Experiencing Le Mans For the Very First Time, and Not Caring

An Unenthusiast special report. Well, maybe “special” is the wrong term.

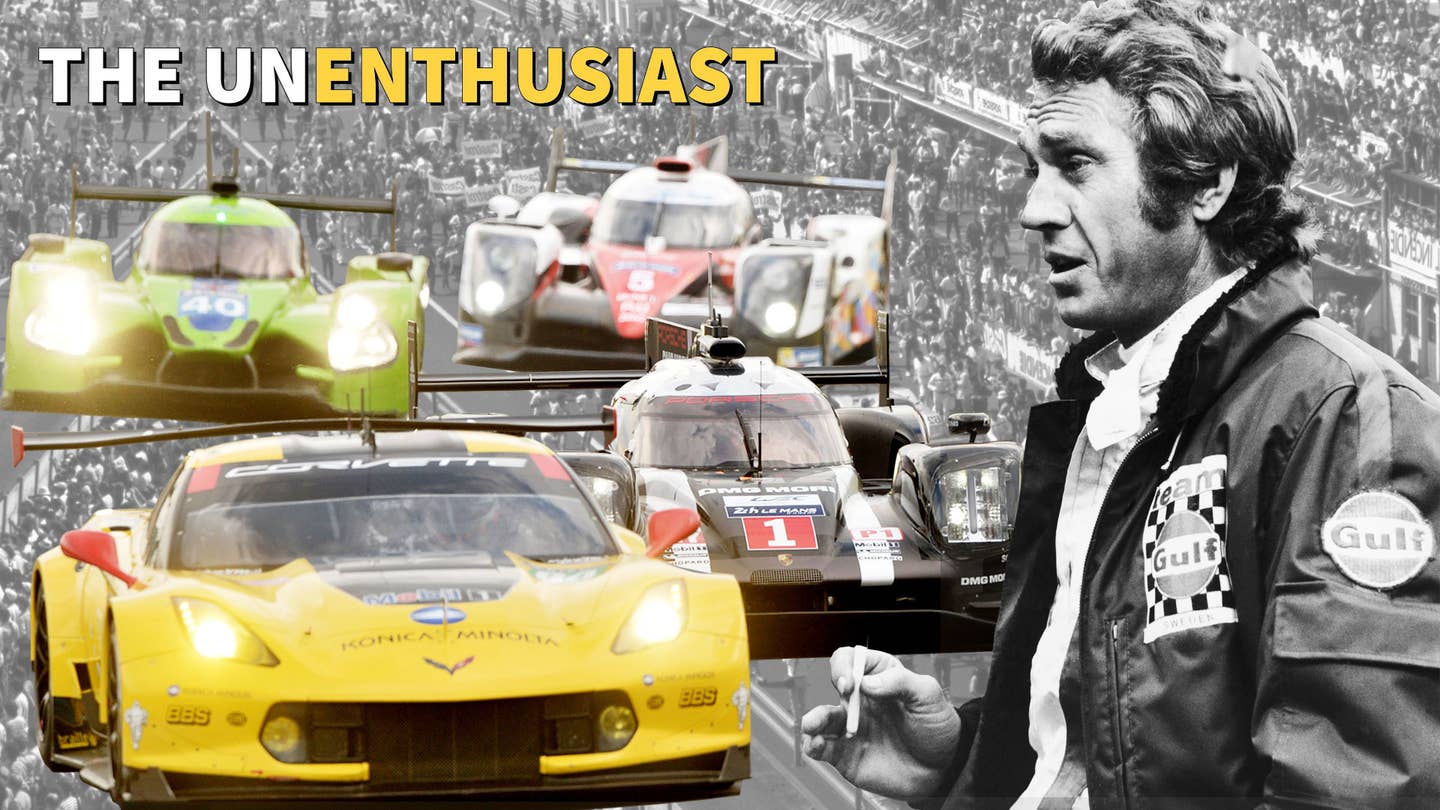

Never in my life, not for one second, had I thought about the 24-hour race at Le Mans. I’d not watched any videos or read a single race result. Not only did I have no rooting interest, I knew nothing about the track (other than the fact that it’s somewhere in France), or the history of the teams, or about endurance racing in general. I’d seen the Steve McQueen movie, but had basically watched it for cigarette-smoking tips, even though I don’t smoke cigarettes. As far as I was concerned, the race was going to be Dastardly and Muttly puttering around the French countryside in a propeller jalopy.

Now I’ve been here for a few days, and I still don’t care. However, I’ve learned quite a bit, mostly by listening to other journalists blather. There are four classes of cars at Le Mans, which race all night to get lucky. One, called ProJo Superior Class, is made up of teams owned by very rich auto manufacturers: Porsche, Audi, and, somewhat surprisingly, Toyota. These cars, in the only factoid I’ve learned that gives me even the slightest chubby, are hybrids, as dictated by the Le Mans governing board, a group of enormous holographic heads who sit in a cylindrical chamber and pass down judgment. I took a pit walk this morning to look at the Toyota car, which had wings and teeth. If I could have taken this car home with me, I would have. It looked like what my Prius will eventually evolve into, like a Pokemon.

Then there are two classes of cars that are, for lack of a better description, Rich Guy Toys. A fourth class, the most interesting one, called Cars That Look Like Actual Cars, features a very powerful asshole Corvette and a Ford GT, which has made a triumphant return, like Elvis in Vegas, to the place where it gained glory 50 years ago, when men were men and engines ran on peasant blood and Ralph Nader hadn’t yet ruined everything. It is, naturally, the sentimental favorite.

LeMans, like Indianapolis, runs on nostalgia, particularly for 1966, but also for every other year, including the one we’re in now. Everyone here goes on and on about “racing heritage,” like it’s something that actually exists. There’s nostalgia for this year’s race, and it hasn’t even started yet. The era of planet-destroying combustion engines is coming to an end, so we’d best celebrate them now before they go away forever.

As far as I can tell, there are three general types of people at Le Mans: those who are actually here for work, all of whom are stunningly handsome and wear clean company Polos even though they are toiling in grease pits day and night; slack-jawed hillbillies who live in parking-lot tents, possibly year-round; and rich toffs who hang out in luxury lounges, eating parfaits and listening to shitty DJ music. That actually sums up Europe in general, but everything is accentuated here because it’s concentrated around 8-plus miles of asphalt. The track itself is only partially a track, the rest of it comprised by what appears to be historic airport access roads, all of it very narrow, like a Parisian’s hips.

There is a “fan zone.” Though I’ve heard rumors of live burlesque shows, mostly it appears to be comprised of drunken British men moaning at the poor performance of their soccer team in the Euro cup, surrounded by promotional tents for Ferrari and Honda and Ford. It’s like Harry Potter World, except the butter beer is actual beer, and there’s no magic, unless you consider race cars magical, which apparently people do.

There are millions, or at least thousands, of guys worldwide who would be happy to die tomorrow if they got to drive around la Sarthe (French for “The Sarthe”) for real one time, instead of just in Gran Turismo. I don’t play Gran Turismo, I play Words With Friends and a nerdy game involving baseball statistics. But I got to drive around the Le Mans track anyway, because I am an automotive journalist, the world’s oldest profession.

There were ten of us, two per car. The cars were brand new Audi S4s that contained, as another journalist said, “single-turbo hot-V three-liters,” whatever the fuck that means. Regardless, they were fast. I got a helmet and strapped it on tight.

Here were the ground rules:

- No passing

- When they say go, you gotta go

- No passing

- Please keep distance between cars

- You might miss a brake point (which didn’t sound like a ground rule to me, but I wasn’t in charge)

- Beware of flying rocks

- Try not to crack the windshield or mess up the body paint

- After the first lap, “do a fast Chinese fire drill to switch drivers because we have a limited amount of time”

At that point, I surmised that the hour of my death was at hand. Those would be the last ground rules I’d ever hear. Briefly, I thought about quitting. But I screwed my courage to the sticking post, because I needed to get paid.

My partner was a nice guy named Jeff, a gruff veteran of the race wars, who writes for AutoWeek.

“I’m not a very good driver,” he told me.

“Maybe I should go first,” I said.

I got behind the wheel. Jeff and I had been assigned car number 5, out of five. We were the last seed, the rear-guard, the Moron Class. I drove into the queue. A very stern German man (is there any other kind?) told me to roll down the window.

“It will be at least 20 minutes until you start,” he said.

“OK,” I said.

“We had a crash,” he said.

“Great.”

“You were informed about the driver switch?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“It must be fast,” he said. “What we are doing is exceptional.”

“Is it OK to drive hot laps with wrist tendinitis?” I asked.

He walked away.

Suddenly, the schedule changed, and the cars started to move, and then I was barreling under the Dunlop bridge at 220 km/h. Jeff started making idle conversation. I threw up a hand.

“Gotta focus!” I said.

I was going to use all the skills I’d learned at the Jaguar Performance Driving Academy a few years ago. And, I must say, I did pretty well. I never fell far behind. Admittedly, it was auto racing for dummies. We consistently braked 150 meters earlier than necessary, which made hitting apexes quite easy. The paddle shifters had been disabled to guard against journos who think they know how to drive. I ripped around turns, handled the chicanes OK, breathed, kept focus. The banners passed overhead like they do on the video game that I never play.

And then, after eight-plus miles and three-and-a-half minutes, it was over.

“Move move move!” I heard.

Jeff and I dashed out of the car and switched seats. The line moved again. He was right. He wasn’t a very good driver.

Almost immediately, I started to retch.

“Hang in there, kid”! Jeff said, and he slapped my leg.

“Keep both hands on the wheel, dammit!” I said.

For the next four minutes, I gagged and moaned and sweated around my gills. But I endured. Using my yoga skills, I observed my breath, and tried to keep my eyes straight ahead. Gentle Reader, I didn’t barf into my helmet one time!

As the fantasy, or the nightmare, ended, I staggered out of the car, greener than the bribe money that Ford paid this year’s governing body.

“You got guts,” Jeff said to me, even though I have none. “You knew what you were getting into. It’s like getting on a roller coaster. The first time you’re a dumbass. The second time, you know.”

“No guts, no glory,” I said.

Another journo bounded up to me like a puppy.

“That was amazing!” he said.

“Eh,” I said.

Hooray, I’d driven around LeMans, checking yet another item of my cousin MichaeI's—an actual automotive enthusiast—bucket list. I felt a buzz for hours afterward, but it wasn’t a pleasant buzz like I get after sex or a bong hit or cheese. It was something else, an uneasy feeling of transgression, like I’d witnessed a murder but hadn’t told anyone.

Later, another journalist asked, “what did you think of the track?”

“It was very long,” I said.

“What was the surface like?”

“It was a road,” I said. “With some turns.”

He was quickly getting frustrated with me.

“But do you maybe now have an appreciation of what it might be like to drive it at night with all kinds of different cars on it, what it might be like to suddenly have to swerve and avoid a car even if it’s raining?”

“Not really,” I said.

Soon after, the real drivers took the stage. It was time for qualifying, or, as one of my colleagues obnoxiously called them, “Quallies.” They could have been called Quaaludes for all I cared. That’s what I needed the second I stepped onto the bleachers. Cars of all shapes and sizes were screaming around the track, lights on because a horrible thunderstorm was looming, as gobs of pallid old Frenchmen stared at all this as though it mattered. My ears immediately began to bleed. I dashed downstairs and found one of the event ladies who was being paid to be nice to me for the week.

“Do you have earplugs?” I asked, desperately.

They wouldn’t be available until tomorrow.

I had to get away immediately. Two colleagues were getting into a car to take them back to where we were staying. I climbed into the front seat to escape the noise, the stench, and the aura of people for whom the return of the Ford GT had the same significance as Christ emerging from the tomb.

Sonofabitch, I thought. I really am in the wrong line of work.