Midmorning, heading north on the I-405 from Los Angeles International Airport, I am stuck in a traffic jam. A sea of vehicles of every make surrounds me: long-haul semis, boxy sedans, Denalis with tinted windows, Priuses with Uber stickers, black town cars, landscaping trucks, and the occasional zesty convertible.

My own rented black GMC Terrain is one of those nondescript compact SUVs that automakers stamp out with all the cookie-cutter variation of a Ford Model T. If parked in a crowded lot, I would fail to pick out my rental without clicking its key fob to trigger the lights.

(Here is the author’s note to the new book FASTER, which tells the true story of how an American heiress and outcast Jewish driver took on the Third Reich’s Silver Arrows at the brink of WWII, by New York Times bestselling author Neal Bascomb, available at your local bookstore and on Amazon. This excerpt has been lightly edited for style. -KC)

None of us is getting anywhere fast. Ten minutes pass at a standstill. Then 20. According to Google Maps, I have another 58 miles—or one hour, 52 minutes—to go until I reach Oxnard. The line of my route on the screen map looks an ugly red. Surely they will wait for me before they ship the Delahaye 145 race car off to London to sit behind a velvet rope in the Victoria & Albert Museum. I try not to pound the steering wheel in frustration.

The bottleneck ahead finally loosens. Once I veer off onto the I-10 toward Santa Monica, the stop-and-go traffic becomes mostly go. Then I am cruising north on the Pacific Coast Highway. In the distance, there are mostly vistas of ocean and wildflower-covered hillsides. I might make it after all.

My GMC is comfortable, but unexciting—a rental car obligation. Retractable seats with good lumbar support. Automatic transmission. Apple CarPlay to listen to my latest Spotify favorite, the Lumineers. Past Malibu, I battle with the electronic windows, unable to convince them to remain half-open. Instead, I seal myself into the air-conditioned cocoon. No salty breezes for me. At stoplights, the engine shuts off to save gas. It does not ask me for permission.

Halfway there I take a call from my wife in Seattle. She cannot even tell I’m driving. Whatever churns underneath the hood, it is quiet, reasonable, and unflappable, all worthy qualities in a vehicle meant to get one safely from point A to point B.

A very different car is being readied for me in Oxnard. It is a reward—and capstone—after two years of investigation into its long-forgotten history.

There was a period, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, when the Delahaye 145 was one of the most noted Grand Prix race cars in the world. Its exploits had equal billing to news stories of peace coming undone in Europe. Huge crowds assembled to watch it compete or to glimpse its shiny V12 engine up close at motor shows.

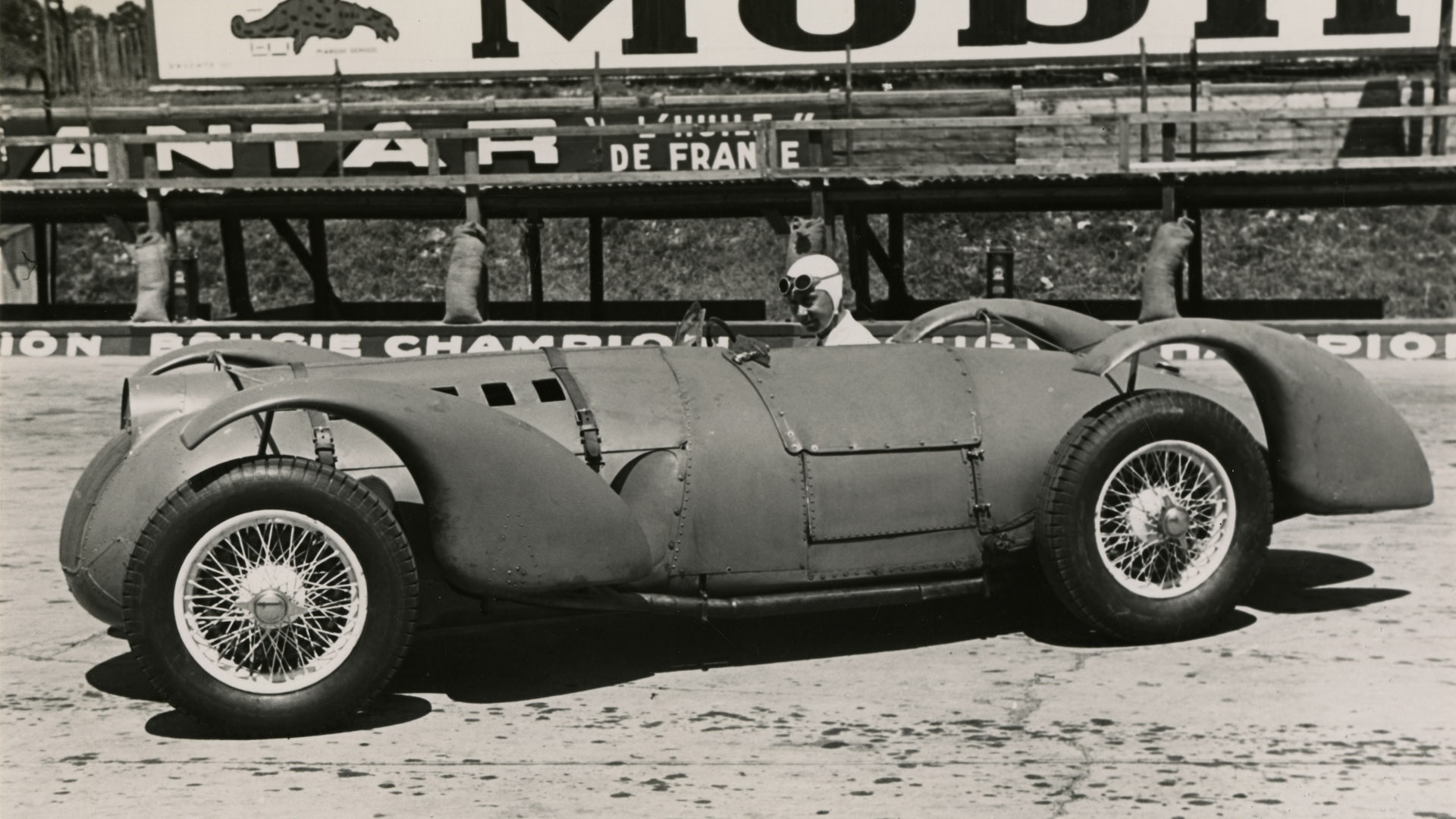

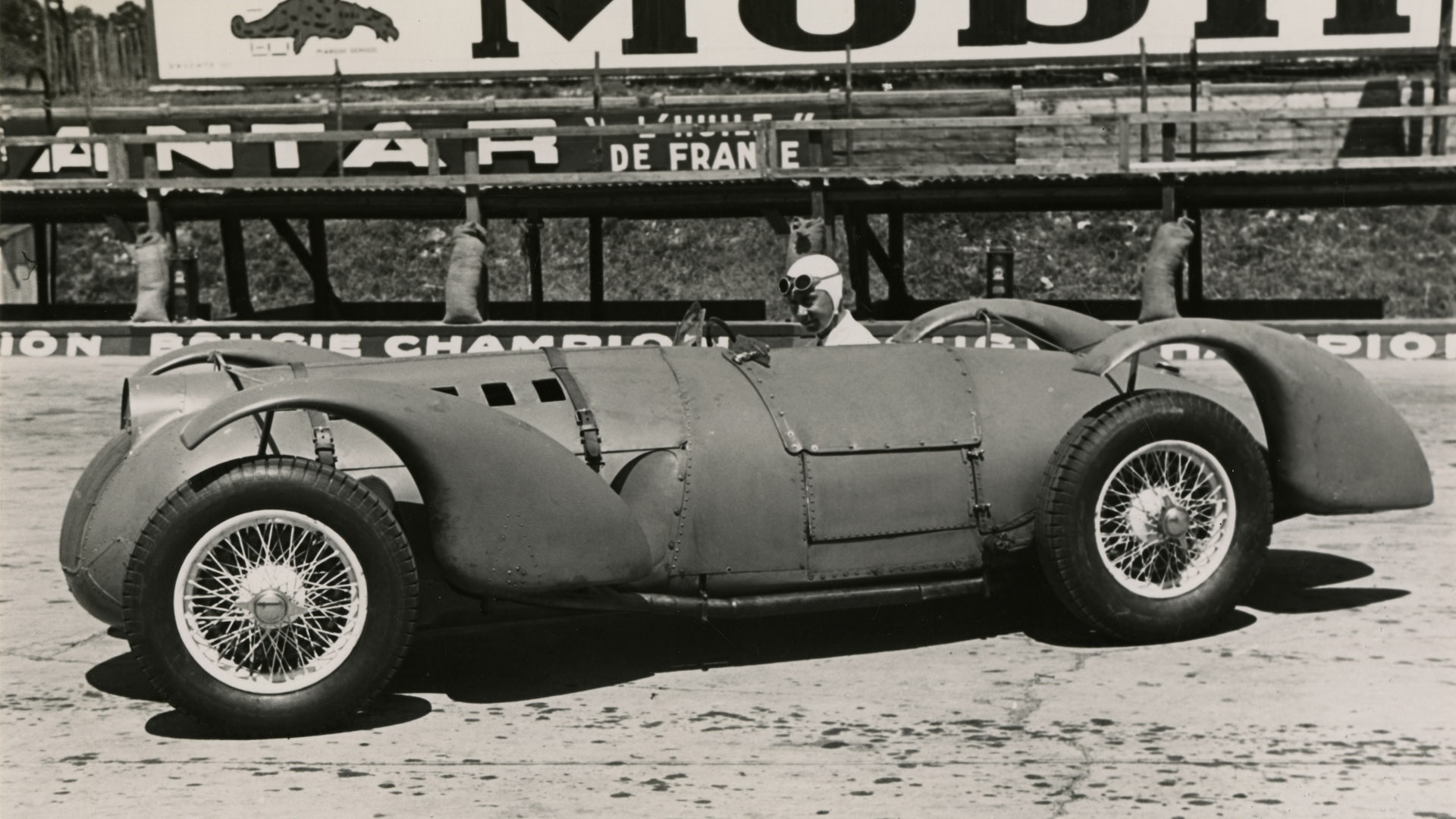

When it first appeared at Montlhéry, an autodrome in France, many thought its design peculiar. One critic likened it to a “praying mantis” rather than a machine built for speed. After the Delahaye smashed records on the closed oval circuit, sought the “Million Franc” prize, and dared to be “The Car That Beat Hitler,” the naysayers became adoring admirers. Its owner, its designer and builder, and the driver who often risked death pushing the Delahaye to the limit were heralded as national heroes.

Its story began in 1933, when the leader of the new Third Reich made reigning over the Grand Prix one of his first missions. His Silver Arrow race cars, piloted by the ruthlessly indefatigable champion Rudi Caracciola and the blond-haired, blue-eyed poster boy Bernd Rosemeyer, stood for more than sporting prowess: they represented the master race conquering the rest of the world. “A Mercedes-Benz victory is a German victory,” heralded the Nazi propaganda machine. Hitler aimed to use their success to inspire hundreds of thousands of young men to enlist in the ranks of a motorized army, which its automobile firms, now transitioning into massive industrial machines, would help bring into being.

After years of unchecked German triumph, a woman called Lucy O’Reilly Schell decided that something must be done, so she launched her own Grand Prix racing team. A dazzlingly fine driver in her own right and the only child of a well-heeled American entrepreneur, she had cash to spend, reasons of her own to challenge the Germans, and the will to claim her place in a world dominated by men.

For a car, she chose the most unlikely of manufacturers: Delahaye. Managed by Charles Weiffenbach, the old French firm was known for producing sturdy, staid vehicles, mostly trucks. Racing was a path to save the small company. For a driver, Lucy recruited René Dreyfus; once a meteoric up-and-comer, he had been excluded from competing on the best teams, with the best cars, because of his Jewish heritage. Triumph over the Nazis promised redemption for all of them.

My journey to uncover this tale of a team of strivers took me in many directions. Unlike the prewar stories of such sports giants as Jesse Owens, Joe Louis, or that “crooked-leg racehorse named Seabiscuit,” time had largely erased from memory the endeavors of Lucy, René, Charles, and the Delahaye 145. No writer had devoted a book solely to the subject.

At first, I sank myself into libraries like the marvelous Revs Institute in Naples, Florida. This was my first foray into automotive history, and the sheer volume of contemporaneous journals and magazines devoted to the Grand Prix—in multiple languages—stunned me.

Day after day, I paged through thousands of pages, rooting out pieces of the saga. The Daimler-Benz Archives in Stuttgart and the National Library of France in Paris proved equally helpful.

I quickly learned that information on classic cars—and their drivers—is deeply cherished but often held closely by clubs and private collectors. Diligence and a little bit of persuasion gained me access to scholarly treasures held inside a sprawling French farmhouse, a cluttered Seattle garage, and a storybook English manor, among other places. The family of René Dreyfus shed a lot of light as well.

It is one thing to study detailed course maps of the significant races in this history. It is another to walk or drive them. La Turbie outside Nice. The Nürburgring in the Eifel Mountains. Montlhéry south of Paris. Monaco through the streets of Monte Carlo. Pau on the edge of the Pyrenees separating Spain and France. I wanted to know every hairpin, every straight, every rise and fall.

Throughout my research, I visited numerous car museums across America and Europe, wandering among the collections of Alfa Romeos, Bugattis, Maseratis, Delahayes, Talbots, Ferraris, Mercedes, Peugeots, and Fords. Polished to a sheen, these cars looked like works of art. And they were immobile, surrounded by walls, their purpose—to go fast—thwarted now.

I wanted—and needed—to experience a sliver of what the heroes of this story had experienced in the cars they raced, most of all the Delahaye. In response to repeated requests, Richard Adatto, a board member and curator of sorts for the Mullin Automotive Museum, invited me for a drive. The museum, in Oxnard, California, was founded by American multimillionaire and collector Peter Mullin, who owned all but one of the four 145s.

I finally reach the museum parking lot. I turn into it and come to a quick stop. Just in time.

Someone calls my name as I climb out of my GMC. It is Richard, waving me over. Richard has a measured, no-nonsense demeanor that only occasionally is broken by an impish smile. In his 60s, and a builder by profession, he is also an expert on prewar French cars. He leads me over to a boxy white warehouse opposite the museum.

The tapered tail of a car sticks halfway out of the warehouse door. The Delahaye 145.

The many black-and-white photographs I have seen of the race car do it little justice. Painted a sky blue, the two-seater stands long, lean, and low, appearing altogether like a tiger crouched in anticipation of a leap. It is over eighty years old yet somehow looks futuristic, particularly with the swooping lines of its mudguards hovering over tires that look too narrow to handle much speed.

After opening the toy-sized door, Richard folds himself into the driver’s seat. Nate, the museum’s cheerful mechanic, leads him through the ignition process. Pull this. Turn that. Press this. The engine fires up, smoke billows from the twin exhausts, and the thunder of the engine nearly deafens me.

Several years have passed since the 4.5-liter V12 engine was last started, yet after Nate performed some routine checks and replaced its twenty-four spark plugs before my arrival, the Delahaye rumbled awake with barely any hesitation.

Richard and Nate take the Delahaye on a short round of the parking lot to make sure everything is okay; then the car is winched inside a trailer and secured into place. In a separate vehicle, Richard and I follow the trailer away from the museum and, after fifteen minutes, deep into the lemon groves outside Oxnard.

The empty roads that thread through the groves are the perfect place to let the Delahaye run free. It does not like to stop and start, nor to putter away in traffic. It is a race car, after all.

The trailer halts on the gravel shoulder of a side road, and down the ramp comes the Delahaye. Richard is first into the open cockpit, shoehorning himself into the driver’s seat on the right side of the car. Nate opens the door on the passenger side for me.

Despite my many entreaties to drive the Delahaye myself, I was denied—and not without reason. The 145 was worth many millions of dollars, and Peter Mullin did not need an uninsured amateur seizing up its engine or pitching it into a tree. Anyway, given how tightly Richard and I are pressed together in the narrow two-seater, there is little distinction between driver and passenger.

Nate hitches a belt around my waist, a likely useless safety feature that René Dreyfus did not benefit from during his days piloting the Delahaye. Then, as today, one drove with neither a roll bar nor a crash helmet.

The engine growls at idle, uneasy. Looming over the Santa Monica Mountains, a bright sun shines down on us. The lemons hanging from the trees look as big as grapefruit. The smell of oil pervades the air. My left hand grips the cold steel of a handle secured on the dash. My senses feel sharper than usual.

Richard steps on the clutch and shifts into first gear. We roll off the gravel onto the road and make a 180-degree turn to point in the direction of a long straight. At five feet, seven inches, I am the same height that René was. My eyes barely rise over the long hood. There is no windscreen. I am seated low and at a slight angle, my legs stretched out in the footwell. For some reason, I can’t shake the impression that I am riding in a mechanized sled, such is my body position and my proximity to the ground. When I reach out over the door, my fingertips nearly brush the asphalt.

Without a hint of warning, Richard vaults down the road, engine wailing as he shifts from first to second, then third. We move faster and faster, the wind sweeping back my hair. I turn to Richard. He holds the big steering wheel at ten and two, making slight, but constant, adjustments. There is that impish smile. He is loving this.

I am scared. My grip tightens on the handle. The Delahaye does not feel stable. It fights to hold a straight line. A deep ditch borders the road. A plunge there would surely be the end of things. I have a family. Young children. Ahead approaches a sharp turn.

Richard neither brakes nor eases on the throttle. My feet press pedals that do not exist. Richard swings the wheel counterclockwise, and the tires clip the gravel edge of the road as we make the left turn. The Delahaye hugs tight to the ground as we make the turn. Coming out of it, Richard presses on the gas, then shifts gears again. The speedometer needle swings sharply. We are now devouring an uphill climb. The engine pitches to a high scream. Quickly we enter another turn, this one to the right. Again the Delahaye clings to the road. We enter a long undulating straight.

A quick upshift. The Delahaye jolts ahead, faster than before, past the rows of lemon trees. Any fear fades away. The wind presses my hair back. It ripples my cheeks. The acceleration forces my upper body against the seat. The engine rises to an ear-splitting howl and throbs all around me, alive. We rocket forward. I feel every dip and hump in the road, but am not jarred; it is like I am welded with the Delahaye. It is the same with every shift of the gears, every tap on the brakes. Time evaporates. The world distills into the band of pavement ahead and the surrounding rush of wind and noise.

“Remarkable,” I whisper. “Remarkable.”

We summit a small hill, and it almost feels like we are flying.

All of a sudden, Richard slows. We have come out of the groves and have reached a highway intersection. Trucks shudder past. From my perspective inside the low-slung Delahaye, they look like giants. With a break in the traffic, Richard turns onto the highway.

After some grinding of the ancient gears, he quickly hits fourth. We race even faster than before, engine yawping, as we almost leap onto the tail of a boxy sedan ahead. The acceleration is incredible. Then a quick jab of the steering wheel, and we head back into the groves. A farmer among the rows stares at the Delahaye, mouth agape. Another lightning straight, and we return to where we started beside the trailer.

Richard cuts the engine. The Delahaye stills. I perform some yoga moves to unfold myself from the seat and stand outside the car. I feel the ground stable under my feet, rather like when you step off a boat onto land.

Richard tells me that we barely broke 75 mph. I am stunned, not only because it felt like we were moving much faster but also because that is almost half the speed René Dreyfus would have run the Delahaye during the Grand Prix. Half.

A bicyclist pulls up beside us and stares at the car, not quite sure what to make of it. He asks Richard and Nate a bunch of questions. He is truly spellbound.

While they chatter, I climb into the driver’s seat of the motionless Delahaye. I grip the steering wheel and the gearshift. I rest my feet on the clutch and the accelerator. For a moment, I am racing through the lemon groves again, the sun hot on my face, the wind screaming in my ears. More than ever, I appreciate how remarkable a car the 145 was in its glory days, the force of will that Lucy Schell showed in seeing it built, and the incredible skill and guts that René must have had to pilot it against the titans funded by the Third Reich.

Enzo Ferrari called racing “this life of fearful joys.” I never quite understood his words until that afternoon.

To read the history of this remarkable Delahaye and the people who raced it, FASTER is available at your local bookstore and on Amazon.

Neal Bascomb is the national award-winning and New York Times best-selling author of The Winter Fortress, Hunting Eichmann, and The Perfect Mile, among others. A former journalist based in London and Paris, he now lives in Philadelphia.