The name DeLorean is known in all corners of the world. The former GM executive turned automobile entrepreneur made waves when he launched the gull-winged stainless steel sports car known as the DMC-12 in the early 1980s. His time in the limelight was cut short after he was arrested and instead of being known for his contributions to the auto industry, John Z. DeLorean became known as the man who was charged (though acquitted) with a conspiracy to smuggle cocaine, and the DMC-12 mainly as the time machine in 1985’s Back to the Future.

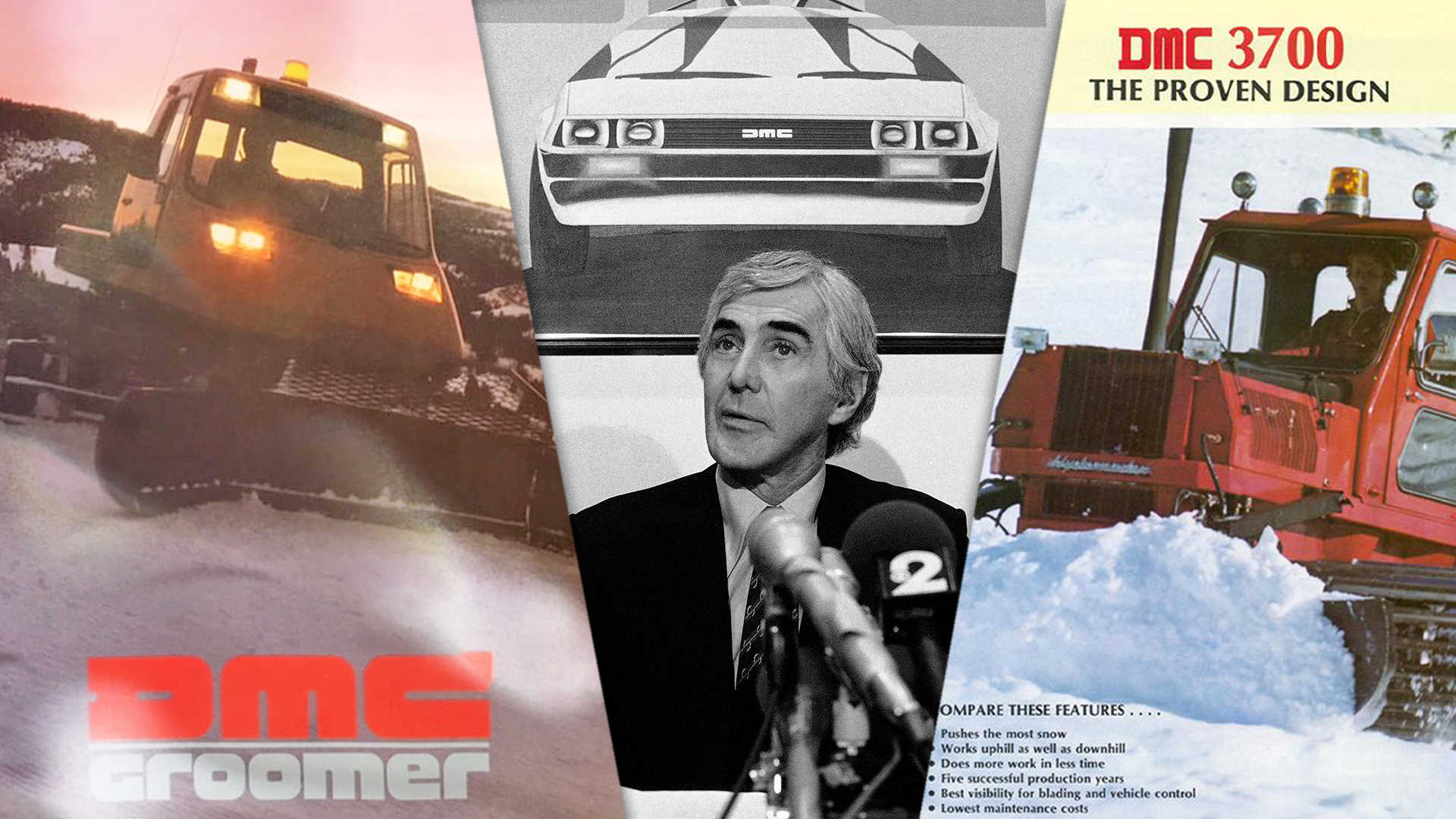

Even before the famous scandal, there was another kind of snow he was interested in: the stuff falling from the sky. His passion for winter weather and vehicles that could traverse those icy conditions became one of DeLorean’s main sources of post-GM income (and a significant pawn in the post-conviction DMC bankruptcy) but was somehow simultaneously his least known business endeavor. In fact, the first DeLorean wasn’t the DMC-12—it was a snowcat.

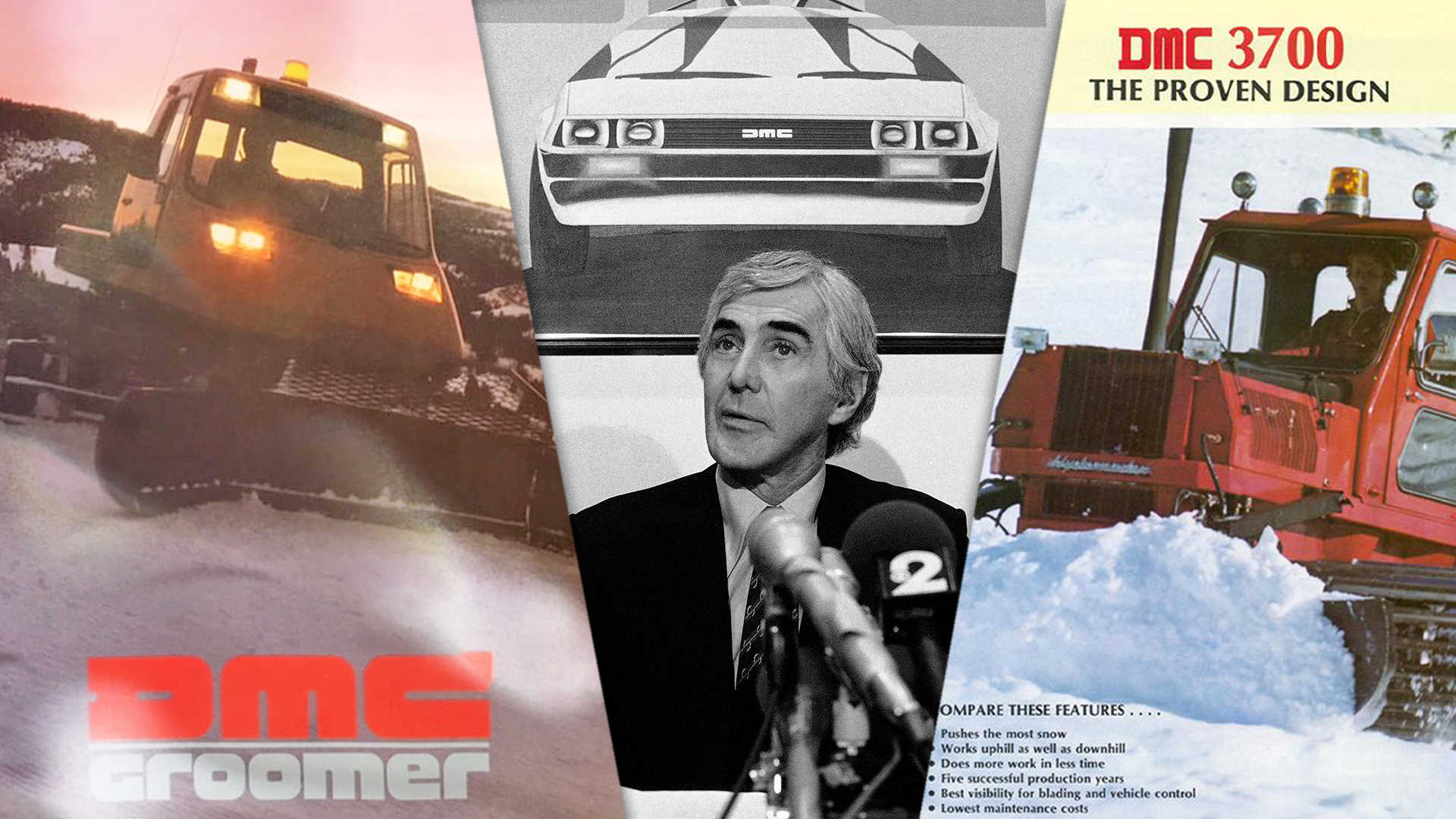

The DeLorean Manufacturing Company, as it was branded—and not to be confused with the DeLorean Motor Company—was a turnkey purchase for the serial entrepreneur in 1978, just as his automotive ambitions were gathering real steam. The business had been building snow groomers for several decades as part of a larger multinational conglomerate Thiokol. Somewhat amazingly, it represented more than half of the U.S. market share for snow grooming equipment at the time.

And so, DeLorean’s snowcat business was a success at first. But like his car company, the Utah-based DeLorean Manufacturing Company would become entangled with the man’s legal battles until it was forced to rebrand before changing hands and dwindling into nothingness. But for a brief moment in time, John DeLorean’s name didn’t just mean building a car—it also meant snow groomers, aircraft tugs, skid loaders, treadmill frames, and more.

DeLorean Loved to Ski, Apparently

DeLorean’s snow-machine era began with a chemical-aerospace company called Thiokol. It’s since restructured several times and finally merged with Northrop Grumman, meaning it’s not as relevant today. But in the 1970s, Thiokol was making everything from rocket boosters for NASA’s space shuttle (a project which later resulted in the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster) to lift and grooming equipment for ski resorts. Perhaps thinking it should focus more on its core competencies—spaceflight is tricky—Thiokol started downsizing or shedding some of its ancillary concerns that decade. This included its cold weather operations; a corporation founded by two former employees acquired the ski lift portion of Thiokol, while the snowcat and groomer manufacturing business was purchased by a flashy guy who had made a name for himself at General Motors as the designer of the Pontiac GTO and Firebird: John Z. DeLorean.

It was 1978 when DeLorean approached Thiokol saying he wanted to buy its snow equipment manufacturing division, located in Logan, Utah. Nobody knows exactly why John DeLorean had his eye on Thiokol, but his son Zach told me that John loved to ski. He theorized that his father’s passion for the slopes and keen eye for potential investments may have made a turn-key operation like building snow grooming vehicles seem like a rather smart investment, especially for the man who spent nearly two decades working in a high-level position for GM. Regardless of the reason, DeLorean was set on buying.

The former GM exec ponied up $8.5 million for the deal, a sum which he claimed to have been loaned by Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus and man responsible for some of the most important engineering decisions related to the DMC-12’s chassis and suspension layout.

This transaction would later become a topic of interest to federal prosecutors in 1986 during one of DeLorean’s legal battles, as the government learned that the money was funneled through a Swiss-owned Panamanian company called General Products Development Service (GPD), the same company which made the design arrangements between DeLorean Motor Company and Lotus. Whether or not Chapman authorized the loan is something still up for debate today—DeLorean produced documents at the time verifying the loan, while DeLorean’s ex-wife Cristina Ferrare claimed that he not only had the means to forge documents, but also practiced forging the signatures of his business partners. Either way, Chapman took that secret with him to the grave in 1982 when he died of an apparent heart attack.

The First DMC Didn’t Need Roads

Back in 1978, the Thiokol purchase was finalized and the DeLorean Manufacturing Company sprang to life. Soon, the snow groomers that were manufactured at the Logan facility began to bear DeLorean’s name. The metal plate which bore the vehicle’s serial number, weight, and manufacturing details was now stamped with “DMC“, and the words “DeLorean Manufacturing Company” were proudly displayed across the left side of the vehicle’s dashboard. That’s right, a full three years before the first DMC-12 production car rolled off the line in Ireland, the very first vehicle bearing the DeLorean name was actually a snowcat.

It’s important to note again that the DMC that built the snowcats was DeLorean Manufacturing Company and not DeLorean Motor Company, the latter being responsible for the DMC-12 car. Apart from having the same owner, the two companies were independent of one another. We’ll refer to the snowcat maker as DMC-Logan from here on out to avoid any confusion.

These DeLorean-branded snowcats still pop up for sale today, and they’re not cheap either. In good condition, the 40-year-old snow groomers can still run upwards of $40,000 and have quite a niche community following.

Believe it or not, though, this isn’t the most obscure thing that DeLorean cooked up with this side hustle. At the same time the DeLorean Motor Company was building the DMC-12, the DeLorean Manufacturing Company was building an even lesser known product that was also really good at moving weight: aircraft tugs.

Coined the DMC T-40, these vehicles are shrouded in mystery. In fact, their very existence often surprises even the most veteran DMC-12 owners, as no other four-wheeled DeLorean was ever known to have made it to production. The story of how DeLorean decided to make airplane tugs has trickled out in bits and pieces as a few models have changed hands and made it into private ownership over the last forty years, but details remain sparse and hard to confirm. On the rare occasion that an auction house or military surplus firm happened to list one online, the link is typically posted deep within a DeLorean owner’s forum. One such example for sale recently appeared in a now-deleted Craigslist post for $2,500. Even still, the owner of the tug didn’t really know the history of how these boxy open-top utility vehicles came to be.

That’s where we come in.

DeLorean’s Airport Tugs

In 1980, having run the snowcat business for a couple years and with the launch of the DMC-12 car imminent, DeLorean spotted a rather interesting military contract that would allow the company to expand its product offerings to something other than snow groomers. One of the workers who was there at the time told me that the U.S. Air Force was looking to order 50 aircraft tugs, and somehow DMC-Logan ended up winning the contract. Using the company’s existing supply chains and helped out by a simplistic design brief, DeLorean just started building them.

To learn more about how it went down, I turned to a number of former employees at the Logan plant. Each individual spoke passionately about the work they performed and the people who they worked with—from cab painters, to engineer, managers, and everyone in between. The workers, many of whom had been there for a long time, had become a family, and DeLorean a somewhat distant father to them, occasionally stopping by the plant with his then-wife. Quite a few workers recalled Cristina Ferrare visiting the plant in a “stunning” mink coat, turtleneck, and Levi jeans while the charismatic founder took the time to have friendly chats with each and every one of the plant’s 200 workers that he passed.

“We were really excited to meet John!” former employee Karole Roskelley Sorensen told me, “He brought his beautiful wife and introduced themselves to us in a company meeting. I still remember that day well. She was wearing a black long sleeve turtleneck and Levi’s with her hair pulled back in a simple ponytail, and she looked stunning.”

Fueled with passion for their work and excitement stirred by their new silver-tongued celebrity owner, the team pulled together and got to work building the T-40. For the tug’s power, engineers from DMC-Logan used a Chrysler-sourced engine and transmission. Under the hood was a 3.7-liter slant six which output 80 horsepower to a Chrysler TorqueFlite A-727 3-speed automatic transmission. The transmission sent power to the rear axle via a reducing gear as to maximize torque output. When in full stride, the T-40 could reach somewhere in the neighborhood of 30 MPH—perhaps the slowest DeLorean ever built.

The slow speed was exacerbated by the tug’s surprisingly heavy footprint. The unit tipped the scales at a rather impressive 5,700 pounds, much of which could be attributed to the ballast that the workers filled the tugs with in order to ensure that the units would have traction when towing heavy objects.

David Smart, one of Logan’s engineers who became the company’s Manager of Operational Services, said that using a Chrysler powertrain was out of the norm for the company. In fact, he recalls that the option was only used because it was specified in the contract, as DMC-Logan would equip its snow groomers with Ford industrial engines for gasoline power plants, and its diesels would receive either a Caterpillar or Volvo engine.

After the tugs were built, workers needed to verify that the vehicles could tow up to a rated weight, so DMC-Logan built a test track along the northern edge of its property to test all finished products. One former worker told me that staff was instructed to drive the tugs around when they had any downtime, as the Air Force wouldn’t accept delivery of any unit without a certain amount of hours on the clock. As each unit was finished, it began its trek around the 900-foot inclined track. The tugs would tow a prescribed load up the incline, put on its brakes, and take off from a stop to ensure the heavy load could be moved.

FLIS data shows that DMC-Logan sold each unit for $8,755. Today, that would be the equivalent of around $25,511. Needless to say, the income from the T-40 was pretty good considering it cost around the same as a brand new Toyota Camry—despite being much simpler and using a powertrain developed in the 1960s. It was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to government contracts. DMC-Logan built a number of vehicles for various branches of the U.S. military throughout the years, including during its days under the Thiokol brand.

As for a total production count, the records are unclear and our best guess is around 400. The company would later attempt to bid on one of its largest government contract ever, a procurement request from the U.S. Army for up to 800 Small Unit Support Vehicles. It failed to win the award, prompting Utah Senator Orrin Hatch to intervene. A letter addressed to U.S. Army Secretary John Marsh from Senator Hatch complaining about the decision revealed that DMC-Logan had previously built “approximately 500” vehicles for the government, 92 of which were tracked units—this leaves just over 400 units unaccounted for, a number which several of DMC-Logan’s former employees believe add up to the number of T-40s produced between 1981 and 1982.

Signs of Trouble

There’s another reason why DeLorean expanded into aircraft tugs: DMC-Logan hadn’t been quite the financial windfall he expected. Thanks in part to the 1980s ski boom, snowcat competition began to heat up. Companies like Bombardier and PistenBully were knocking on DMC’s door, and the company began to look into ways to increase cash flow. And as a business with seasonal demand, the company regularly operated at a loss for the majority of the year, according to David Smart. Under Thiokol’s ownership, the Logan plant was able to use its parent company as a banker and stay operational while focusing its spending on raw materials, labor, and product development. When ski season came around, the company would rake in the cash, more than making up for its losses.

When the company split from Thiokol, the blank check funding stopped. And as DeLorean’s own financial and legal troubles multiplied, DMC-Logan would be left to figure out a way to stay afloat with no emergency cash-filled life preserver. Soon the company resorted to taking on odd jobs to stay above water. Its 60 percent market share dwindled through the ’80s as the company pumped out odds and ends like treadmill frames to skid steer loaders.

“There was really no plan to address and modernize, and really bring our product up to what their competition was doing,” said Smart. “[Competitors] had the money to modernize their products more than us. We tried to do the best we could with the limited amount of engineering and R&D that we could do. But John, he wanted money. He took the money out of the company rather than put money in.”

On the outside, this looked like nothing more than a company diversifying its product offerings. In reality, it was the beginning of the end, something that came at no surprise to DeLorean’s personal friend Ken Koncelik, who also happens to own an aircraft tug. Koncelik told me DeLorean was always looking for the next big thing. Once he figured out that he could in fact do or build whatever it was he had put his mind towards, he would move on to a new focus. Perhaps this was DeLorean’s fatal flaw—always wanting more, never satisfied.

DeLorean eventually stopped visiting DMC-Logan, instead sending his colleagues Roy Nesseth and Al Rapetti to handle the day to day operations. Nesseth gained a reputation throughout the years as DeLorean’s enforcer, even on the DeLorean Motor Car side. Employees soon realized why he had this distinction and some referred to him as a “corporate seagull” who was responsible for tapping workers on the shoulder to speed up production, then leaving. On his way out, Nesseth would reportedly empty the cash register and leave a corporate car in an airport parking lot for someone else to retrieve later.

DeLorean’s Debts Catch Up, Big Time

DMC-Logan’s general manager at the time was Gus Davis, a personal friend of DeLorean’s and transplant from Harley-Davidson following his stint as President during its AMF years. In 1982, he soon became tired of dealing with Nesseth and it became clear that purchasing Logan from DeLorean was the only way to save the company from its own foreseeable demise.

Davis contacted Citicorp (now Citigroup) to fund the purchase, who in turn reached out to an investor and Logan native named Kenneth Tingey. Tingey and his partner Thomas Gephart would later form a capital venture called Ventana Growth Fund, but one of their first deals as a partnership was one that could’ve saved DeLorean from himself and potentially changed the course of automotive history.

After visiting Logan and performing financial due diligence, the pair was able to secure an offer to cover both equity and debt. A number was penned—$19 million cash—and sent to DeLorean’s desk. Finally, in late October, they got a response.

“We get a call in the office, John’s directly calling Tom, my partner. And [John] said, ‘Deal’s off. I’m not interested.'” Tingey told me, still shocked nearly 40 years later that DeLorean would turn down a huge sum of cash. “All he had to do was sign it, the deal was done. And it would have been $19 Million cash. [John] says, ‘I’m not I’m not going to sign it. I’ve got another source of money.'”

“So that night, I’m watching TV. And lo and behold, that same night, five hours later, he gets picked up at LAX with the cocaine. That was the same day.”

On October 19th, 1982, John DeLorean was arrested at a Sheraton Hotel near the Los Angeles International Airport. U.S. authorities would charge him with conspiracy to obtain and distribute $24 million worth of cocaine, and by the next day, DeLorean’s story was on the front page of every major newspaper.

His car company was seemingly erased overnight—John placed blame on the British government, accusing them of forcing DeLorean Motor Company out of business by tossing the DMC-12’s $18 million body dies into Galway Bay. Meanwhile, Tingey wanted to bring the details of the buyout to prosecutors in an attempt to push forward Gus Davis’ purchase of Logan, and perhaps save DMC-Logan. His partner Gephart declined, a move which Tingey believes was driven by Gephart’s fear of Roy Nesseth.

“Five or six days later, [DeLorean] came out and had this huge Bible he’s carrying,” said Tingey. “I said to my partner, ‘You know, seems to me, like somebody gonna want to know that this deal is out there’. I think [Tom] was afraid of Nesseth. He’s not alive anymore. But he said, ‘Oh, no. We’re not going to mess with that.'”

The arrest would begin years of legal battles and turmoil for DeLorean, spilling over onto family, friends, associates, and companies that the aspiring auto mogul was affiliated with, DMC-Logan included. DeLorean Manufacturing Company was renamed the Logan Manufacturing Company seemingly overnight. One worker who was around for the transition recalls that the change in name was partly driven by customers who refused to work with a company that brandished the DMC branding following John’s cocaine scandal.

Below, you can see a video of a 1985 LMC 1500 snowcat. The headlight design might look familiar.

For the next decade, DeLorean’s properties were the focus of creditors who attempted to collect debts from the failed automaker. Some argued in bankruptcy courts that LMC should become the property of the creditors who John was indebted to for millions of dollars, while DeLorean contested the ownership. Meanwhile, DeLorean’s own lawyers argued that they had not received payment to represent him in his federal drug case. Eventually eyes were also turned to DeLorean’s 48-acre avocado and citrus ranch in California, which, according to his son Zach, made up the majority of DeLorean’s personal income when paired with LMC.

LMC Gets Left Behind

By the late 1980s, employees could plainly see LMC entering a death spiral. Some, like Gus Davis, left the company in search for more stable employment. Many who joined him in leaving began working at competitors and other started their own businesses using the skills they learned while at LMC. Regardless of when they jumped ship, many still blame DeLorean’s dealings for the company’s eventual demise, saying that he saw the company as a meal ticket instead of the family-run business that it felt like at the beginning.

“[LMC] was a great company to work for. We were all like family, close knit, if that makes any sense.” said former LMC employee Keith Laursen, recalling his stint at Logan towards the end of his 13 year run with the company. “I still talk with the people I used to work with—there’s a lot of us [who] wanted to make it a long life with the company but at the end, all the money was taken out and nothing was getting put back in. So when our checks would come, we would go immediately to the bank to make sure that they would cash.”

David Smart recalls receptionists beginning to field calls with angry suppliers looking to collect on debts LMC owed to them. When not on the phone, they were opening mail addressed to the company in hopes that a check made out to LMC would arrive that day. It was their job to collect all incoming funds and immediately bring those to accounting to be deposited, presumably to keep the lights on and the employees paid.

Others recall sticking in out in hopes of retiring from the company they loved, only to learn that DeLorean had stopped matching the employee retirement contributions they had been receiving while the company was still under Thiokol.

“John had charisma and charmed us all,” Karole Roskelley Sorensen said. “We were had. We had no idea that things would go downhill in a short time. He drained us of our funds and called us a ‘[cash] cow’.”

That term—cash cow—was one I heard often in talking to former employees. It became apparent that DeLorean was fairly hands-off when it came to the day-to-day operations of the company, leaving the workers with something they desperately needed to grow: a leader.

“[DeLorean] didn’t provide really any leadership, nor did he give us any money to operate on. It was all a cash cow for him,” Smart said. “I saw it from the inside handling the capital acquisition. And I saw the before and after. It was almost like the day he bought [LMC] it was full-speed-zero-rudder. You hit the throttle and the boat just goes wherever it wants to go, there’s nobody guiding it. That was the feeling we had as the company.”

In December 1992, DeLorean finally sold off LMC for $12.75 million. Following the asset purchase agreement, DeLorean renamed LMC to “ECCLESIASTES 9:10-11-12”, a move which news outlets like The Guardian speculated was strategically timed to delay collections from the hundreds of creditors around the world could who sought collection against debts owed by DeLorean. To make matters more complex, Ecclesiastes had just one shareholder: DeLorean Manufacturing, which was a company with just a single shareholder, a corporation called “Cristina” (named after DeLorean’s wife). Cristina’s sole owner was, you guessed it, John Z. DeLorean. The sale was full of complexities and was the subject of a legal battle which carried on past DeLorean’s death in 2005.

LMC finally met its fate in April 2000 when it filed for bankruptcy. Declining business during the ’90s and increased competition in a niche market eventually caused the company to close its doors. The factory was demolished sometime between 2007 and 2009, but you can still see the outline of the the T-40’s test track, which the earth has yet to reclaim.

As for what could have been, look no further than that ski lift business Thiokol parted out at the same time it sold the snowcat operations to DeLorean. It was bought by former Thiokol employees Jan Leonard and Mark Ballantyne, who took charge and formed the Cable Transportation Engineering Corporation. The pair steered the business to success amid the ’80s ski boom before merging with famed Swiss ski lift maker Garaventa in 1993, then again in 2002 with an Austrian company called Doppelmayr. Within 25 years it had become one of largest ropeway manufacturers in the entire world, with Jan Leonard as the president of the company’s North American division.

And DeLorean Manufacturing Company? It’s an empty corner lot.

Got a tip or question for the author? You can reach them here: Rob@thedrive.com