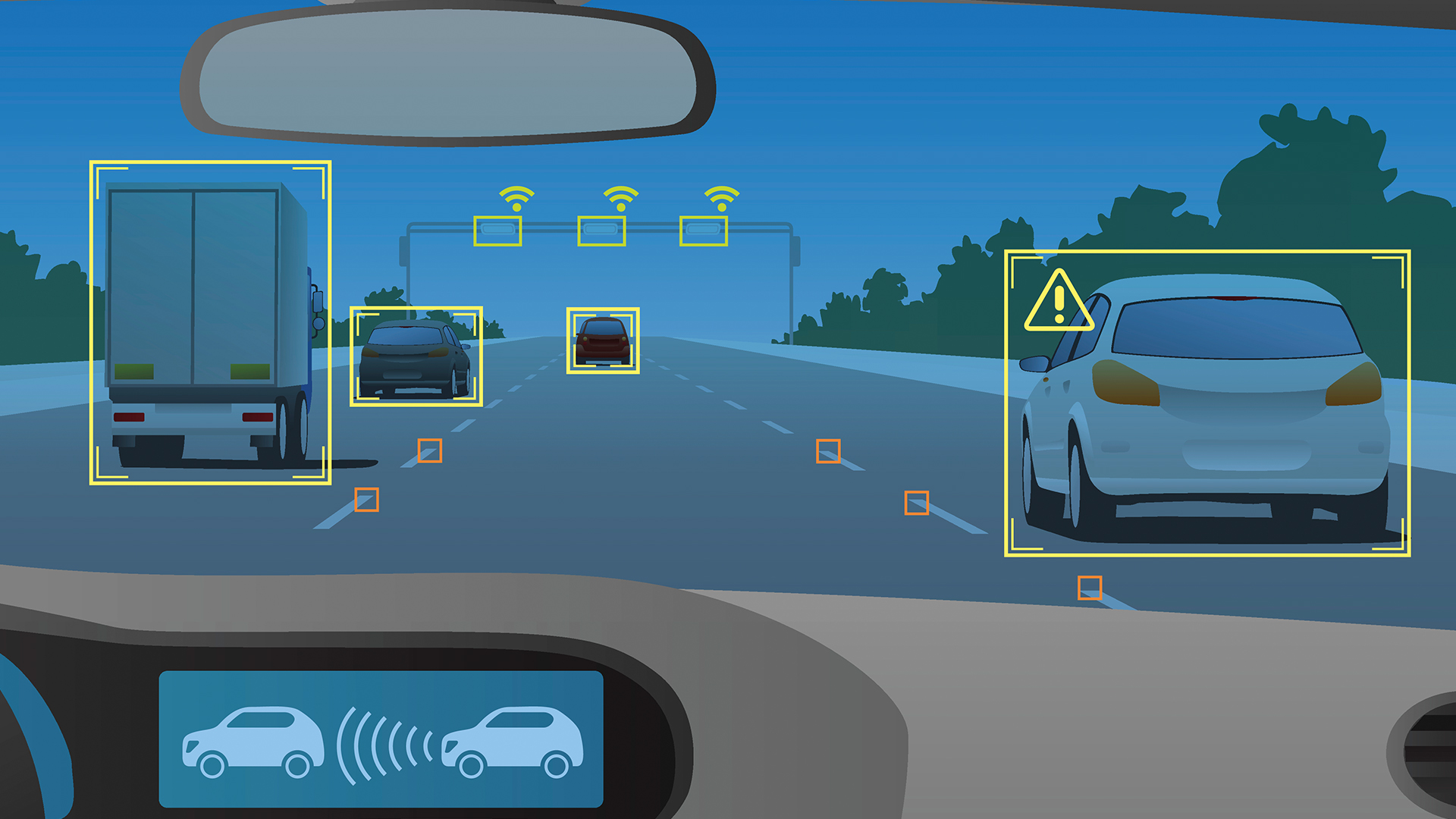

Vehicles on the road are becoming connected at an alarming rate, and the governments of the world are enabling its progression. While the intentions of interconnected vehicles are good, such as traffic data sharing and the ability to provide insight to active road conditions miles away from a driver, and as pointed out by Forbes, this also enables vehicle manufacturers to collect large amounts of data on the driver and his or her habits behind the wheel. But just what happens with that information once it’s collected?

A lot of people are willing to just give away personal data without blinking. Whether it be by navigating their way across town with Waze (which has historically shared non-identifiable data with local governments), or by simply using Facebook. As popular as it is, the latter social network, uses information that you and your friends provide (as well as information supplied by third party advertising partners), to curate ads and other targeted features towards you. Not only could a connected vehicle collect data regarding your location and driving habits, but automakers could easily provide these data to third-party agencies who use this information for advertising and statistical analysis purposes, or even to insurance companies which could go as far as using the information to determine how high your policy rates should be.

Other possible scenarios are simply for the auto manufacturer to use its own data to up-sell products and services to owners. Utilizing information from a modern car’s complex Controller Area Network (CAN Bus) system, it becomes possible to record active data from the vehicle’s sensors, producing statistics regarding oil level, how hard an owner brakes or accelerates, tire pressure, fuel consumption, malfunction indicator lamp codes, and more. All of these data could be put to use in order to preemptively sell drivers services based on their driving habits, rather than a dealer sending a postcard in the mail to remind you about your car’s upcoming 60,000-mile service.

The consumer may also be offered in-car services that they could potentially purchase at the touch of a screen, much like another form of advertising in the vehicle. Though these data never technically need to leave the manufacturer, it can easily result in dealers offering what they see as value-added services that consumers may otherwise not buy into.

Big data is a market all its own. Researchers and McKinsey & Co. predict that vehicle data monetization could become a $750 billion global market by 2030. Some companies who claim to not sell data still share data willingly using bartering and other tactics which don’t technically monetize the information but still release it from the hands of the manufacturer. BMW, for example, has a marketplace called CarData, which it operates in Europe in collaboration with IBM. The service takes telemetry readings from cars which have not opted out of collection and aligns it for use in BMW’s marketplace.

Another example of car data collection involves everyone’s favorite connected electric car manufacturer: Tesla. The automaker recently began collecting video footage from user vehicles earlier this year to improve its Autopilot functionality. It claims that the video is anonymous and that no footage can be linked back to a single vehicle’s vehicle identification number, making it searching by car impossible in Tesla’s system. All in all, it seems like a quick way to be able to access data to improve services and products. Fortunately for the company, it already has hundreds of thousands of vehicles on the road worldwide, collecting data to send back to the company’s information powerhouse in the cloud.

We asked Tesla about its privacy policy and were referred to the information on its website. Under Tesla’s privacy policy, it claims that information collected can be shared with business partners, service providers and “other third parties when required by law, and in other circumstances.” This may seem harmless, however, some ethical concerns have been raised when the manufacturer historically provided detailed information regarding car crashes to sources like The Guardian.

We’ve had talks of how regulation is both an important and extremely necessary part in the autonomous vehicle world, however, one disturbing trend that seems to be lacking is the disregard for a more blanket approach to consumer data privacy in previously proposed legislation and industry guidance. Big data farmers have practically unfettered access to consumer data, and manufacturers seemingly have very thin limits on what constitutes unethical data sharing. A person’s means of transportation, a previously unconnected area of the human life, is now being added to the intertwined world of personally-identifiable information, further marketing that person as a product to companies.

We reached out to some of the larger companies that are developing autonomous cars to see just how driver data privacy is handled, however the companies that did respond to us, responded with links to pre-established privacy policies posted online, with the exception of Volvo, whose spokesperson told The Drive that “all data is owned by the customer.”

As manufacturers begin to develop their own ride-sharing alternatives to traditional driving, big data becomes even more prevalent than ever. The utopian society of trafficless self-driving cars that require zero interaction from drivers may be little more than a shill for advertising and data collection to users, and drivers that still own their vehicles will seemingly find the mechanics of their daily commute to become a “freemium” experience.