Most places look like somewhere else. Erase the inky bursts of Korean pine, and the road northeast from Incheon to Seoul could be one of the wide asphalt ribbons that snakes its way through the German Eifel, framed by low dark mountains and hung with fog. The flat light and dun-colored hills that fill the windows during a midwinter climb into PyeongChang could be mistaken, at a glance, for central California. More than proportion or terrain, it’s the traffic that identifies a South Korean highway—a colorless arterial flow of black and white and gray Hyundais and Kias, and very little otherwise, everywhere you go.

Two years ago, Hyundai Motor Company outsold BMW, Daimler, and Mazda combined. In 2017 the Company—which includes Kia, Korea’s second-largest car manufacturer when it was purchased in 1998, and Genesis Motors, Hyundai’s luxury-vehicle division until 2015 that has since become a standalone marque—missed its global sales target by one million vehicles. That dropped Hyundai from the world’s third-largest automaker to fifth, behind Renault-Nissan (newly gargantuan thanks to the ingestion of Mitsubishi), Volkswagen Group, Toyota, and General Motors. But the company’s reach remains impressive: despite its worst sales year since 2012, the company last year shipped 7.25 million cars to over 160 countries. The Hyundai Motor Company is just one part of an exponentially larger chaebol—a family-run conglomerate—called Hyundai Motor Group, which owns or controls interests in the steel, insurance, heavy machinery, finance, construction, engineering, mining, and even sports management industries; it is the second-largest chaebol in South Korea, behind Samsung, and reports an annual revenue in excess of 200 billion dollars. When Hyundai Motor Group makes a decision about its cars, from preferred tire brand to the market viability of hydrogen-powered electric vehicles, it becomes the de facto choice of the South Korean automotive industry.

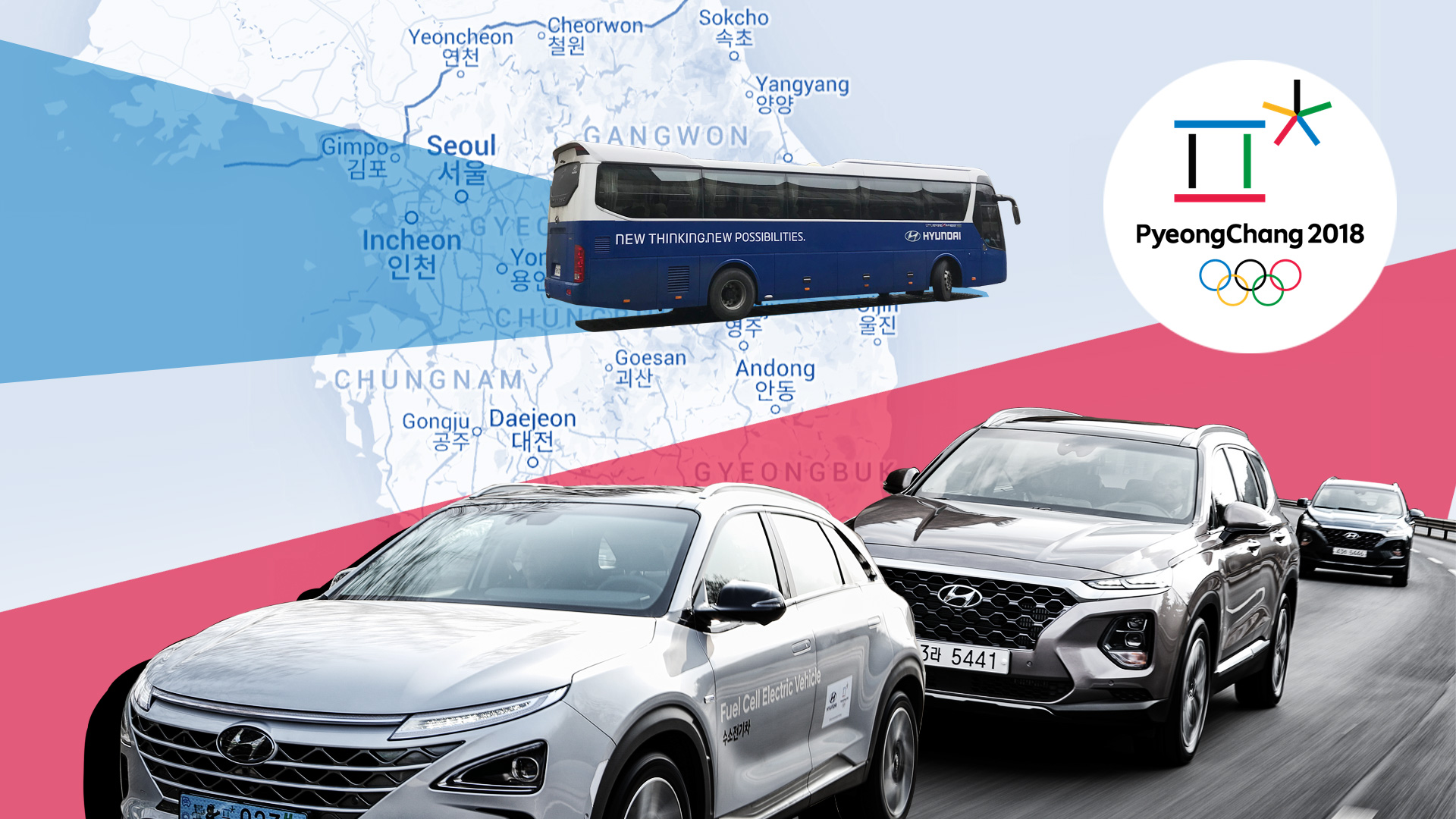

In late February, Hyundai hosted a grueling three-day event (closer to six days when including travel from the U.S.) to launch a pair of crossovers: the updated 2018 Santa Fe and the all-new Nexo, a next-generation fuel-cell electric vehicle that follows the Santa Fe Tuscon FCEV, which in the U.S. was available only as a California lease. The itinerary included visits to Hyundai’s Motorstudio Goyang, a 690,000 square-foot exhibition space and automotive theme park; to Olympic Village, in PyeongChang, for a demonstration of Level 4 self-driving technology in a prototype Nexo; and two distinct press drives, on separate days starting in different parts of the country, of several hours each.

2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

The only way to describe the full Korean press-trip experience is to note that it is nearly identical to the Japanese version, which is to say an extremely polite death march: 14 hour days scheduled down to 15 minute increments; transferring daily between cars, buses, and trains; and changing hotels nightly. Journalists are fed often and well, and are alternatively fussed over and transported like freight, all while being randomly captured by a stealth cadre of photographers who materialize to document moments like stepping from a bus, feigning interest in a lengthy PowerPoint presentation, or chewing a piece of steak. The experience creates the disorienting feeling that you’ve become a celebrity’s pet, mostly cared for by a team of handlers.

The whole show serves as a highly-choreographed form of brand proselytizing: to Hyundai or Toyota’s or Subaru’s thinking, fully understanding any car is only possible by first comprehending the corporate culture that created it. It’s also worth noting the subtext to these types of tours, which impresses upon the observer the absolute precision necessary to execute such an enormous logistical lift—out-German-ing the Germans, as it were.

A good example was the drive-by attendance of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games, which lasted exactly 90 minutes. (The full itinerary for that day, which also included a bus ride, a train ride, a surprisingly funny presentation on Hyundai’s rail division during said train ride, and a hotel transfer, was listed on page eight of the 18-page trip handbook which was received by email several days prior.)

I was told by a Hyundai representative that the Olympics were not on the original itinerary, but as the Games were underway in PyeongChang, South Korea’s preeminent carmaker ultimately felt duty-bound to share in the national celebration. (In a sly bit of corporate judo, Japanese rival Toyota maintained official automotive sponsorship rights for the 2018 Winter Games thanks to an exclusive 10-year deal, worth a reported $835 million, signed in 2015.) This required the guiding of nearly 70 American, Canadian, New Zealander, and various European journalists into vast rows of stadium seating arranged on a shallow valley floor. An immense lip of manmade snow towered in the near distance; higher still, 160 feet off the ground, a small hut perched atop the ramp, marking the start of the in-run for Men’s Big Air snowboarding. A slow procession of tiny men dropped in from on high, picked up speed, and disappeared briefly from view before a colorful little astronaut launched overhead, spinning and flipping in the air like a thrown propeller before touching down into a smooth glide. One would occasionally miss the landing and shovel himself into hard powder, the flat slap and rough scrubbing of abraded nylon echoing off the mountain.

And then the allotted time was spent and we were up, out of our seats, Hyundai team members encircling us like cattle dogs and moving us out of the stadium and onto a bus and on to the next event.

Hyundai Nexo Prototype With Claimed Level 4 Autonomy

A fleet of Hyundai’s enviable hydrogen-electric luxury buses—I’ve seen nothing like them in America, which doesn’t much cater to luxury bus tours—shuttled the group a short ride away to a branded pavilion in Olympic Village, which was the starting and ending point for Hyundai’s demonstration of its most advanced self-driving technology. The exhibition consisted of a roughly four-mile loop around the stadium and Olympic Village, which was surprisingly expansive. Never having been to an Olympics, I naïvely pictured it as some relentless, centralized orgy of sport, but the Winter Games are a sprawl if for no other reason than mountains are colossal things. Their steep angles are also confusing for self-driving cars, both because they limit visibility and due to the fact that human drivers prefer to accelerate up and decelerate down hills—counter-intuitive, maybe, to a machine’s logical point of view.

This would not be my first autonomous rodeo, having put 20 hours of surprisingly ungrueling work over the course of two days between Memphis and Santa Fe in a Cadillac CT6 with Super Cruise. GM’s hands-free system is shockingly good, but the Nexo prototype’s capability was a categorical difference, purportedly able to navigate itself from A to B with just a few coordinates and the push of a button. (Two Hyundai engineers accompanied the ride, one in the driver’s seat and the other in the rear, but a language barrier hampered efforts to gather detailed information.) The car certainly had an abundance of hardware: four radar units; six LiDAR sensors front and rear; cameras to pick up signs and lane markings and possible obstructions; and the ability to input traffic light information from the local infrastructure network via a 5G data connection. From the passenger seat, I watched the hypnotically soothing LiDAR display sketching the objects that came into the car’s orbit, the detail increasing with proximity in real time.

Ten minutes into the trip, flowing in an ooze of traffic, the Nexo had what would be categorized in the autonomous-systems world as an “incident”: The system bricked itself after a full panic stop, the result of being relentlessly squeezed by a large bus merging with the unhurried pace of a drifting boat. (This, I observed later, is the typical merging speed for drivers in South Korea.) The bus driver, a human, started the lane-change with the Nexo close to the larger vehicle’s midway point, meaning the Nexo had the right-of-way. A human driver likely would have recognized the bus driver’s intention to merge regardless of law or decorum—in the real world, sometimes big vehicles decide they are going to change lanes and that’s all there is to it—and aggressively sped up or slowed down to accommodate. But neither would anyone fault a person who slammed on the brakes in a fit of frustration—which is essentially what the Nexo did.

Shortly after the restart, a more challenging scenario presented itself: the Nexo rolled up to a live roundabout, and stopped. A few cars passed and the lane was clear. In response, the steering wheel twitched robotically like a Max Headroom stutter. The car stayed put. Other vehicles appeared in the distance, heading in our direction. Then, calculations presumably complete, the Nexo launched itself with a silent accelerative rush into the infinite corner, the wheel locked half-tilt, before picking its way to the outermost lane toward the exit.

There’s a dissociative feeling to sitting inside a vehicle and watching it drive itself, like a lingering ketamine high coming back from anesthesia. The car still looks and moves and squeaks in the familiar ways. There’s a steering wheel, floor mats, loose change in the cupholders, gas pedal. Beyoncé might be playing on the radio. Humming down a freeway feels the same as it does everywhere—that half-attentive boredom like sitting in a theater waiting for a movie to start in the pre-smartphone era—and the windows are filled with familiar things, trees or hills or asphalt stretching into forever, and 60 mph is no slower or faster than it’s ever been, except sometimes you look over and nobody’s driving the fucking car.

Letting go of the wheel for the first time, too, is a queasy feeling, but I’ve developed a surprisingly quick if incomplete trust in these machines, mostly because it’s immediately apparent how few and small are the inputs needed for the average commute. The skill to drive both fast and well may be a lifetime’s pursuit bordering on the artistic, but highway driving is mostly so simple it can be handled by the average American between text messages. Still, watching a car navigate itself through a series of hard turns, steep hills, merges, and a live roundabout, as the Nexo did, made the true self-driving future feel very close and tangible indeed.

But appropriate to the Olympic setting, a potential doping scandal came to light after the high-scoring performance. As one journlist exited the vehicle after the demonstration, he asked almost as an afterthought whether the route had been programmed beforehand. The pair of engineers had a short conversation in Korean.

“Yes,” said one of the engineers, and then briefly conferenced again with his partner. “For safety?”

Such pre-programming would negate a demonstration of true Level 4, though something very well may have been lost in translation. Before the issue could be resolved, we were corralled again onto a bus and in motion.

The Hyundai Nexo Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle

The day before we had been driving the Nexo ourselves, like suckers. Given the still-exotic nature of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles, at least in the U.S.—I’ve driven more Ferrari models than FCEV—anyone who’s driven a battery-electric car will recognize the basic EV driving signature: a launch off the line or while passing from instantaneous low-end thrust, plus spongey regenerative brakes. The Nexo made reliable and pleasant work of the freeway, despite a low whistle of wind and audible tire scrub from the high-efficiency rubber, the silent hydrogen fuel-cell system making both easier to hear. The exterior styling prioritizes personality over balance—the character lines all dive and kink and swoop before gracelessly slamming into one another—but the retracting door-handle feature, like that found on a Range Rover Velar, adds a bit of elegance by subtraction. Inside is airy and comfortable, an exemplary execution of the Price-Point Futuristic aesthetic: wide, flat, slightly canted surfaces that intersect like furniture jointing; bright whites and grays; too many buttons; and a prominent infotainment touchscreen.

The lowdown positioning of the electric motor and fuel cell also help plant the car into the road: this begins and concludes my notes on the car’s handling. Aside from a slow roll through Seoul’s overflowing Itaewon neighborhood, the fuel cell-electric crossover saw nothing but straight highway. It was probably for the best. The Nexo is a competent and distinctly pleasing commuter crossover, attentively built for those who want comfort and basic utility and especially the feeling of having made a savvy choice in an environmentally-friendly, technologically advanced alternative-fuel vehicle that’s packed with content and requires little sacrifice. (And if they’re Americans, those who also: live in California, and are willing to lease. The Nexo might be a production car, but in America it remains a proof-of-concept.)

What might be most notable about the Nexo is the way in which it fits into Hyundai’s alternative-powertrain lineup, which is to say it’s an ensemble player: Hyundai Motor Company—and, therefore, South Korea—remains diplomatic amid the world’s splintering zero-emission factions. Hyundai currently offers hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and battery-electric vehicles, and hydrogen fuel-cell EVs, and the South Korean auto industry’s plan to pursue a broad portfolio of zero-emission vehicles stands in contrast to neighboring Japan, a country currently rushing to rebrand itself the Hydrogen Society, and China, the world’s largest producer of battery-electric vehicles in part because the Chinese government is determined to win what it considers an arms race for battery-powered EVs, and therefore insists on its own domestic demand.

This impartiality is societal as much as commercial, says Sohn Yong, general manager of Hyundai’s global PR team. “South Korea is a very open culture—and very open to the West,” he told me over lunch one day. Yong is lanky and gregarious, with glasses and a flop of jet-black hair above a boyish face that he offsets with dark banker’s suits. Yong studied and worked in the U.S. for several years, though has since returned to Korea, which he paints as a vibrant and curious culture. “We are not so insular, like Japan or China,” he told me.

But as with both of those countries, an indigenous driving culture and the homegrown auto industry that developed in tandem are both relatively new phenomena. While Korean culture is ancient, modern South Korea only dates back to 1948—the inaugural Indy 500 preceded it by 37 years—and driving on a mass scale has only been a reality for the last several decades, which is not long when one considers the gestation period for a new vehicle can take up to six years. The Korean automobile industry didn’t produce a domestic model until 1975; that car, the Hyundai Pony, was mostly developed by Sir George Turnbull, of British Leyland Motor Corporation, who was hired as a vice president the year before and who subsequently poached a quintet of Brit engineers to work on the car, which also become Korea’s first automotive export, in 1976. The Pony had an engine and transmission from Mitsubishi, a 15.3-second meander to 60 mph, and, surprisingly, a muscular design penned by Giorgetto Giugiaro, of Italdesign fame. The car stayed in production for the next 15 years, adding pickup- and estate variants along the way. Its lifespan ran parallel to a massive boom for Hyundai, and the Korean auto industry as a whole: by the time the Pony was retired, in 1990, Hyundai was exporting one million vehicles to the U.S. alone.

Hyundai Motorstudio Goyang

Hyundai opened its new Motorstudio in Goyang, a satellite city ninety minutes northwest of Seoul by hydrogen-powered luxury bus, in 2017. Conceived as an educational hub for Korean car culture, the space was designed by Vienna-based architects DMAA and would encompass more than half a Manhattan city block. There are animatronic displays mimicking steps in the car-making process, like stamping a steel hood, painting an exterior, or installing a seat—all performed, as in real life, by a robot—much like you’d find in an automotive museum in Detroit or Los Angeles, but modern and with slick features. A series of rooms lead guests progressively through the basic stages of automotive design and manufacture, from concept to clay model to finished product, utilizing sleek touchscreen displays and several installations that can only be described as conceptual art that is vaguely car-related. The tour was full of Instagrammable moments and in total conveyed roughly as much information about automotive manufacturing as a children’s pop-up book, which likely explained the group of uniformed schoolchildren quietly chasing one another through the lobby as we waited for the tour to begin.

The architectural brief for Motorstudio called for a meditation on Hyundai’s “Modern Premium” strategy, which defines quality as the combination of technology, functionality, design, comfort, and sustainability. “Performance” did not make the cut.

2019 Hyundai Santa Fe

As per the itinerary on page seven of the Hyundai Media Experience guidebook, the Santa Fe press launch began with a scheduled hourlong presentation, mostly in PowerPoint, in a cavernous events hall at Motorstudio Goyang. The 2019 Santa Fe is a significant vehicle for Hyundai in the all-important large crossover category, and the presentation was interminable—millimeter adjustments to seat placement were covered with the same care as engine specifications, and the number and placement of in-vehicle water bottles and gum packs for the test drive warranted its own slide—though I developed an awed respect for the succession of South Korean engineers dutifully attempting to relay technical minutiae in English, a language clearly still mostly foreign to them, with the determined stammer of a bar mitzvah translating the Torah; one had the sense it was a high-wire performance not for the journalists, but the bosses. As always, we departed on time, but with the unique caveat to pay special attention to the GPS given that the winding route would at one point put us within 10 miles of the North Korean border—a jarring reminder that South Korea in the second month of 2018 was dead center in the middle of a nuclear-tinged geopolitical pissing match. None of our Korean hosts, nor anyone else I encountered, seemed particularly upset by this.

I distinctly remember the Santa Fe’s streamlined and surprisingly posh cabin and butch exterior styling, like an apprentice Land Cruiser. Mostly I remember the harmonious uproar of pings, tones, alerts, warnings, buzzes, and non-sequiturs that filled the cabin with anxiety like rising water. The car tried to communicate everything going on in and around it, all at once. I told the Hyundai representative riding shotgun that if I owned the car I would immediately pull it over to the side of the road and burn it to the ground, even though it seemed very pleasant otherwise. He laughed nervously and pointed out that it was a Korean-spec car, so many of the alerts wouldn’t make it to the U.S., and could also probably be turned off, which is very likely true.

But if you’re in Korea driving a new, Korean-spec Santa Fe, it will ping if it senses another car is too close, and bong if there’s a traffic camera ahead—there’s always a traffic camera ahead—and weepweepweepweep if another car hits the brakes ahead of you, and chirp if you’re drifting out of your lane. As all the sounds shout for attention a soothing voice nags you non-stop with everything from the banal—”A speed bump is ahead;” “Stay alert for jaywalkers”—to the cryptic (“High collision area ahead”) to my favorite, the inscrutable: “Be careful of left curve.” If you speed it will beep with a particularly irritating cadence until you drop below the posted limit. Not back to target, mind you, but below it; if you dare speed, the car will punish you until you’ve made amends.

After several hours of prolonged and painful exposure therapy I wanted nothing more than to climb into a plane seat for 14 hours back to New York City, where things are quieter. The trip was mostly over at this point. The only items left on the itinerary (page 11 of the guidebook) was a rowdy dinner of traditional Korean BBQ—late in the evening I watched an otherwise muted Hyundai executive drop a shot of soju into a half-pint of beer, top the glass with a napkin and shaker it into a whirlpool, before sticking the soaked napkin to the ceiling with a hard throw and attempting to chug the beer before the napkin fell, which he did easily—and, for me, most of the next day to wander around.

I spent the afternoon getting lost in the steep and mystifying warren of tiny shops and karaoke bars and minuscule restaurants that make up Itaewon. I was struck by the fact that one can’t escape free WiFi in Seoul—it might as well be a by-product of the air—and I remembered something Sohn Yong had said to me a couple days earlier, about the misperception many Americans have that the U.S. is the most technologically advanced nation in any given area simply because, well, it’s America. In fact, South Korea is the most wired country in the world, with internet penetration of over 82 percent and more credit card transactions per person than anywhere else. Even the bus stops have digital countdowns. The technological infrastructure that underpins Seoul surpasses anything in America, possibly including Silicon Valley.

South Korea is mad for technology and style, and these are the keys to understanding the over-communicative Santa Fe, or really any Hyundai vehicle. Between Hyundai, Kia, and Genesis, Hyundai Motor company reportedly accounts for around 80 percent of the domestic car market, in a country that has never had a racing or hot-rodding culture to speak of, and where no one ever seems to speed. The only great driver’s car the company has ever produced, the new Kia Stinger, was developed using the time-honored technique of poaching a German chassis engineer. In terms of driving dynamics, Hyundai evolved somewhat like a sloth: high performance was never a consideration, let alone a survival strategy.

Instead, South Korean car-culture enthusiasm seems linked to the country’s appetite for personal technology, which is very much defined by hardware: Samsung, LG, and the other various handset-, device-, and TV makers are both cultural and political forces. It’s a mentality that values the car like a giant piece of hardware intent on notifying you, reminding you, informing you, issuing commands, taking dictation, and otherwise interacting with you as much as possible, learning everything it can about you all the while—the better to serve you, yes, but probably also to sell that data elsewhere, later.

The driving aspect of that sort of car is merely a necessary but unimportant precursor—and besides, it will all be autonomous before long, anyway. Soon, the automotive cabin will be a pinging, boinging cavern of push notifications and status updates and soothing warnings about the dangers of left-hand curves, where you feed your car continuous little morsels of attention like treats to a fussy pet, and in return you’ll be given yet another sanctuary from the quiet and unimposing fact that one day you will die.

This is precisely what the average driver wants, in America as anywhere else, and I am quite happy for him to have it. On a related note, I have decided that once this endless procession of nor’easters quits I’m going to buy a motorcycle.