Randy White was riding along in his automobile, creeping northward across eastern Pennsylvania on his way from his farm in Landenberg to his grandmother’s house in Pine Grove, and he was feeling a bit edgy. Not the kind of edgy that the 6’4”, 257-pound defensive tackle turned when he wore No. 54 for the Cowboys, the kind that made him the most feared pass rusher of his day. No, he was feeling the kind of edgy that mists a man’s bristly mustache and turns his feathery brown hair into a mop of nerve endings when he finds himself alone on a slick, snaking, two-lane mountain pass for 80-odd miles on a cold winter’s night.

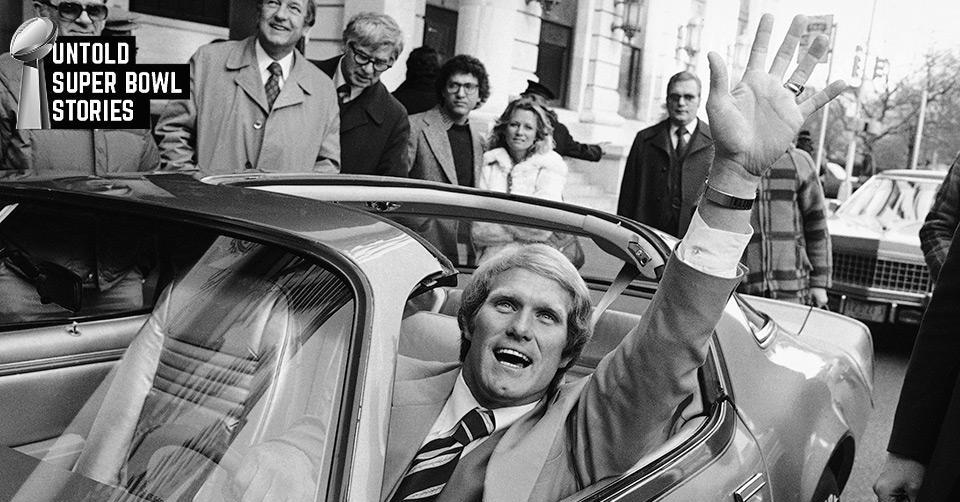

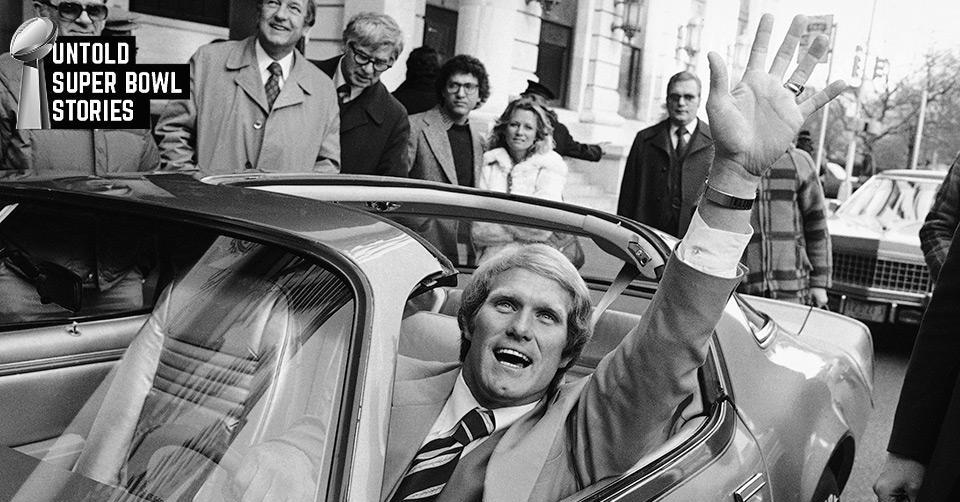

What’s more, White was behind the wheel of a brand spankin’ new, baby blue 1978 Ford Thunderbird. At nearly 18 feet long—or about the distance it would take for White, exploding from his crouch, to brush off a couple blockers and tear into an unsuspecting quarterback—the T-Bird was the land yacht for people with champagne dreams and malt liquor money. White’s car had all the trimmings: power windows, vinyl roof, big block V8. It even had concealed head lamps, clearing the way as White tacked and jibed his way up Route 41. “There were no street lights and you couldn’t see all the sides of the road,” recalls White, now 62. He’s grayer today but still very much a badass, wiling away his retirement years practicing martial arts and crafting hunting knives. “Hell, I was out in the middle of nowhere. There wasn’t a lot of traffic.”

And then, just as he eased into another curve—BAM!—something crashed into the bow of his T-Bird like a cannonball. He screeched to a halt. “I don’t know if you’ve ever hit a deer,” he starts, “but it happens in a flash, like a dream.” The state police seemed to arrive in an instant, then a crowd behind them. White examined the stricken animal. Alas, it did not survive.

The T-Bird? Its front end may have crumpled like an accordion, but it still rattled and clanged its way to grandma’s house. Fixing that racket was not cheap, but White wasn’t bent out of shape over it. How could he be? The T-Bird was a freebie, after all, his grand prize for being named a co-MVP of Super Bowl XII.

***

It is the most routine of handoffs in football. It comes right behind the Super Bowl’s final whistle, after the triumphant team’s owner takes possession of the Lombardi trophy and the winning coach is recognized for, really, steering that transaction. Then, with hundreds of millions of eyes watching, the game’s big hero steps to the fore and a breathless broadcaster tells him he’s won the MVP award, along with—wait for it—a brand new car!

Of course, this act is as much a staple of other pro sports. But it took the Super Bowl, America’s biggest game show, to elevate this promotion play from standard product placement to the ultimate jackpot moment—a “win-win-win deal,” as Joe Namath, MVP of Super Bowl III, puts it. Yet for all its significance—“the icing on the cake,” says Doug Williams, MVP of XXII—the moment is often lost on viewers amid all the agony and the ecstasy of, you know, the game itself. The players who ride off into the sunset with a new set of wheels, though? They remember.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I expect to win anything like that,” says White. “It was a big deal.”

And that was in 1978. Imagine what a free automobile meant to a player 23 years earlier, back when the tradition was started by Sport, a now-defunct magazine that predates SI by almost a decade. In ‘55 the monthly publication started naming a World Series “Top Performer,” as voted on by its editors, and along with General Motors they gave each winner a Chevrolet Corvette. That year, the first set of keys went to an unheralded Brooklyn Dodgers lefty named Johnny Podres, and his Vette was a beaut—cream-colored on the outside, red leather on the inside, with 195 ponies that could bring that baby up to a top speed of 140 mph. “I’ll tell you,” Podres told the reporters and photographers who came to see him receive his hand-off at Dodgers Stadium, “I’m sitting on top of the world.”

After Podres, four more World Series-winning hurlers would take possession of new Corvettes before Sport added another Top Performer award (later renamed the MVP) for the NFL championship. That ride, a fire truck-red number, went to “me,” Johnny Unitas told Sport—“another pitcher.” Since Unitas’s Baltimore Colts vanquished the Giants 23-17 in a December 1958 overtime thriller that carved pro football’s place into the national lore, Sport’s little car club has grown into quite the scene.

Naturally, the party didn’t really get started until Namath, yet another pitcher, joined the club in 1969. His reward for piloting the Jets to a 16-7 upset over Unitas’s mighty Colts in that year’s NFL championship—the first to bear the name “Super Bowl”—was a shimmering blue Dodge Charger R/T, the first non-Vette ever handed off. And with it: a gift tax. “That’s why I call the MVP car a win-win-win,” Namath explains. “Even Uncle Sam gets his cut.”

Ask the 72-year-old Hall of Famer about that car today and his thoughts turn to his mother. Rose Namath was still a proud and soft-spoken woman when the youngest of her five children became the king of New York and the toast of the nation. She had managed to go 60 years without owning a car. Making the Charger her first—even though, her son says, “you wouldn’t see a mom driving that kind of car, normally”—seemed like a good idea. The catch: Rose didn’t know how to drive. Joe left the nervous job of teaching her to his older brothers while he went off on a USO tour. When he returned a month later to his hometown of Beaver Falls, Pa., Rose insisted on taking Joe for a ride downtown to the market. The five-minute journey—over a two-lane, downhill stretch—felt like a ride on a rickety old roller coaster from where Joe sat. He can still see his mom pawing at the wheel, still hear that V8 snarling, still feel that land yacht rocking. “Even though she was going about 20 miles an hour, I was sweating it, holding on,” he says. “Mind you, she did get downtown. But when we got parked, I told her, ‘Wow, mom. That was terrific and all, but please let me drive you back.’”

Namath was among the first in a long line of re-gifters. Packers quarterback Bart Starr, MVP of what we would retroactively come to call Super Bowls I and II, donated his second Vette to an auction in order to raise money for the Rawhide Boys Ranch, a Wisconsin home for at-risk youths. Audrey Smith, mother of Seahawks linebacker Malcolm Smith, the MVP of Super Bowl XLVIII, basically called dibs on his ride after the final whistle.

“Did you see the car out there?” said Audrey, her eyes lighting up over the 2014 Chevy Silverado parked on the field.

“Yeah, I did,” Malcolm said. “Do you like it?”

“Yes.”

“O.K., you can have it!”

When the Cowboys won Super Bowl XII and White, along with defensive end Harvey Martin, became the game’s first co-MVPs, there was a moment when it seemed as if the two men might be drawn into some sort of Solomon moment, as if they’d have to choose who got the T-Bird—or watch it be cut in half. But word soon came down that the folks at Ford would furnish two. “It was not one of my goals to get the most valuable player in that game and get a new car,” White says. “But it certainly was a great honor.”

Not everyone expressed such unabashed appreciation. When Dallas won its maiden title, at Super Bowl VI in 1972, Roger Staubach, the Cowboys’ MVP-winning QB, shrugged. Informed that he’d just won a Dodge Charger, he asked for a station wagon instead. “We had three kids,” he says now. “What was I going to do with a Dodge Charger?”

Dolphins safety Jake Scott, the MVP of Super Bowl VII, traded in his Charger, too—but only because he already owned one. Dodge let him have a Ram pickup instead. One year later, when teammate Larry Csonka won himself a Charger at Super Bowl VIII, the Miami running back became the first MVP selected by the Pro Football Writers’ Association, which had taken over the process. Much later, after the internet became a thing, fans got a vote too, one that counted toward 20 percent of the ballot. Sport still kept its stamp on the award, though, and at Super Bowl IX the magazine co-presented with American Motors Company, which allowed MVP winners their choice of any vehicle in the company’s range. Steelers running back Franco Harris, the hero of that game, opted for a Jeep Cherokee. “I had it for many years,” he recalls, “but eventually I had to let it go.”

Williams, the first black quarterback to win a Super Bowl, in 1988, had hoped to hold on to his MVP ride for a while. The only reason he didn’t: That year’s sponsor, Subaru, was giving away an XT coupe, and that car, while sleek and quick and burgundy-colored—“same as the Redskins,” Williams says—wasn’t nearly as big and roomy as the many land yachts passed down before it. And this posed a problem for the 6’4” QB. “I drove it for about six months,” he says of the Subie. “Then I signed it over to my brother, who probably drove it for eight years. I wish Subarus were as big back then as they are now.”

It was right around this time that the wheels fell off at Sport. Unable to stanch financial losses that dated to the mid-1960s, the magazine changed hands, from one publisher to next. Jerry Rice, the standout of Super Bowl XXIII, was the last MVP to be recognized by Sport, which was finally bought by a group of investors in 2000, and then shuttered. (The company has since been reimagined as a purveyor of reproductions of the old magazine’s archival art.) “Oh, wow,” the wideout sarcastically said upon claiming his prize—“a Subaru.” Like many stars of his day, Rice was rather well-compensated and had the garage to prove it. “I’ve got so many cars,” he continued. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with a Subaru. Maybe I’ll give it to my mom.”

Since Unitas took the keys to that Vette 57 years ago, every Super Bowl MVP has won a car, save for one. In 2010, Saints quarterback Drew Brees (XLIV) was the victim of a global financial crisis that hit the auto industry particularly hard. Giving away product wouldn’t have been a good look.

And then there’s Malcolm Butler, the Patriots cornerback who was not named the game’s MVP last February, but who nonetheless came away from that game with a brand new truck.

***

Not long after the confetti fell on Super Bowl XLIX, a 28-24 result that was decided when Butler intercepted a slant pass—intended for Ricardo Lockette—in the end zone, the reserve cornerback started hearing whispers that Tom Brady was going to give him his MVP ride, a 2015 Chevy Colorado pickup. Butler couldn’t believe it then—and he couldn’t believe it three days later, after the championship parade in Boston, when the quarterback strolled across the Patriots’ locker room and tossed him the keys. “That blew me away,” says Butler. “It was the ultimate sign of respect.”

It was also a sweet reward for a player unaccustomed to receiving them. A college football vagabond with two tours in JUCO, one in Division I-AA and yet another in D-II, Butler had joined the Patriots that preseason as a 25-year-old undrafted free agent, for a signing bonus of naught. When he reported to training camp and pulled into a parking lot full of precisely the kinds of cars you would expect, he did so in a blue 2007 Chevy Yukon (odometer: 96,000 miles) that he’d bought for $10,000 from “a friend of a friend.”

That Chevy was the first car Butler ever bought and his most extravagant purchase to date. That is, until the Colorado. After Brady tossed him the keys, there was the little matter of the gift tax. When Brady politely declined the car—not only because he’d won two already, but because, he said, Butler was more deserving—it fell to the rookie corner to settle the tab of roughly $12,000. That became easier to stomach after Butler pocketed some $160,000 in postseason bonuses. “Where else,” he says, “can you get a brand new car for just the taxes?”

Butler drives his new Chevy every day, everywhere now, while the old one gathers dust and sentimental value. And he still gives it that new-car treatment. “I did not have a lot growing up,” says Butler, who was raised in the low-income, western-Mississippi town of Vicksburg. His mother, Deborah, taught him to “take care of my things.” Which explains his policy against passengers bringing food or drinks aboard the Colorado: “It’s not a museum, but it’s not a cafeteria either.”

Tell Butler about the time Randy White hit a deer with his MVP ride and he asks, “Is Randy O.K.?” (Yes.) “Did they give him a replacement?” (No.) “Did he have insurance?” (Yes.)

But tell Butler that at Super Bowl 50 there might not be a car given out to the MVP and he won’t believe that. The thing is, it’s true; the league’s plans are still up in the air. In June, Hyundai was named the NFL’s new official automaker, but the South Korean carmaker’s agreement with the league, mystifyingly enough, does not include a provision about presenting a Tucson or an Equus at the end of the nation’s most-watched event. And while, yes, it would be weird for America’s game to end without someone off-loading America’s greatest commercial product, it would also be a sign of the times. Even the 53rd man on either team’s roster makes life-changing money. And a car? Isn’t that what Uber’s for?

Really, though, “any [prize] would be O.K.,” Butler says, “because you won and nothing can beat winning the Super Bowl with your teammates. That’s the gift they can’t take away from you.”

Still, if it were up to him to choose a new prize? “I guess a plane wouldn’t be bad.”

—

This article is one in a series during the lead up to Super Bowl 50. You can find the rest here.