In 2014, Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo blew apart on re-entry. It was a major setback to Sir Richard Branson’s broadly publicized effort to “democratize” space travel—albeit, for the one percent, as tickets for the buying public run $250,000. Still, Virgin Galactic, unlike Elon Musk’s SpaceX, stands apart. The latter is largely about providing NASA and other space agencies cheap, reusable rockets; Branson’s purpose with Galactic remains consistent with his roots. This is a man who sells pleasure, in the form of everything from cola to hotels, and he wants a zinger of a space plane, with viral video from delighted first-comers doing more for marketing than the entirety of Virgin Holdings’ annual ad budget.

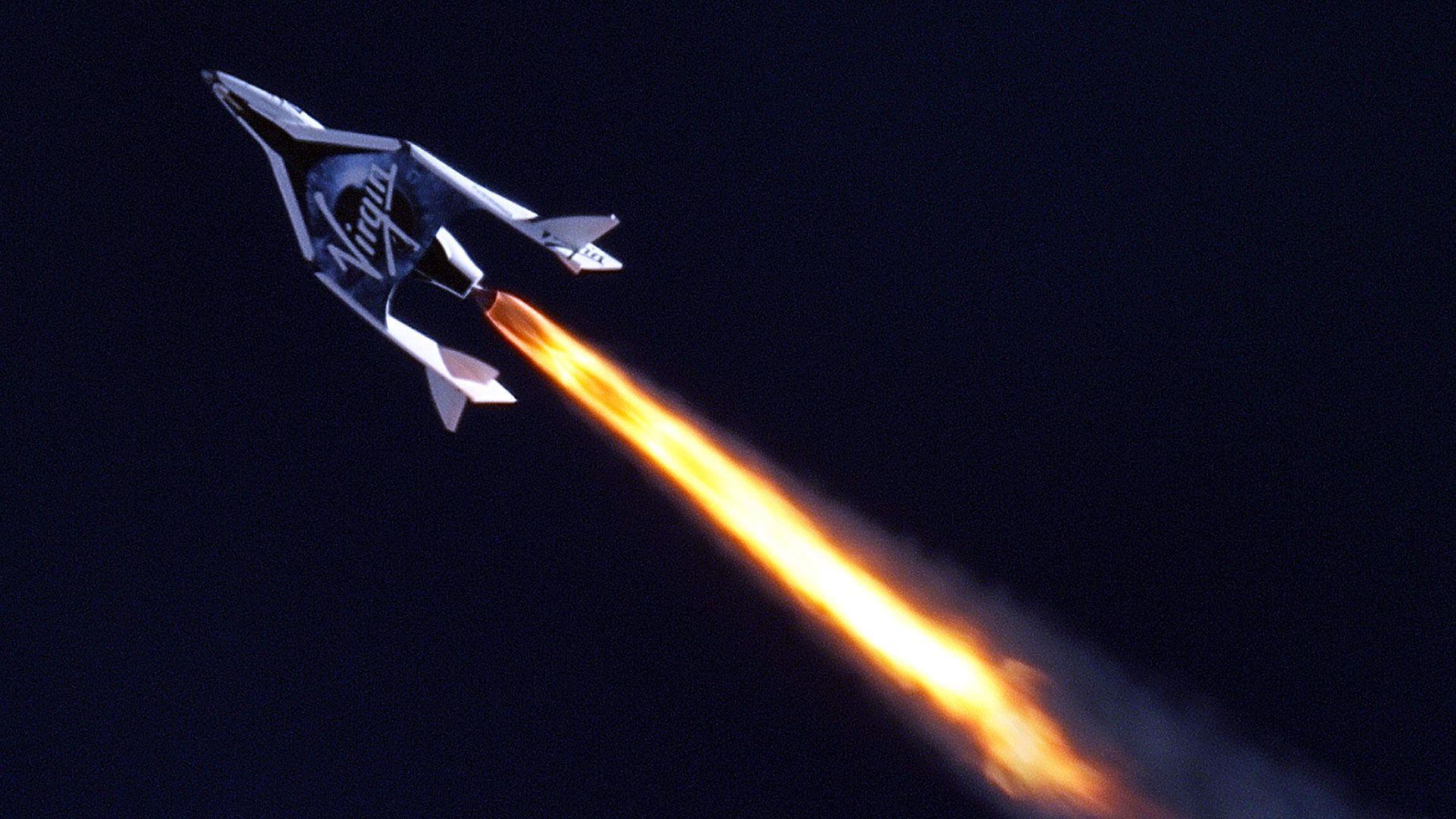

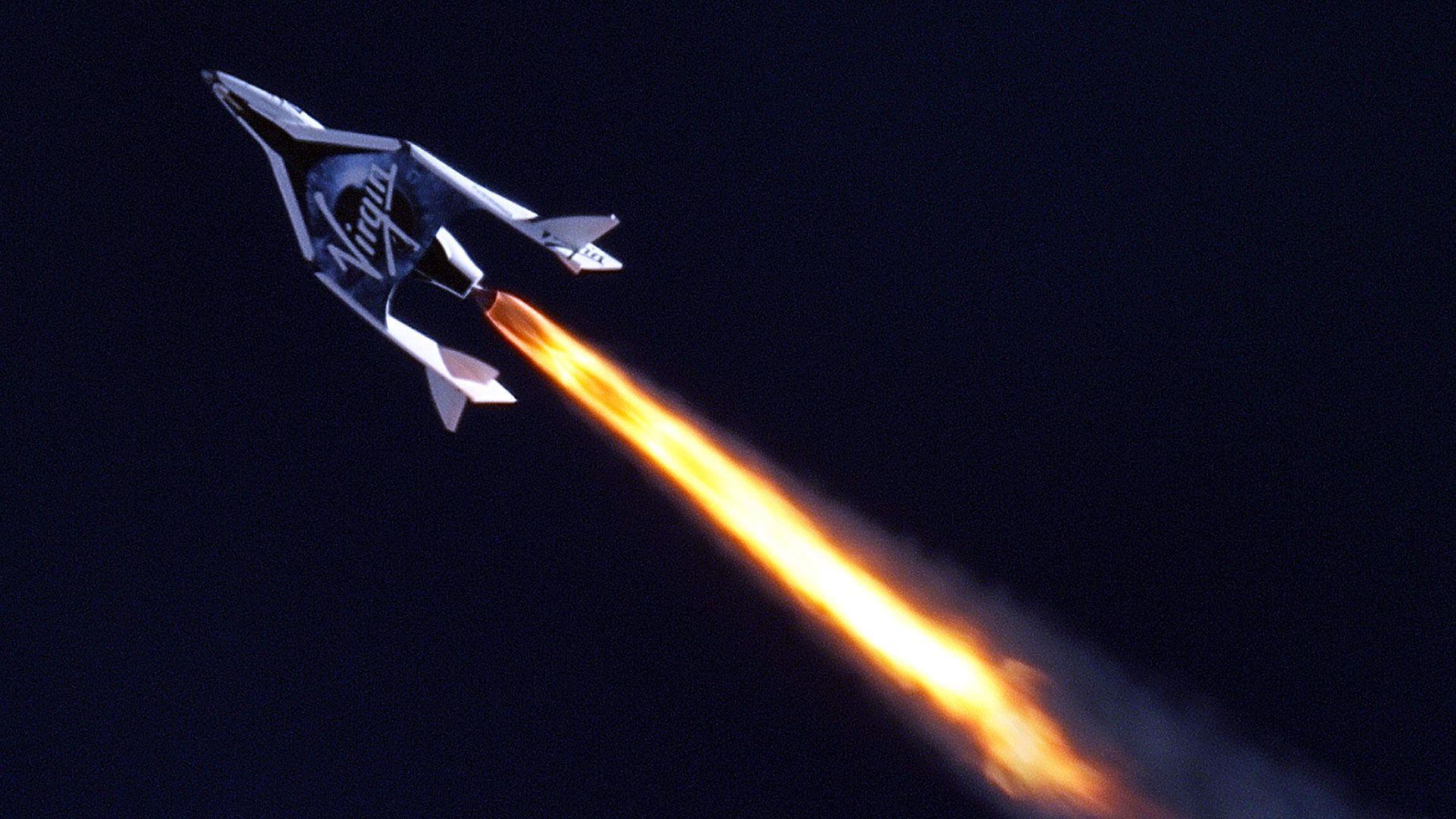

Now about that crash. In the Virgin Galactic effort, a small craft is carried skyward by a larger one, then the smaller space plane fires a rocket to achieve sub-orbit altitude.

During the 2014 test, the NTSB report found that co-pilot Michael Alsbury, who died during the break-up of the space plane, had improperly deployed the tail wings during descent. The rear wings are meant to angle upward to slow the descent, but, because Alsbury unlocked the wing system at too slow a fall rate, the aerodynamic load was off, over-powering the wings’ motors and forcing them into a 60-degree angle that, according to the NTSB report, caused “catastrophic structural failure.”

The new craft is nearly identical to SpacePlaneTwo, but now it’s impossible for a pilot to mis-time the rear wing deployment. Virgin says the protocol for testing WhiteKnightTwo will be exceptionally rigorous, and that the company is not in a “race” with rivals in the private space realm.

“Very seldom can you go through two accidents where somebody dies. They need to get it right,” warns Marco Cáceres, Senior Space Analyst and Director of Space Studies with the Teal Group, a Washington, DC-based aerospace consultant firm. To get it right, says Cáceres, it’s key that Virgin Galactic has some minor mishaps: “So you can see them, address, them, fix them.”

Then, he adds, this new ship must get beyond glided flight.

“They’ve had a number of glided flights. Now they really need to have a dozen or more powered flights and go to the edge of space, then put civilians up there.”

Cáceres says that people are still going to die probing space, and for decades to come.

“Engines are engines. They vibrate, there are fuel leaks. In mature industries—from railroads to air travel to the automobile—thousands of people have died and still die. People accept that when industries are relatively mature. But there are not that many flights of rockets and spaceships, so we’re not there yet where we’re as accepting.”

And he notes that Branson, unlike SpaceX, isn’t launching cargo or satellites. If those rockets blow up, the business goes on. That certainly won’t be the case if Virgin’s eventual passengers perish.