Let me ask you a question: Have you ever heard of a W10 engine? Not a V10 or a W12—a W10. Supposedly, Volkswagen made a few prototypes, but that was decades ago. Now, an experimental W10 has emerged out of nowhere, and its owner wants to know more about its history, as well as how to bring it to life. But they’ve hit a brick wall, and their only hope is that someone out there has the knowledge they seek.

I’ve pored the internet and reached out to VW for all possible information on this mysterious W10, and I think I have a working idea of why the engine exists and what might be needed to make it run. But let’s not put the cart before the horse.

Telling the W10’s story requires flipping the calendar all the way back to 1991, to the birth of VW’s VR6 engine.

In a nutshell, the VR6 is a six-cylinder engine that’s shorter than an inline-six, but narrower than a conventional V6. That’s because it’s just a V6 that’s been squeezed down to a 15-degree cylinder bank, which also allows it to use just one cylinder head. This lets more cylinders and displacement fit a smaller engine bay, making a VR6 more suitable for smaller cars than a V6 would fit—or enhancing packaging for a high-performance car.

VW later expanded on the idea with the W engine, which joined two VR engines at the crank to make W8, W12, and even Bugatti’s famous W16 engines. The W10, however, began by stepping in the opposite direction; by downsizing.

From the VR6, VW developed a smaller 2.3-liter VR5, which it made from 1997 to 2006. These five-cylinders had iron blocks and aluminum heads, initially with two valves per cylinder, but later upgraded to four with variable valve timing. They made 168 horsepower and 162 pound-feet of torque in the Golf, New Beetle, Passat, and Bora, but in only some markets, and only for a decade. The reasons seem obvious: It wasn’t very powerful for its displacement, but it was complex, and therefore harder to work on. (It was the second shortest-lived configuration of all the VR and W engine family, second only to the W8 which lasted three years.)

Before VW canned the VR5, it conceived a W engine it could derive from it—a W10. Some information on the W10 concept survives in a VW service training document from August 2001, Self-Study Programme 248: The W Engine Concept. It describes “a W10 engine consisting of two VR5 engines” as “a possibility.”

SSP_248The document goes on to outline the advantages specific to a 72-degree W10, observing it needs no crankpin offset for an evenly timed firing sequence. VW also saw fit to include these passages in a U.S. republication of the document in February 2002. Why VW thought technicians needed to understand this may have been related to a variant of the Phaeton luxury sedan rumored to have been in development at the time.

Though the original story has been lost, an archived May 2003 forum post on VW Vortex quotes The Detroit News as reporting on a potential long-wheelbase Phaeton. Supposedly, one powertrain option was to be a W10, alongside a V12 (though the Phaeton went on to use a W12 instead). These were to be matched only with automatic transmissions, and power both extended-wheelbase and full-on stretch limousine models.

Obviously, no W10 Phaetons were ever offered, and the Phaeton has been dead for years—the W12 recently joined it. But VW appears to have laid the groundwork for a W10 Phaeton because one of its experimental engines (or at least, most of one) survives today.

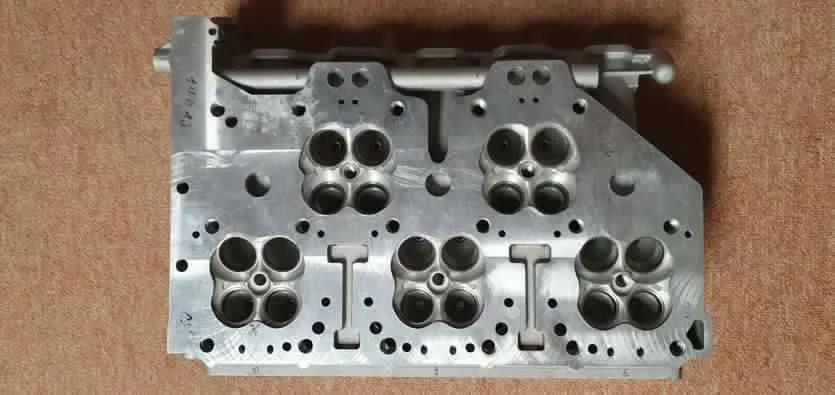

The only known VW W10 engine in existence is in the hands of a German VW mechanic, who recently shared photos of the disassembled motor on Instagram. Ari, as he goes by, told me he acquired the engine in 2011 from a customer who claimed they had prevented it from being “shredded” in Wolfsburg (where VW is headquartered). From what Ari heard, his engine was one of three, with the other two presumably being destroyed. Unfortunately, though, that’s as deep as his—or pretty much anyone’s—knowledge of the W10 goes.

“It’s nearly impossible to find anything about the W10 on the [world wide web],” Ari told me. “[The] sad thing about it is there are no spare parts for it,” he added, stating that he “would like to get it somehow [sic] running.”

At this point, Ari and the sources above seem to offer a more complete version of the W10’s history than VW itself knows. According to a VW spokesperson I asked for historical information on the W10, the institutional knowledge of W engines has been lost. Many of the people who remember those programs are gone now, as you’d figure with even Bugatti’s W16 on its way out as VW careens into EVs.

But still, there may be hope for bringing this unique W10 prototype back to life. VW’s description of a W10 as two VR5s combined could hint at engineering shortcuts VW may have taken to build the prototype—therefore, it may share some components. Those can’t include more than one cylinder head, as the cooling passages visibly differ on both banks, but the W10 may have used rods, pistons, and camshafts of similar spec to the VR5. Its front end might be reconstructed using a combination of VR5 and W8 or W12 parts too. The block is totally unique, though: it’s aluminum, not cast iron like the VR5s.

It’d be better not to rely on guesswork though, so we’re casting this net out for Ari in the hopes that the W10 can fire up once again. If you know anything about this W10 engine, anything at all, email me at james@thedrive.com. VW may have given up on the W10, but that doesn’t mean the rest of us have to.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: james@thedrive.com