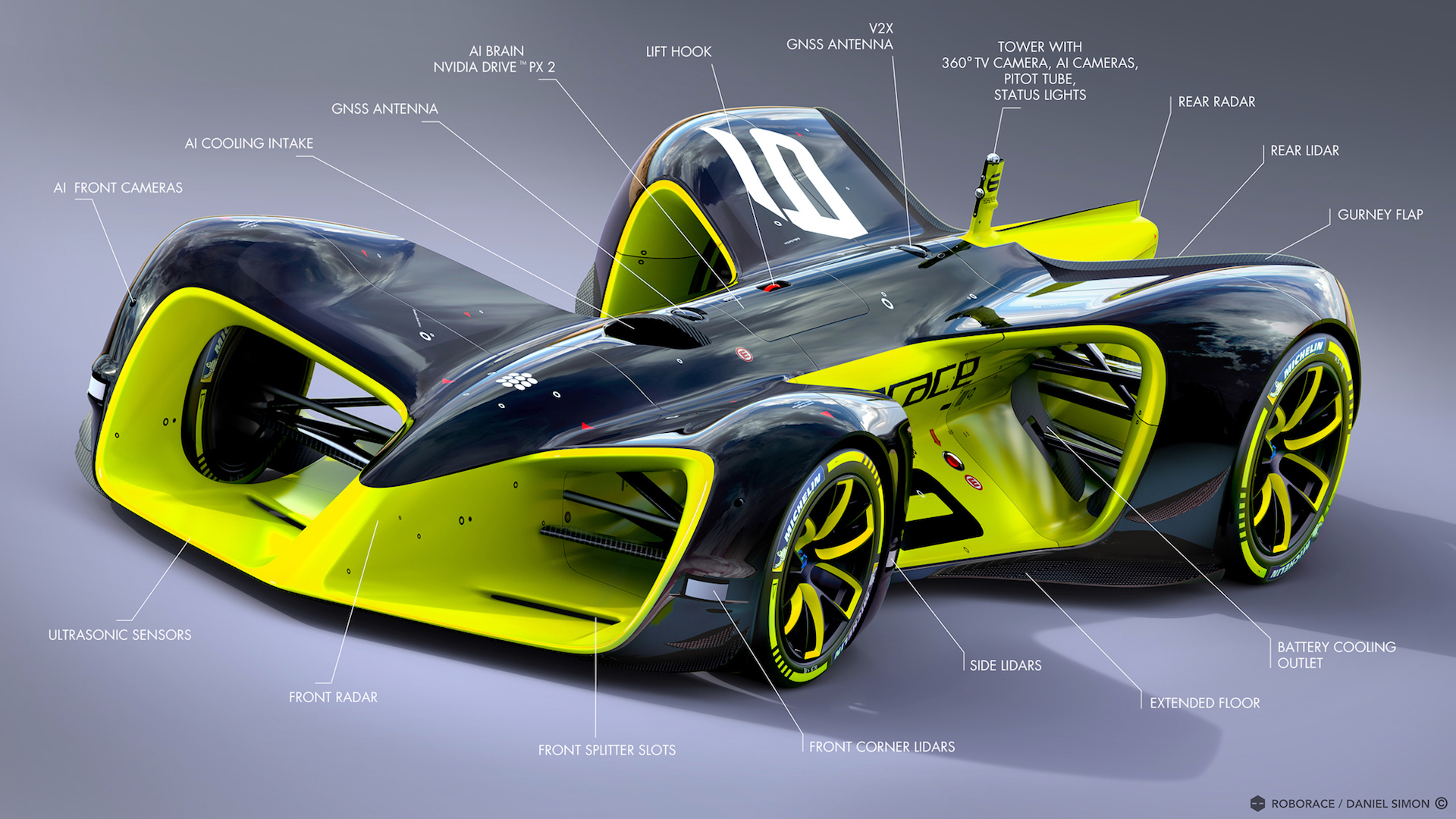

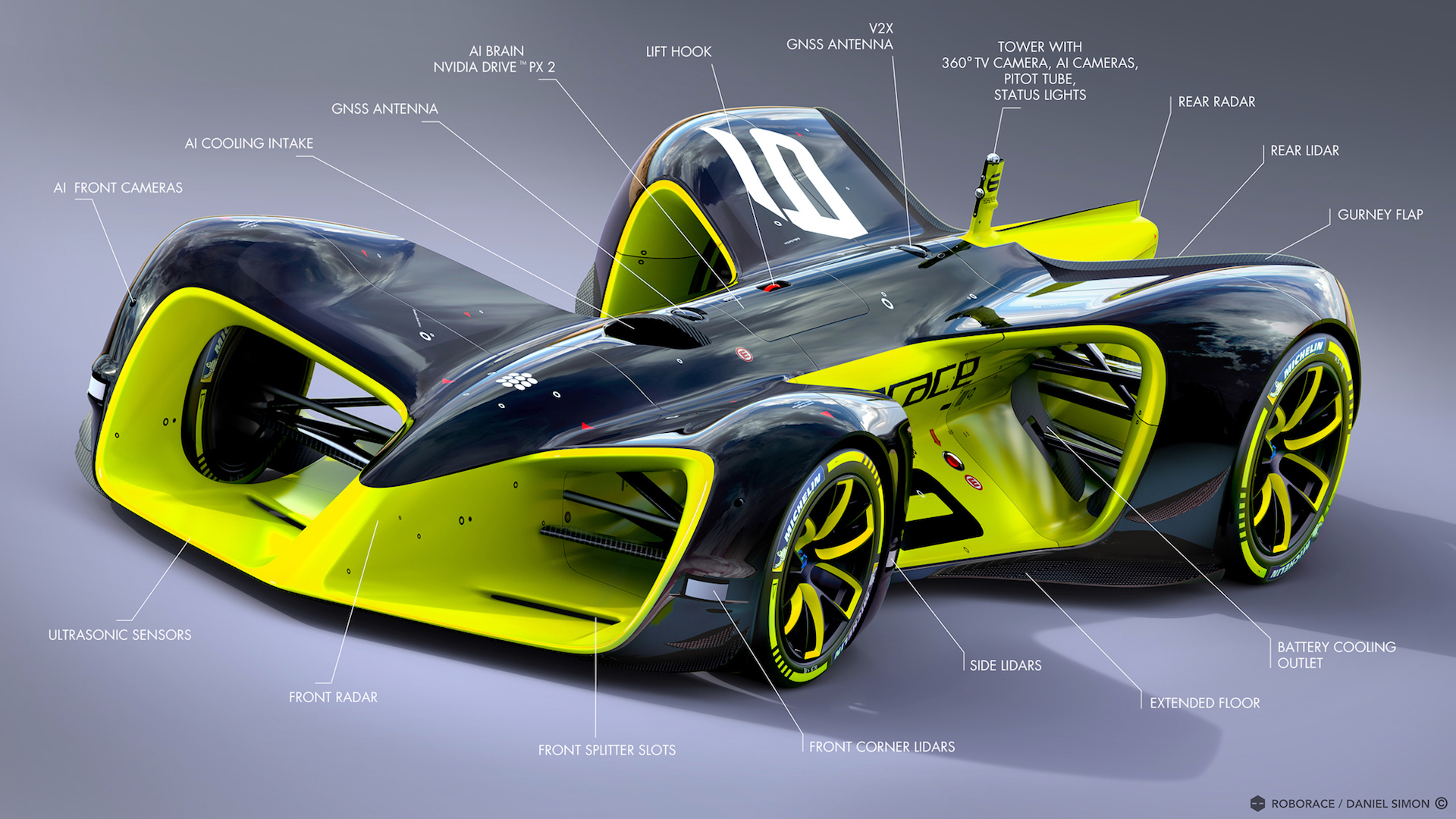

Designed by Daniel Simon, who has created cars for Hollywood sci-fi films such as Tron: Legacy, Oblivion, and Captain America, Robocar weighs just over one ton (2,151 pounds) and can hit nearly 200 mph from its 540kW (740 hp) battery pack and four 300kW motors. Helping guide the futuristic missile at breakneck speeds are five LiDar arrays, 18 ultrasonic sensors, six cameras, two optical speed sensors, GNSS positioning antennae, and an NVIDIA Drive PX2 processor, which can apparently handle more than 24 trillion computations per second.

Roborace, the driverless racing series in which Robocar will compete, will require that every team uses their own Robocar—identical, hardware-wise, to every other team’s. Teams will then be expected to develop their own “standalone software” upon which the Robocar’s hardware will rely.

The biggest hurdle Roborace will encounter, I think, is whether the races will not only be able to draw in an audience, but also whether that audience will be sustainable. And while it will ultimately be people—engineers and scientists—programming the AI software for each team’s racer, the lack of an overarching human element could be the Achilles heel of Roborace.

Racing is entertaining is because viewers watch fellow humans break barriers, set records, and put their necks on the line in the face of potentially serious injury and death. Racing is ultimately a human story; a sociological phenomenon that celebrates humanism. We hang up posters of racing icons like James Hunt, Stefan Bellof, and Jim Clark because they put their very human lives at risk when they got behind the wheel. They were personally inspiring. I can’t imagine we’ll hang up posters of Roborace software engineers who program the cars instead of pilot them, even if they are the biggest human element of Roborace. (Posters of the actual Robocar are a different story, though, because they are pure, futuristic robotic sexiness.)

Simon, Robocar’s designer, doesn’t seem to think this way. “It was very important for us to create an emotional connection with the unmanned cars and bring humans and robots together to define our future,” he said to Motorsport.com. I’m curious how he proposes going about that, though, precisely because that’s the lynchpin on which the success of Roborace rests—an emotional connection, which, by nature, is exclusively limited to sentient beings, not AI.

On the bright side, Roborace will be an impressive testbed for technological advancements in autonomous systems. If 200 mile-per-hour self-driving cars can scoot around a race track without hitting obstacles, or each other, while laying down impressive lap times, then there’s no reason that technology shouldn’t trickle down to consumer cars. But as far as an enthralling racing series goes, I can see the novelty wearing off after an audience watches a single race, or even a single lap. I wouldn’t mind being wrong, though.