“We met at a party in London,” recalls Aisleyne Horgan-Wallace of her introduction to Bo Eriksson. “He was nice, but he was very flashy. He bought, like, 10 bottles of Cristal and we ended up going to his associate Joe Martin’s unbelievable house. It was huge, with massive pieces of art, ponce and posh. It was something you’d imagine Michael Jackson to have, or Madonna.”

The striking blonde Horgan-Wallace was a staple of the UK tabloids, best known for her stint on the British Big Brother. In the early 2000s she was a fledgling model who’d just signed to Isis Models, a successful agency bought out by Eriksson’s company, Gizmondo, and used as a source for “promotions girls” to charm potential investors.

Isis was one of the only companies under Gizmondo’s corporate umbrella ever to show a profit. Horgan-Wallace’s time there was a crash course in excess—noteworthy even in an industry as dissolute as professional modeling. “I’m a girl of the world,” she said. “I know street criminals, and I always thought [Eriksson and Freer] were very professional and all that, but way too flashy for what they did. They just had a swagger about them that said there was something dark underneath the surface.”

In 2004, Gizmondo opened a high-profile flagship store on London’s exclusive Regent Street. They spared no expense. The rent was $300,000 a year and the store was built to entertain: top-to-bottom black marble, $750,000 worth of state-of-the-art 3D TVs, $48,000 of Bang & Olufsen phones and cameras, numerous bars, and a sound system worthy of a mega-club. Even the toilets were lined with Swarovski crystals. The men of Gizmondo were literally taking a shit atop their investors’ contributions.

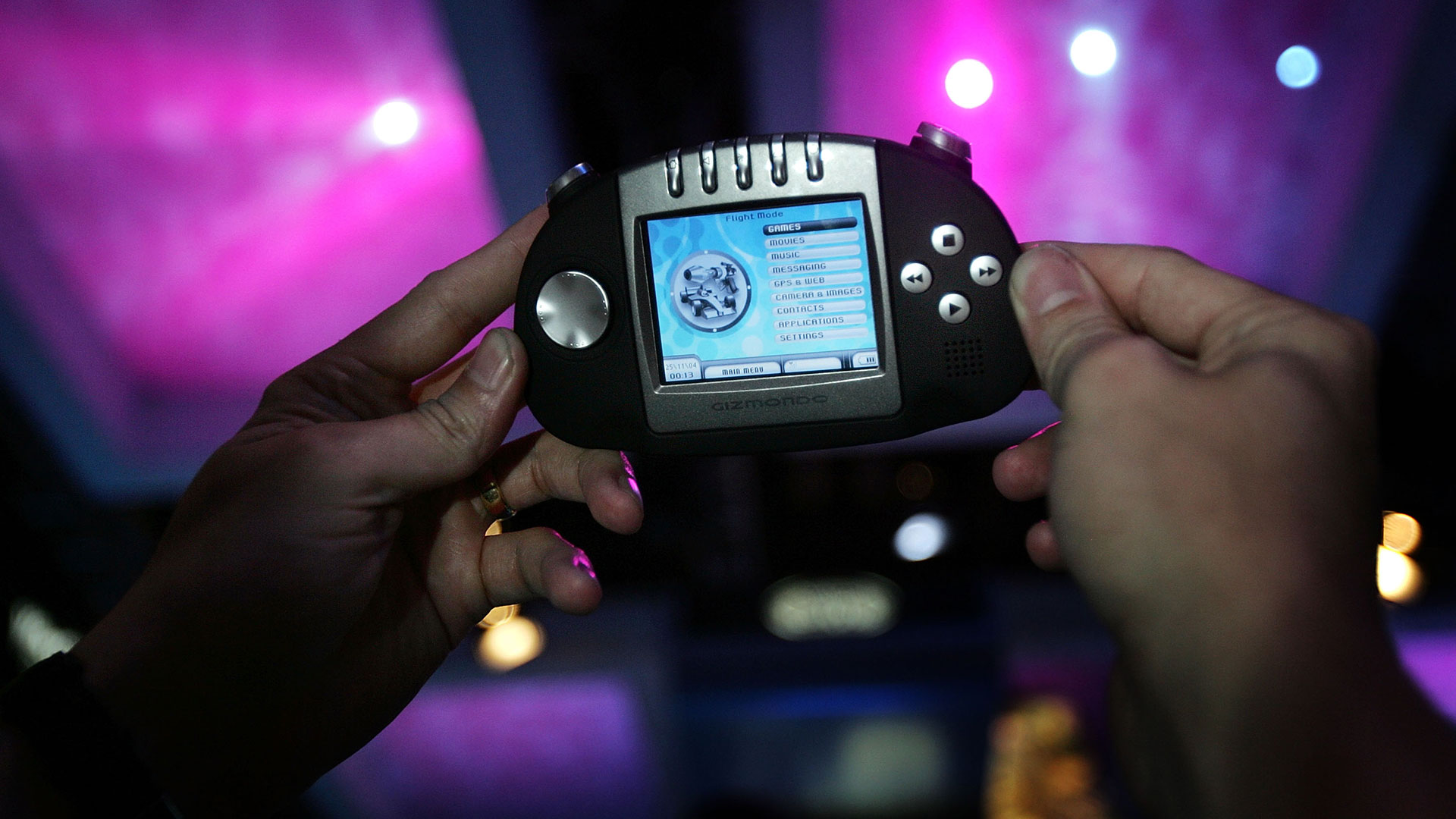

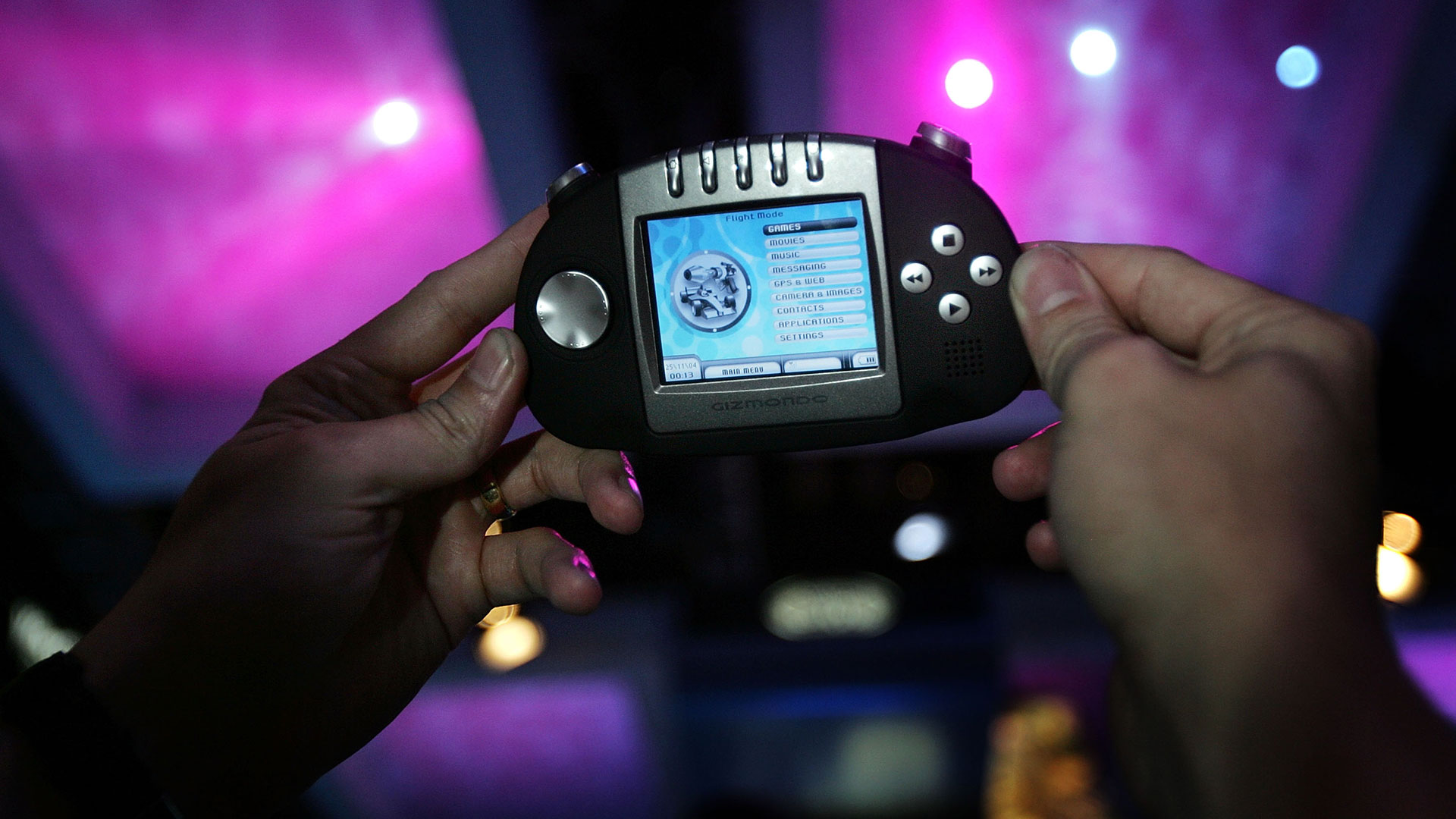

The cheapest things in the entire store were the flimsy Gizmondo handheld gaming consoles themselves. When you looked closely, the store was s smokescreen—like the Isis Models themselves—to conceal the real purpose of Gizmondo: extracting money from potential investors.

Eriksson was a showman, and he knew how to make an entrance. At one party, he and his crew—Eriksson in a red Ferrari Enzo, Peter Uf (another Gizmondo executive, and another former member of the Uppsala Mafia) in a black Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, and London club promoter Bally Singh in Eriksson’s black Enzo—rolled up to the VIP entrance and began smoking their tires in front of the packed store. “It was like one of those car-chase movies, and they all just sped up and screeched to a halt in the middle of Regent Street,” laughs Horgan-Wallace in recollection.

She paints a picture of Freer and Eriksson wooing investors with the same techniques they used to romance women. Their parties were spectacularly expensive affairs, and they hired Singh to attract the hottest talent and eye candy. Sting and Danii Minogue played at their parties; they hired Pharrell and Busta Rhymes to rap about their console.

“I saw it all the time—you send a potential investor down to that flagship store and they’re gonna be putty in your hands,” Horgan-Wallace continues, telling the story of a particular evening when Stefan entertained some visiting German associates. “He’d bring them down to the shop and have meetings downstairs, with us glamorous, beautiful jollybirds walking around, getting them drinks. Carl did it in a more sophisticated manner, more businesslike. We’d make ourselves friendly, sitting on laps, that type of thing—but never too serious; not like it was a whorehouse or anything. Some of the girls were meeting guys with massive amounts of money, and a lot of these girls didn’t know what they were doing, so the guys would go in for the kill. Some, of course, took advantage of the parties…and the girls.”

A recurring theme in the tale of Gizmondo is the employment of glamour in the original sense: as a spell cast, dazzling possible investors with the glimmer of diamonds, the implied ringing of a cash register and the supple sheen of a model’s thigh. And making them willing puppets in the process. “This is what their trick was: to have all the girls, have the drinks, have the riches. And these investors are businessmen who don’t get out of the office much, and suddenly they’re surrounded by this amazing sort of movie star lifestyle, with girls who they couldn’t imagine talking to, let alone having drinks with. If men are shown a lifestyle that they can’t achieve by themselves then I think they’re gonna be persuaded, definitely.” These investors clearly weren’t just buying into a company’s balance sheet, they were buying into a lifestyle that they’d only ever seen from afar, from across the vast chasm of the velvet rope.

For the one system both Eriksson and Freer mastered was that of currency—a one-way street in their world, where cash flowed in but never flowed out. They would pay everyone, even their closest allies, in Gizmondo paper stocks, never cash. And no one cared as long as the Gizmondo stock soared—their associates were becoming obscenely wealthy as the stock jumped from four cents per share to a peak of $32.50 per share in January of 2005. When one of their underlings performed well, they never paid them a bonus but rather rewarded them with company cars. Or better yet, a Rolex watch; bankruptcy papers show Gizmondo spent about $650,000 on watches as gifts. For many of the crew who came from a street level criminality, the exchange was lucrative, at least at first. Soon they were all flossing like millionaires in AMGs, Audemars Piguets shining on their wrists.

Both Freer and Eriksson had a dizzying obsession with expensive, usually diamond-encrusted timepieces. Eriksson’s collection alone was valued between $800,000 to $1.3 million. Freer custom-built a hidden case that would rise from his bedroom bureau with the press of a button, exposing about 30 watches and automatically winding them simultaneously. Of course, the cars were company cars, merely loans. So while there was the illusion of fair exchange, there really was no exchange at all: Eriksson and Freer got diehard loyalty and free labor in exchange for Gizmondo stock, while their underlings were allowed to drive outrageous automobiles that they nonetheless didn’t own. Models, supercars, diamond watches, paper stocks, parties: these were the currencies in Gizmondo nation, and everyone thought of themselves as fucking rich.

“I did feel guilty sometimes when I used to see investors come into the store, because even though it seemed legitimate I just had a feeling it might be dodgy dealings,” admits Horgan-Wallace in a moment of forthrightness. “I just felt a bit guilty about the guys that were investing lots of money. I remember saying that to one of the girls once and she was like, ‘Don’t be ridiculous! That’s not the case!’ But I always suspected, because it was just too much money for normal business. I don’t think even Playstation would put on parties like that for their PSP, and they’re Sony! And they had a better console!” So while the stock rose and rose, and the actual Gizmondo console remained little more than a malfunctioning prototype surrounded by empty press releases—though releases that were promising exciting, emerging handheld tech like Bluetooth, a 1.3-megapixel camera, GPS, and SMS messaging, although those things never materialized—no one bothered to look around, to notice the discrepancy between their own huge investments and the underwhelming product

No one bothered to ask: Where exactly are these hundreds of millions of dollars being invested?